by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 6 – 12 September 2021”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 6 – 12 September 2021”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup! A special shout-out to our friends at GoTaikonauts!, and at SpaceWatch.Global, both excellent sources of space industry news. In particular, we suggest checking out GoTaikonauts! long-form China reporting, as well as the Space Cafe series from SpaceWatch.Global. Without further ado, the news update from the week of 6 – 12 September 2021.

1) After the rumors on the iPhone 13 satcom capabilities, the Chinese discuss similar capabilities with Chinese smartphones

Jean’s Take

Renowned Apple analyst Ming-Chi Kuo took the world by storm last week when he predicted that iPhone 13 would support some satellite connectivity features using the Globalstar LEO constellation. The extent of the satellite connectivity features is still blurry, but Bloomberg hinted that it would probably be limited to sending short text messages to first respondents, in the context of an emergency occurring in a remote area with any traditional 3G/4G/5G connectivity.

Why are we mentioning this on the Dongfang Hour? Because this news also had an impact in Chinese circles, and became one of the hot topics of the week. One must understand that China prides itself on being a smartphone manufacturing powerhouse, with 3 of the 5 top global manufacturers being Chinese (Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo) and with Xiaomi overtaking Apple as the world’s 2nd largest smartphone manufacturer in Q2 2021 (in volume). So Apple releasing a new pioneering technology in their upcoming iPhones was potentially a hit on the ego.

Some Chinese netizens notably pointed out that there were already Chinese smartphones that supported such features, and that this was notably made possible thanks to China’s Tiantong S-band GEO communications constellation, of which 3 satellites (Tiantong 1-01, 02 and 03) are already in orbit since 2016. An example of such a smartphone terminal is the Linyun YT-8000 smartphone, which is a 5G smartphone that supports 5G frequencies as well as Tiantong communications.

Other netizens nevertheless noted that such phones as the YT-8000 were a different market (just look at the Linyun’s more “rugged” look, and its thickness at 2.5x that of the iphone). The price point at nearly 2500 USD probably make it a niche product for people working in remote areas.

And there are also additional limitations compared to the theoretical iPhone 13 satellite features: Tiantong satellites do not have a global coverage just yet, they only cover Asia Pacific (although there is talk of a global coverage with future Tiantong 1-04 and -05 satellites), and the frequencies used are not compatible with European and North American markets, which already use the same frequencies as Tiantong for other applications.

Finally, Tiantong is a GEO constellation, at 36000 km of altitude, compared to GlobalStar or Iridium which are LEO constellations. This means that any antenna supporting Tiantong will have to have a significantly higher gain → higher costs, and probably bulkier phones.

A possibly more credible candidate for “China’s 5G + satellite smartphone” could be the upcoming Huawei Mate 50, which was reported by the Chinese media to potentially support similar emergency messaging features as the iPhone 13. But this time, the technical enabler for satellite short messages is the Beidou-3 constellation.

The constellation is composed of 24 MEO, 3 GEO and 3 IGSO satellites. It provides the classical satellite navigation and positioning services similar to GPS, as well as more precise positioning services (RTK, PPP, SBAS, …). But one unique feature of Beidou-3 compared to other satnav constellations is that it enables a global coverage of a short messaging system, limited to 1000 Chinese characters in China & the Asia Pacific area, and 40 Chinese characters beyond that.

Beidou-3 chips enabling such two-way messaging applications were reported to now be below 3W of power consumption, making their integration in smartphones possible. In a recent report on September 2, CCTV mentioned that such smartphones would hit the market before the end of 2021.

Blaine’s Take

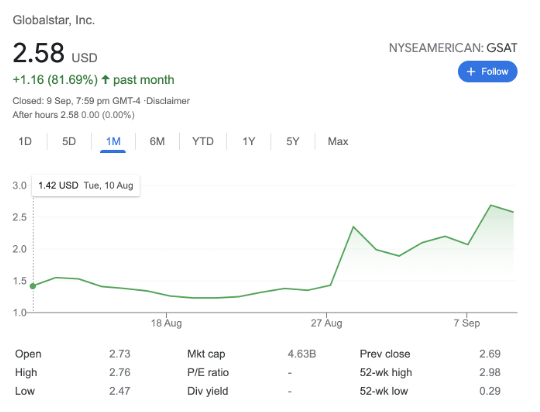

Just a few points from my side: first of all, apparently excellent news for Globalstar–their stock is up 80% in the past month.

