by Ralph Thiele

This is the second part of an op-end article reflecting the EuroDefense network ongoing work from several national chapters with the objective to recommend a common ambitious high-level vision for European advancement in the Space Domain as it proves critical to Europe’s prosperity, security and defence. Europe should build a space strategic culture that accentuates its strengths, minimizes its weaknesses and articulates and justifies its goals to the world and to itself.

Priorities and Recommendations for Europe

With the European documents of reference which have published the key priorities for Europe in terms of space in mind:

- Europe must ensure accessible, affordable and sustainable access to space services for European citizens and businesses as a precondition of continuity, resilience, growth and innovation;

- Europe must maintain itself as a leader in innovation and production in the aerospace field and must reduce the existing gap with regards to new technologies, such as reusability;

- Europe must build, maintain and protect space capabilities so that it will not be reliant on those of other powers. The next project in this regard is the secure government communications satellite system, GOVSATCOM;

- Europe must achieve resilience – i.e. the capability to resist space related stress and shock – to risks, vulnerabilities and threats deriving from its increasing reliance on space systems, both at the level of its militaries, and at the level of society and economy;

- Europe must create the toolbox with which to pursue its interests in a free and peaceful access to space, through a combination of multilateral agreements on rules of conduct, sectoral diplomacy and the development of instruments of deterrence against attacks on its space systems;

- European military capabilities must have safe and secure access to space services in order to maintain their edge in an environment beset by cyber and electronic warfare threats;

- Overall, Europe must integrate space into its toolbox for internal and external governance in all fields, from environmental and economic, to the security one;

- An improved level of public outreach in order to explain to EU citizens the benefits that space holds is paramount in raising awareness and support for the EU’s space component.

Recommendations:

- Europe should define and build a space strategic culture that accentuates its strengths, minimizes its weaknesses and articulates and justifies its goals to the world and to itself;

- While not militarizing per se, Europe should consider securitizing its space projects, starting with considering their utility for security, their impact on security and their requirements for security, in addition to the already included economic, environmental and social dimensions;

- Additionally, advances should be made in the quantum computing and communications sector. Here China and the US are clearly in the lead. These technologies will revolutionise the secure communications component of governments – to include armed forces – and the private sector as well as in a few years;

- The European Union should set up a Space Security Board as part of the Council on Space and working in close connection with DG-DEFIS to enable information sharing on these capabilities, it should conduct a European Space Defence Review as a part of evolving European Defence initiatives and capabilities.

- Cooperation between the EU and NATO on space should also be considered a continued priority. NATO does not have its own space assets and is reliant on information and asset sharing between member states for defence purposes. The EU’s significant space asset base can be included in a way which is more difficult for the individual NATO and EU Member States acting on their own initiative;

- Europe should focus on mobilizing its private sector resources and its entrepreneurialism to act as a multiplier to state-led investment into space. Europe has far fewer private investors into space start-ups than either the US, China and the UK.

- A potential approach towards stimulating the involvement of the private sector into space is to copy the EU approach for the InvestEU Programme 2021-2027, which has a security dimension related to cyber and AI, among others;

- The European Union should aim to employ the “Brussels Effect” to delay the militarization of space and the onset of space conflict, until it has closed the capability gap with its main systemic rivals. The Brussels Effect refers to the EU’s capability to set norms, rules and standards that are followed by entities outside the EU’s borders, and is a key component of European soft power;

- Provide support to Member States to organize Space Threat Response Architecture Exercises (the European variant of the French ASTER exercises) or various evaluations at national levels to increase awareness of critical dependence on space services and technologies;

- Begin developing dual-use technologies in space, including debris clean-up and mitigation technologies. One option to attain more of such dual-use technologies is to better synergise the civil, space and defence domains: how can each sector complement the other?

- The EU must focus on encouraging the development of private sources of funding, with appropriate appetite for risk, to complement state and EU investment in innovation and emerging technologies; the EU is far behind the US in this regard, when compared relative to size, population, GDP and overall economic sophistication;

- Strategic space autonomy cannot take place in the absence of strong private sector contribution, in financing as well as in the start-up scene; the EU must act at multiple levels, encouraging both European financing and European innovation, otherwise the financing gap will be covered by US entities, leading to brain and technology drains and affecting EU strategic technological autonomy, which has identified these threats from the imbalance in transatlantic potential;

- The use of prizes, both at the frontier of technical ability and for incremental capability development, should motivate the formation of teams that can then coalesce into start-ups;

- Stimulating the demand side for start-up products and services through a greater focus on and encouragement of new systems architectures and the services they provide.

