Editor’s Note: SpaceWatch.Global is proud to welcome Blaine Curcio and Tianyi Lan as guest columnists on China’s commercial and New Space scene. Today we publish their first monthly column.

By Blaine Curcio and Tianyi Lan

The China Commercial Aerospace Forum (CCAF) 2018, held in Wuhan in late September, was significant for a variety of reasons. Occurring in the latter part of the most dynamic year in Chinese commercial aerospace history, the conference was buzzing with activity and optimism, and saw representatives from both private and government space companies in attendance exchanging ideas and discussing trends.

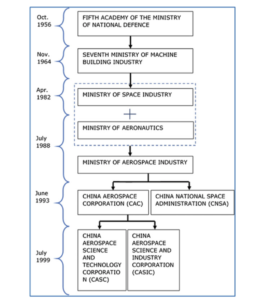

Up to fairly recently, the Chinese space industry and the Chinese space-related state owned enterprises (SOEs) were synonymous. The overwhelming majority of the Chinese space industry was accounted for by state-owned aerospace giants China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp. (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corp. (CASIC). These two companies have evolved out of the Chinese Ministry of Aerospace Industry, and remain under the umbrella of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Council (SASAC).

Throughout its history, CASIC has focused more on defense products, whereas CASC has been a more purely space company. CASIC’s mandate has thus been broader, with the company targeting “land, sea, air, space, network, and electromagnetism.” Conversely, CASC, and its many subsidiary companies such as China Great Wall Industry Corp. (CGWIC), China Academy of Launch Sciences (CALT), China Academy of Space Technology (CAST), etc., have established themselves as the dominant players in the Chinese space industry, while consequently being narrower in focus.

As of 2017, the two companies are essentially identical in terms of revenue, at slightly more than U.S.$34 billion each. This makes CASC and CASIC the 343rd and 346th-largest companies in the world by revenues, respectively. By comparison, Lockheed Martin’s 2018 revenues were around U.S.$51 billion, and Airbus’s were U.S.$75 billion. The strategic direction and composition of these two giants has been changing rapidly as of late, particularly as it relates to the space and aerospace industry. This has involved a move towards partial privatization, and increased competition in some areas.

A Partial Opening of a Closed Market

One of the key initial moments in the commercialization of the space industry in China came in March 2014, at that year’s annual People’s Political Consultative Congress in Beijing. During the event, Baidu (the Google of China) founder Robin Li, a multi-billionaire entrepreneur, was quoted as advocating policies that “encourage private players to enter the aerospace sector, including rocket and satellite launching…to enhance the international competitiveness of China’s aerospace industry.” This was arguably the first time a significant private sector figure strongly and publicly endorsed the development of a private space industry in China.

The government acted on Robin Li’s advice remarkably quickly, with Prime Minister Li Keqiang (China’s second highest-ranking official) announcing at the October 2014 State Council meeting that the government would promote investment into five “key fields”, including specific areas that Li had highlighted eight months before, such as launcher development, remote sensing satellites, etc. One month later, the government announced via its State Council’s website that the government had made the decision to open the space industry further, in particular for a “civilian space infrastructure.”

CASC, CASIC, and Efforts to Privatize and Commercialize

The two biggest companies to heed this call have been CASC and CASIC, and both have started to make a push towards commercialization of their subordinate companies. CASIC has commercialized more quickly since the deregulation in 2014, coming into more direct competition with CASC in some areas, a stark change from pre-2014.

CASIC’s main space industry activities prior to 2014 included spacecraft or launch vehicle subsystems, design, or components, with CASC being the main contractor to the government and CASIC playing a secondary role. Following partial industry deregulation in 2014, CASIC Chairman Mr. Gao Hongwei pushed a plan for increased involvement of private space companies. For this reason, CASIC’s annual sponsored event is the CCAF. Part of the motivation behind the CCAF is to create a platform for CASIC to announce its major projects, with the private companies in attendance being able to adapt their business models in support of these mega-projects.

