by Nicholas Borroz

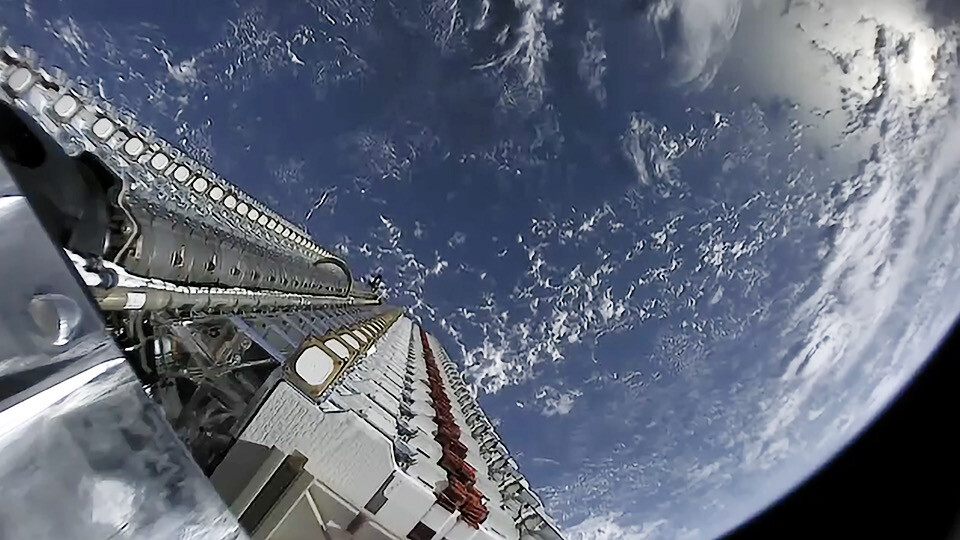

Credits: Official SpaceX Photos, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The term “space insurance” often refers to first-party insurance that covers pre-launch, launch, initial operations in orbit, and longer lifetimes in orbit. There are two main reasons why space firms buy insurance. The first is for “refund” purposes – it allows them to recover costs that led up to an accident, repay financiers, and exit a business entirely. The second is for “reflight” purposes – it recovers costs associated with a particular mission and allows the firm to try again. Buying insurance entails understanding what costs are covered and the likelihood of an accident. Based on this, insurers charge a “premium” to provide coverage – essentially a percentage of the total amount they will pay customers if an accident occurs.

Insurers want to know a great level of detail about the insured systems, including any modifications made to those systems when preparing for launch (as often happens); they do not tolerate “overinsuring”, which incentivizes accidents, or “underinsuring”, which allows firms to pay less in premiums than they otherwise would. Payout disputes can arise over whether a system’s details were accurately represented to insurers.

It is also worth noting that there are other costs associated with buying insurance besides premiums. One notable example relates to the extensive exchange of technical information that insurers often require: space firms must stand up to compliance programs to ensure the information exchanges do not violate relevant export control regulations.

“Pre-launch” insurance essentially regards transporting and handling cargo, and insurers in other industries often provide this. In later stages, though, insurance is provided by insurers who specialize in space. The most typical space insurance coverage is a package deal, comprising launch coverage plus coverage for the first year in orbit; this is because the greatest risk of on-orbit failure for satellites occurs during their first year in orbit.

Third-party liability insurance

“Space insurance” also often refers to third-party liability insurance, a major impetus for which is governments’ responsibility for objects launched to space. Besides insuring themselves against accidents, space firms also buy insurance to pay for damages they may cause others – someone affected by falling debris, for instance. Under international law, governments are responsible for damages resulting from space activities occurring under their jurisdiction. Governments therefore often require firms to buy third-party insurance, because doing so minimizes possible government expenses. Insurance requirements are often capped at a certain value, after which point governments take on responsibility for paying damages.

The most typical space insurance coverage is a package deal, comprising launch coverage plus coverage for the first year in orbit; this is because the greatest risk of on-orbit failure for satellites occurs during their first year in orbit.

Governments cap insurance requirements at certain amounts so insurance does not become prohibitively expensive to space firms and stifle industry growth. Governments try to strike a balance between requiring firms to be responsible for some payments, but not so many payments that the firms decide working in space is too costly.

The risk manager-broker relationship

Risk managers in space firms typically buy insurance via brokers, who bring risk opportunities to insurers and their underwriters. Risk managers help space firms assess how to spend resources to manage risk. They are usually responsible for buying insurance (in smaller firms, this role may fall to other employees). Risk managers usually buy insurance indirectly via brokers, who in turn compete to sell brokering services to risk managers. Brokers maintain a network of relations with insurers (the firms providing insurance). Risk managers inform the brokers they seek to buy insurance, and the brokers bring those opportunities to the insurers. Underwriters are responsible for calculating the risk and determining a premium that insurers charge; underwriters may work inside insurance firms or be contracted out.