Just a few points from my side: first of all, apparently excellent news for Globalstar–their stock is up 80% in the past month.

Regarding the comparison between Globalstar/Iridium and Tiantong, another issue with Tiantong being in GEO is that latency is considerably longer than for LEO–up to 400ms for GEO, or 4/10 of a second. Not devastating, but definitely too long to be playing online games, and long enough to be annoying during a phone call.

Separately, the idea of integrating existing smartphones with satellites has been around for a little while. As early as 2013, mobile satellite operator Thuraya released its SatSleeve product, a sort of encasing that can be put onto existing smartphones and enable them to connect to Thuraya MSS satellites, also in GEO. Similar to Tiantong phones, the SatSleeve is designed to be low bandwidth, but it is interesting in that it can integrate with a standard iPhone or Android.

I would mention that the update from Apple is not the only alleged satellite-to-smartphone integration plan. Among others, a company called AST Space Mobile has plans for integrating its planned LEO constellation directly with cell phones, aiming to provide global broadband connectivity. AST has partnered with Japanese mobile network operator Rakuten, and claims to have many patents related to the technology. The plan is considered technologically very tricky if not downright questionable, but investors have seemingly shrugged it off, with ASTS trading at a market cap of more than US$2B. As a point of comparison, satellite operator Eutelsat, with revenues of ~US$1.5B per year, and with a global fleet of satellites, is worth around US$2.5B. That is, a largely paper company that plans to build a technology we have never seen before is worth nearly as much as the world’s third-largest satellite operator. Efficient market hypothesis may have gone out the window, but apparently investors are very keen on direct communication between satellites and smart phones. In addition to ASTS, we have also seen rumors of Starlink planning a direct-to-cell service, though this is not confirmed.

Moving forward, we are likely to see several trends continue. First, the internet is going to continue to become more mobile-oriented as smartphone ownership and use increases. Second, LEO broadband constellations are likely to continue deploying, at least for a few more years. The long-term prospects for LEO broadband, and also for satellite-to-phone broadband communications, are both uncertain, but for the short-medium term, it appears to be an important enough opportunity to where investors are going to continue pouring money into these ventures.

Final point: I highly recommend the book Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story. I am currently reading it, and there are a ton of excellent insights and anecdotes about the heady days of the early LEO broadband constellations in the 1990s and 2000s. Great lessons to be learned for the new generation of constellations.

2) Article on China’s Provincial Space Policies

Blaine’s Take

Monday this week saw an very comprehensive article published by Satellite World (卫星界) about China’s national and provincial space policies. The first main takeaway from this article is the sheer number of space policies mentioned, and the extent to which basically all of them were made in the past several years, with most having been passed since early 2020. Overall, a full 15 provinces and provincial-level cities have passed specific space-related policies in the past ~18 months. A few policies stick out in particular:

At a national level, we have several policies passed by the State Council, China’s highest political body, including February 2021’s “National Comprehensive Plan for a Multi-layered Communication Network”, as well as the “Opinions on Advancing the Quality of Weather Modification Program”, with the former supporting the development of multiple satellite constellations, and the latter calling for use of meteorology satellite data for weather modification (for a great article about China’s weather modification efforts more generally, check out this one in The Economist from May 2021, though it may be paywalled).

At a provincial and city level, there are a truly astonishing number of initiatives being geared towards the satellite and space sector. As noted, there are 15 provinces with space-related initiatives in the article, and within these 15 provinces, there are a total of 24 different policies related to space. We have discussed several of these policies on the Dongfang Hour before, notably last month when we discussed Guangdong having added satellite internet to its 14th Five-Year Plan.