A European Space Architecture

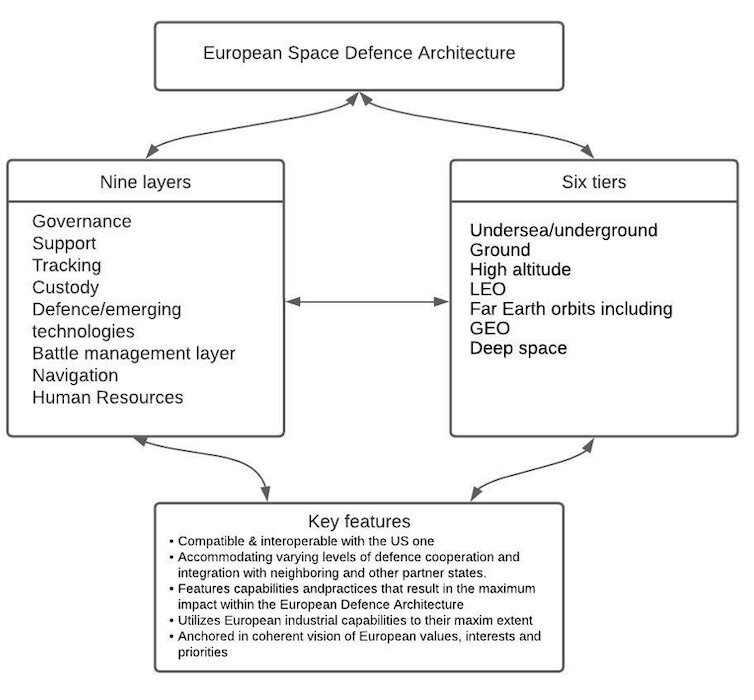

A future European Space Defence Architecture must be able to accommodate varying levels of defence cooperation and integration with neighbouring and other partner states. It must feature capabilities, but also practices that result in the maximum impact within the European Defence Architecture, such as the suggestion of including space resilience in operational planning from the previous section. Clearly, it should be compatible and interoperable with the US as we strive to cooperate in crises and conflict.

Consequently, mirroring the US model, we propose 7+2 layers of systems that feature redundant capabilities, interoperability between each other and with systems of allies and a logistics and industrial support system capable of rapid redeployment or replacement. These layers are as follows:

- The “support layer” is supposed to enable a common, resilient ground support infrastructure in order to facilitate the space-based capabilities of the other layers to transmit, receive, process, exploit and disseminate data.

- The “transport layer” is a space-based communication system for all the other layers that is supposed to provide assured, resilient, low-latency military data and connectivity worldwide to the full range of military platforms.

- The “tracking layer” will deal with advanced missile threats and will provide global indications, warning, tracking, and targeting of advanced missile threats, including hypersonic missile systems.

- The “custody layer” will accelerate the sensor-to-shooter interaction and sense and track objects on the ground down to the size of trucks and provide target-related information directly to weapon systems.

- The “deterrence/emerging technologies layer” is an enhanced space situational awareness (SSA) capability that also covers space from geostationary orbit to the region around the moon where traffic is increasing, but not well monitored yet. It is supposed to incubate new mission concepts to deter hostile action in the increasingly active region extending beyond the geosynchronous belt to lunar ranges.

- The “battle management layer” will provide autonomy, tipping and queuing, and data fusion for mission command & control to include time sensitive targeting.

- The “navigation layer” will provide alternate positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) for Global Positioning System (GPS)-denied environments. It is intended to come up – similar to the battle management layer – with onboard processing to provide navigation and launch data to the other satellites.

With view to the US space architecture, two additional layers – framing the other seven – are envisioned:

- The “governance layer” is made up of a framework of alliances and partnerships with differing levels of resource sharing and interoperability, as well as norms, standards and contacts that drive collective action and the harmonization of security perspectives;

- The “human resources” layer addresses a critical bottleneck for space, which is related to the availability of specially trained personnel in highly technical fields, which will require far more resources than available to militaries already stretched by the requirement for cyber-warriors. As even the civilian “human resources” will require security clearances, this will prove being a further considerable hurdle to achieve adequate quantities and qualities. Clearly, this will involve a close cooperation between private entities, academia and space-designated forces, as well as the capability to mobilize civilian capabilities and resources in case of necessity.

As part of the architecture, we also define six tiers of functioning – undersea/underground, ground, high altitude, LEO, far Earth orbits including GEO and deep space. Integrated space systems function across multiple planes with components located in each and with links primarily through communication but also through supplies and other types of dependencies. For instance, a simple space surveillance system for an unstable region could consist of a number of low-cost surveillance satellites strung out in orbit to provide permanent coverage; however, this is not the only component. It also features ground stations with privileged access to system functions and specific ground equipment, communication interlinks, redundant communication capabilities with the beneficiaries (for instance, through fiber optics to avoid ground jamming, or ground and space based quantum key distribution networks to protect highly classified information) and, in order to supplement capabilities on a short-term basis with new sensors, it could contain high altitude surveillance sub-systems such as surveillance drones or high-altitude balloons.

Conclusion

The space sector is undergoing a massive transformation. In view of its rapidly increasing importance, the European Union must embrace the new challenges ahead and seize the opportunities that present themselves. It has everything it needs to become a leading space power: gifted talent, outstanding research, technological leadership and remarkable industrial capabilities. Yet it lacks the conceptual underpinnings and, above all, the traction to tackle extraordinarily dynamic evolving challenges that involve not only the ambitions of national governments, but also a fast-growing and dynamic private sector that links both large and small industries, space and non-space ecosystems. To this end this paper recommend sa common ambitious high-level vision for European advancement in the Space Domain. Europe’s future prosperity, security and defence are at stake.

Ralph Thiele is President of the independent initiative EuroDefense Deutschland e.V., Chairman of the Political-Military Society and Managing Director of StratByrd Consulting. He is a strategy consultant, security expert, researcher, consultant and publicist. In his military career, he has held important national and international positions, including on the planning staff of the German Minister of Defence, in the cabinet of NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, as Chief of Staff at the NATO Defense College in Rome, as Commander of the Bundeswehr Transformation Centre and as Director of Teaching at the German Armed Forces Command and Staff College. Thiele advises in Europe, America and Asia on security topics in times of digital transformation. He is currently leading international research projects on hybrid threats and analyses current developments in new media, print media, radio and TV in the context of the war in Ukraine.