It is important to notice that, though space firms are the ones buying insurance, the dynamic is often one of the brokers “selling risk” to insurers – brokers try to give insurers enough understanding about and confidence in the system so they feel comfortable insuring it. Brokers typically start shopping for insurance about two years before launch.

A volatile and small market

Space insurance is a volatile market – there are relatively few insurers, and a single large accident can shrink global capacity and dramatically affect prices. There are fewer insurers for space than for many other industries – approximately 30 to 40 “markets” exist worldwide. The total capacity of space-dedicated insurance is estimated to be in the range of $500 million to $1 billion. Given that large GEO sats cost hundreds of millions of dollars, it is easy to understand why premiums fluctuate wildly; when a large loss occurs, the market quickly “hardens”, meaning there is less available insurance and premiums rise significantly.

Though space firms are the ones buying insurance, the dynamic is often one of brokers “selling risk” to insurers.

Another effect of the small market size is single insurers rarely provide total coverage; almost always, groups of insurers provide coverage. Brokers cobble together coverage from many insurers, trying to harmonize terms and premiums. Even if a single insurer could provide total coverage, it is unlikely to do so because it will want to diversify risk exposure over a portfolio; it will spread its exposure so that it feels confident that its collected premiums can cover an expected number of payouts it may need to make.

One reason why there are so few space-dedicated insurers is barriers to entry are high. Larger insurers are better able to diversify their risk holdings so that they are less likely to be overly exposed and suffer a major business catastrophe.

Interestingly, “market” is an ambiguous term often used by professionals in the insurance industry. It sometimes refers to one firm. At other times, it refers to a syndicate of firms. At still other times, it refers to a national community of insurers. And sometimes it refers to groups of insurers who relate to each other in some other way.

Insurance and Re-Insurance: what is the difference?

In space insurance, there is little specialization in insurance and re-insurance, given the limited size of the market. Insurers are the entities insuring space firms, whereas reinsurers are the entities insuring the insurers. In larger insurance markets serving other industries, insurance firms often specialize in either insurance or reinsurance. But this is not the case in space, due mostly to the fact that there is a limited number of insurance providers. In space, rather, firms regularly switch back and forth between insurer and reinsurer roles.

Governments sometimes impose national insurance requirements; space firms are required to buy a certain amount of insurance from local providers. This requirement may exist even if local insurers do not have enough capacity to provide insurance. In such cases, the local insurers act as the primary insurers, but they then heavily reinsure themselves with insurers in other markets.

GEO vs. LEO sats insurance market

Space insurance has traditionally been for large GEO sats; insurers are less inclined to insure small LEO sats. Space insurance’s emergence depended on the development of the GEO sat industry. GEO sats have been insurers’ “bread and butter” because they are so large and expensive that operators feel compelled to insure them. But nowadays the majority of satellites being launched are going to LEO, and insurers are less inclined to insure them for three reasons: 1) LEO small sats have less heritage, which makes their risk profiles difficult to assess; 2) LEO sat operators pay smaller premiums than GEO sat operators because of LEO sats’ lower value; and 3) LEO sats often belong to constellations, which makes it difficult to assess mission failure.

LEO satellite owners and operators, for their part, are less interested in insuring satellites. Constellation firms tend to “bake in” certain levels of failure into their strategies. It is common for them to launch spare satellites, for instance. Insurers have yet to devise insurance schemes for which there is widespread demand amongst LEO sat operators.

One reason why there are so few space-dedicated insurers is barriers to entry are high.

Traditionally, sat insurance is based on assets rather than revenue. Given constellations include spares, there is little incentive to insure satellites (though asset-based insurance may develop as insurers and operators identify critical aspects of constellations that need coverage). And many constellations are still in the process of establishing revenue streams, so it is unclear what revenue-based insurance schemes should look like. Constellation firms still often buy insurance for launches, though. This is because a certain amount of satellite attrition in space is built into business plans, but not the loss of several satellites at once that are being launched on the same vehicle.

A major change on the horizon for LEO space insurance relates to space debris – governments may address space debris with new insurance requirements. Space debris is a high-profile issue, so high that even people outside the space industry are aware of it. Many governments are now contemplating imposing debris-related insurance requirements on firms. A major challenge will be determining the appropriate amount of insurance to require; it will need to be enough to protect governments from paying exorbitant amounts, but not so much that it raises the costs of operating in space and dampens growth in the space industry.

This article has been previously published on Rotoiti, an Auckland-based consultancy supporting the space industry with market research, strategic advisory, and business development services. Read and download the original article here.

Nicholas Borroz is the founder of Rotoiti, an Auckland-based consultancy supporting the space industry with market research, strategic advisory, and business development services. He previously worked in business intelligence in Washington, DC, where he coordinated a global subcontractor network to support clients in numerous industries with risk management, due diligence, and compliance. Nicholas received his PhD in international business from the University of Auckland, his MA in international economics from Johns Hopkins SAIS, and his BA in international relations from Macalester College.