by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 5 July – 11 July”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 5 July – 11 July”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup! A special shout-out to our friends at GoTaikonauts!, and at SpaceWatch.Global, both excellent sources of space industry news. In particular, we suggest checking out GoTaikonauts! long-form China reporting, as well as the Space Cafe series from SpaceWatch.Global. Without further ado, the news update from the week of 5 July – 11 July 2021.

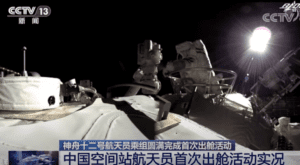

1) China’s 1st EVA with Tianhe (and 2nd ever EVA)

Jean’s Take

Taikonauts Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo successfully completed a 7-hour EVA on July 4th, marking the second EVA ever by China, the first one being in 2008 with the crew of Shenzhou 7. (EVA is extra vehicular activity, basically having astronauts get in pressurized space suits and conducting activities in the vacuum of space).

The EVA is one of the highlights of the Shenzhou 12 mission, after barely 2 weeks in space (Shenzhou 12 docked with the Tianhe module on June 17).

To briefly go over how the EVA took place:

- The 2 taikonauts which are to actually perform the EVA first moved to the multi-docking node section of the Tianhe module. The remaining taikonaut, Nie Haisheng, who’s the commander of the mission, remains in the cylindrical parts of the Tianhe core module.

- Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo then dress up in their EVA suits. All hatches are closed, notably the one to the rest of the Tianhe module and the one to the Shenzhou spacecraft orbital module.

- The node is then depressurized to equalize pressures with the vacuum of space (of course the air is not wasted, it is pumped back into the space station).

- The taikonauts then open the EVA hatch (at the top of the node) and are able to go outside. A protective cover was placed on the exit hatch.

The first task of the taikonauts involved work on the robotic arm. Nie Haisheng controlled the robotic arm from inside the Tianhe core module, while Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo worked together to put a number of additional systems (foot restraints, work station) that would enable the robotic arm to move the taikonauts around.

Next, Tang Hongbo moved to an area between the small and large cylindrical modules of Tianhe, shortly followed by Liu Boming. This is the area where you have the panoramic camera, and Tang Hongbo added an extension (nicknamed the “selfie stick”), so it would elevate the camera and have a better field of view. As the article from China Aerospace News suggests, these are operations that have been rehearsed countless times by the taikonauts during the underwater training sessions.

The final task was an emergency return drill, during which Tang Hongbo had to move to the area on the tianhe module that was furthest away from the node, and then return as quickly as possible. The idea is to train taikonauts to evacuate in case of life support system issues or if the space station encounters an area of space with a strong concentration of debris.

Once this was completed, the taikonauts returned to the node, Liu Boming disassembled the foot restraints and work station on the robotic arm, and the taikonauts returned inside the node, closed the hatch, and engaged the recompression of the node module.

Only once this was complete could they take off their EVA suits, open the hatch, and return into the Tianhe core module living quarters.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/r-6LPDLL9KdId9-flfhT-Q (image of tools, discussion on WiFi in and outside of the cabin)

2) Plethora of launches in a single week

Blaine’s Take

In just one week, we saw China perform a total of 4 launches, a rare occurrence even for a country which plans 40+ launches in 2021. This is made possible also because China has multiple launchpads and preparation of each launch can be done in parallel.

The first launch occurred on July 3rd at Taiyuan launch center with the launch of a Long March 2D. The main payload was the Jilin-1 Kuanfu-01B, a high res sub-meter level resolution satellite built by EO company Charming Globe, and believed to weigh 1.25 tons. The 4 other payloads were 3 Gaofen-3D satellites, which are EO satellites also for Charming Globe’s EO constellation Jilin-1. The fifth and final payload was Xingshidai-10, which will be part of Chinese company Adaspace’s “AI” remote sensing constellation Xingshidai. The launch was covered in a bit more detail in last week’s episode of the Dongfang Hour, as it took place on Saturday the 3rd. Overall, a good example of the diversity of stakeholders that we have seen in various Chinese launches. In this case, we have CGSTL as the “anchor”, Inner Mongolia (in partnership with CGSTL), ADASpace, and quite possibly due to their regular involvement with ADASpace, the government of Chengdu.

The second launch took place at the Jiuquan launch center on July 5th (China time), putting the Fengyun-3E into orbit on-board a Long March 4C. The Fengyun-3E is part of the second generation meteorological satellites of China (which are the Fengyun-3 and Fengyun-4). The Fengyun-3 are in SSO, while the Fengyun 4 are in GEO. For more info on the Fengyun-4 satellites, be sure to check out our DFHour from a few weeks ago which covered the launch of the Fengyun-4B to GEO.

While meteorological satellites are generally placed in an orbit in order to have a morning or an afternoon flyover, the Fengyun-3E is a “twilight” satellite, enabling shots at 5:30 am and 5:30 pm.

Another more general takeaway from these two launches is the number of EO (and in some cases meteorological) satellites being launched by China. This is a major trend over the past several years, and more recently, we have seen sub-segments of the EO market become quite “hot”, with this including Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) EO satellites, of which we have seen several launched by China in the past few months. There are likely several reasons for this. First, one might argue that there is objectively a lot of demand for EO data and related services in China, from sources like local/provincial governments and companies. Second, however, is the fact that in the context of satellites, EO is seen as the “least regulated” in China, being far more open than communications or satellite navigation (both of which are the purview of the state). Last point on EO before Jean brings us to the 4th launch of the week–we did see earlier this week a report published by Jiage Tiandi (an EO downstream data analytics company) and 36kr (a startup news website) about the EO industry in China.