Several of the policies are admittedly only tangentially related to space, or otherwise are much broader policies that have some relatively small space component. For example, in March 2021, Ningxia apparently passed a “2021-2023 Plan to Build Digital Governance”, which included, among other things, accelerating the development of GIS systems, integrating BeiDou with Gaofen EO satellites, and increasing data collection.

Overall, definitely a major emphasis on BeiDou, EO, data collection, and digitization of everything. As we have discussed at length on the DFHour, the Chinese development model has its benefits and drawbacks, and all these regional development plans highlight both. On the one hand, there are a lot of resources being poured into highly strategic industries, by entities that have the ability to “move the needle” in terms of development. On the other hand, several of the initiatives look pretty similar to one another, and the sheer number of initiatives indicates some level of potential inefficiency, or at a minimum overlap.

Moving forward, we can probably be sure of two things. 1) China’s space sector is going to continue developing at both a national and provincial/city level, propelled in part by government initiatives, and 2) there may be some underutilized space assets in the medium-long term as many, many provinces and cities subsidize space sector development.

3) Plethora of Launch Updates

In the same week, we also saw two launches from China’s state-led satellite program.

Jean’s Take

- ChinaSat-9B

The first and largest one was ChinaSat-9B, a massive GEO telecommunications satellite based on China’s domestically-designed DFH-4 platform, and launched on-board a Long March 3B on September 9.

The DFH4 satellite platform is still today the main platform used for GEO communications satellites, and I say this because the previous generation platform, the DFH-3, was reported to be produced and launched for the very last time on July 6th 2021 with the launch of the Tianlian 1-05; and regarding the newer, heavier and more powerful DFH-5 platform, which was launched (successfully) for the first time in December 2019, we haven’t seen or heard much about it recently.

Back to the ChinaSat 9B, the satellite will focus on direct broadcast, providing 4K/8K high-definition video to users on the ground notably during large scale events such as the upcoming Beijing Winter Olympics of 2022.

Last point (more of a fun fact), there were some absolutely stunning shots of the rocket flames shooting out of the engines of the LM-3B, taken by a Weibo account called “爱科学的好少年”. There’s a lot of information to be understood by looking at these photos: you can see the blue-ish transparent flame coming from the exhaust of the engines burning UDMH/N2O4. But you also see some brighter flames coming from the exhaust of the preburner (the brighter color of the flames here is coming from the fuel-rich nature of the combustion), and you also see orange puffs of smoke coming from unburnt N2O4, which decomposes into the orange-brown NO2 at ambient temperature.

And that will be all for the rocket nerd sequence, handing it over to Blaine for the 2nd launch of the week.

Blaine’s take

- Long March-4C Launches Gaofen-5-02

On Tuesday we saw a Long March-4C launch the Gaofen-5-02 EO satellite from Taiyuan, with both the satellite and rocket manufactured by SAST. A few points worth noting: this was CASC’s 30th launch of 2021, and they have succeeded in all 30 of them. The company plans for 40 launches in total during the year. This was also the first time that a LM-4C was equipped with data relay capabilities on its third stage, which allowed for continuous telemetry data transfer between the rocket and the ground relay stations, using the Tianlian relay satellites. As noted earlier, this would have been continuous, but with a bit of lag, with the signal needing to travel ~36,000km to GEO orbit, then 36,000km back to the ground.

Back to the satellite: the Gaofen-5-02 is apparently equipped with 7 remote sensing instruments, and was sent to a 705km sun-synchronous orbit. Based on the SAST3000 bus, the Gaofen-5-02 represents one of the larger and more sophisticated satellites built by SAST. The satellite is equipped with hyperspectral equipment and is intended to monitor atmospheric conditions, water conditions, and the environment more generally.

Final point from my side: impressive turnkey mission conducted by SAST. We have seen quite a few such missions this year, where the Shanghai-based CASC subsidiary is the prime contractor for both the rocket and satellite, and with both being pretty big and complex. In the case of GF-5-02, the satellite weighed several tons, and the LM-4C is a beast of a rocket. Well done to SAST, impressive mission!

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space