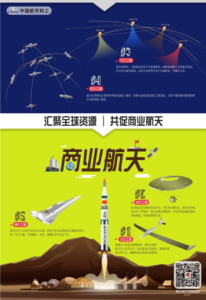

CASIC’s major announcements over the past four years at CCAF have included the 16+4+4+X remote sensing constellation plan unveiled in 2015, which has since become SpaceView, a company with four high-resolution optical satellites in-orbit and plans for four more. Also of note was the announcement of CASIC’s “Five Clouds” plan in 2017, with this including proposals for both a broadband and narrowband LEO constellation, in addition to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and high-altitude pseudo satellites (HAPS). The company has stated that the cost of the “Five Clouds” projects may exceed RMB 100 billion (~U.S.$14 billion). For a company with the above-mentioned annual revenues of U.S.$34 billion, this seems plausible, financially.

In conjunction with the Five Clouds plan, CASIC has announced the creation of the National Aerospace Industrial Base, also in Wuhan. This involves a series of companies and projects aimed at achieving an output of 50 launch vehicles, 40 commercial satellites above 100kg, and 100 commercial satellites below 100kg by 2020, with an annual output of 30 billion yuan (~U.S.$4.5 billion). Headquartered in this base are well-funded CASIC startup companies, including launch company Expace (funding: U.S.$180 million), and constellation company Xingyun, part of the above-mentioned Five Clouds. A noteworthy point to consider is that Expace is the first nominally private (though CASIC-funded) Chinese launch company to make commercial launches into orbit, on its Kuaizhou-1A rocket. The company successfully completed its second commercial launch in September 2018.

The Scene at This Year’s CCAF

Many of CASIC’s plans were on display at this year’s CCAF in Wuhan. The above-mentioned commercial launch of Expace’s Kuaizhou-1A occurred just two days after the end of the Forum, and a model of the launch vehicle on its mobile launch platform featured prominently at the CASIC booth, itself at the very front of the exhibition hall. The company made concrete announcements for the total planned capacity of its Hongyun LEO broadband constellation, at 600 Gbps from 156 satellites. These are noteworthy projects in that they are under the CASIC (i.e. state-owned) umbrella, but are privately run, and in some instances are competing more directly with CASC.

The increasing commercial efforts of CASIC, and to some extent CASC, may expand the opportunities for the commercial space industry in terms of R&D and production, by pushing more space activity into lower-cost areas. For example, the CCAF took place in Wuhan, a city in central China. Compared to Beijing—the traditional space industry center, the cost of living, talent, and land in Wuhan is cheaper by half or more. CASIC’s Wuhan Aerospace Industrial Base may open the door for more companies to enter the market, and the generally lower cost of everything may encourage somewhat higher risk tolerance by startups.

Overall, the increasing commercialization of CASC and CASIC will be a double-edged sword for the more purely commercial Chinese space companies. A more commercial-focused CASIC/CASC is a strong competitor to private players in the fast-changing small-medium launch markets, among other industries, and CASC/CASIC will almost certainly benefit from more favorable regulatory treatment due to their SOE status. However, CASIC and CASC’s successes also bring more positive attention to the space industry, on both a governmental and societal level, and up to this point, it has been a rising tide lifting all boats due to significant new funding coming into the industry more broadly. On the whole, despite the proliferation of private money and new startups in China’s space industry, the most apparent takeaway from the CCAF was that CASIC (and also CASC) remain the biggest players in the industry by far, and that they will not yield market share to upstarts without a fight.

Blaine Curcio is the founder and owner of Orbital Gateway Consulting, a boutique market research and consulting firm focusing on emerging commercial opportunities in space and satellite industry, as well as the Chinese space/satcom market. Blaine is also a senior affiliate consultant for Euroconsult, and is based in Hong Kong. Blaine can be contacted at: [email protected]

Tianyi Lan is the founder and CEO of Ultimate Blue Nebula Co. Ltd., a space and satellite consulting company. Tianyi is also the CEO of SpaceKey and was formerly an engineer at the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST). Tianyi Lan is based in Beijing. Tianyi can be contacted at: [email protected]