Jean’s Take

The third launch occurred the next day on July 6th A Long March 3C put a Tianlian 1-05 satellite into geostationary orbit. Interestingly, the launch comes at a time where the Tianlian satellites are being used intensively by China’s crewed space program.

Indeed, the Tianlian satellites are China’s geostationary relay satellites, which as their name suggests, are “relays” between Chinese spacecraft in LEO and ground stations. Rather than having direct communications between a spacecraft in LEO and ground stations, signals are sent to the relay satellite which then transmits the signal to the destination spacecraft or ground station. This notably solves the problem of otherwise having to deploy ground stations over the whole planet.

Tianlian satellites are notably what enable the Chinese space station to maintain near-continuous communications with Chinese ground control. With 3 GEO satellites placed strategically, you are able to provide worldwide coverage.

China started deploying its Tianlian-1 series of satellites in 2008, achieving worldwide coverage in 2012 (with the launch of Tianlian 1-01, 1-02, 1-03). While providing global coverage, the Tianlian-1 satellites have a life expectancy of 8 years, and so China began sending replacement satellites in 2016 with Tianlian 1-04, and now Tianlian 1-05 in 2021.

The Tianlian 1-05 is the last of the Tianlian-1 satellites to be sent into space, as China started to deploy the 2nd generation of relay satellites, the Tianlian-2, in 2019, with the Tianlian-2-01. The Tianlian 2 series are based on the more modern and heavier DFH-4 platform, enabling higher data transfer rates than the Tianlian 1 series.

On July 9th, a Long March 6 sent a cluster of 5 Ningxia-1 satellites. This is the second cluster of satellites from the Ningxia constellation being launched, the first 5 having been launched in 2019, also on an LM6.

The Ningxia constellation, which also goes by the name of the Zhongzi (钟子号卫星星座), is a mysterious one. From what we can get from Chinese discussions, it seems to be SIGINT constellation managed by a company called “Ningxia Golden Silicon Information Technology” (宁夏金硅信息技术有限公司). It claims to be a “commercial” SIGINT company, although customers for SIGINT would probably mainly be military customers, so the “commercial” sticker is all relative. The manufacturer of the satellites are a CASC subsidiary Aerospace Dongfanghong.

So in conclusion, definitely one of the more mysterious Chinese constellations, based in the smallest province of China: Ningxia.

Last point worth noting, it was reported that the Long March 6 which was used for the launch, used a new improved 3rd stage.

3) Guangzhou and Tianjin Add Satellite Internet to their Development Plans

Blaine’s Take

The cities of Guangzhou and Tianjin added satellite internet to their development plans. In the case of Guangzhou, satellite internet is being used as one tool for the construction of a digital pilot zone, while in the case of Tianjin, the city’s 14th Five-Year Plan involves a satellite component.

In Guangzhou, we have an “Implementation Plan for Building a National Digital Economy Innovation and Development Pilot Zone in Guangzhou”, with one of the tools being used to build it being satellite internet (in addition to some far-out ideas like quantum communication networks and 6G). In general, the plan calls for increasing digitization of everything in Guangzhou, with specific calls for a “high-speed intelligent network of all things”, as well as for building 38,900 5G base stations in Guangzhou by 2022. Other elements of the plan include strengthening digital public services, creating an artificial intelligence and digital economy experimental zone, and by 2022, have the city’s software and information services industry reach an output of ¥600B. One final point on Guangzhou–interesting that earlier this week, we also saw EO data analytics company PIEsat set up a South China HQ in the city of Foshan, which is in some respects a very large suburb of Guangzhou.

In Tianjin, we saw the city publish its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), which included several significant space elements. Notably, the city aims to reach batch production of the Long March-5, 7, and 8 rockets while making progress in developing rocket components. The plan also calls for building a satellite internet production line with an annual output of more than 100 satellites, while also making reference to the national satellite broadband plan. Finally, Tianjin hopes to carry out final assembly and testing of super-large spacecraft such as core and test modules of the Chinese Space Station, reaching an annual capacity of 6-8 spacecraft including testing capabilities.

Quite a bit to unpack here, particularly with Tianjin. The port city near Beijing is already home to the manufacturing facilities of several of China’s largest rockets, so the batch production of the LM-5, 7, and 8, while an interesting detail, is itself not so surprising. Building a satellite production line with a capacity of 100 satellites per year is more interesting, as it gives us clues to CASC/CAST’s activities in Tianjin. Over the past several years, CASC has mentioned a satellite factory being built in Tianjin with a production capacity of 130 satellites per year, but with very few updates on its status (especially when compared to CASIC’s activities in Wuhan and their very regular updates on the satellite factory there). While not specifically mentioning the CASC production line, the mention of a >100 satellite per year capacity production line in the city’s 14th FYP is a pretty not subtle hint.

Overall, yet the latest example of cities getting in line with the NDRC’s addition of satellite internet to their New Infrastructures list. Moving forward, so many cities doing so many things with a relatively limited degree of coordination will likely lead to inefficiency, but it may well also lead to a sprawling and powerful space industrial base.

Jean’s Take

It’s interesting to see the very many initiatives from local municipalities and provinces to develop the local space industry, and these initiatives have really been gaining momentum in recent years. This is why you see more and more Chinese commercial space companies moving or relocating to these cities (in the case of Guangzhou, you have the Nansha Aerospace base with CAS Space and GeeSpace; Tianjin you have Tianbing Aerospace), when most of these companies would have probably set their headquarters in Beijing a mere 5 years ago.

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space