Historically, human space exploration was initiated by the Soviet Union with the Sputnik launch into the Earth orbit in 1957. Humankind’s space endeavors grew with more determination after the first animal’s launch, a dog called “Laika”. Marked by the Soviet Union’s Yuri Gagarin trip in the Vostok 1 in 1961 and his compatriot Valentina Tereshkiva’s three-day space orbiting mission in the Vostok 6 in 1963, humankind succeeded to make the giant leap beyond Earth’s boundaries.

Nonetheless, the Yuri Gagarin’s spacewalk and Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon remain the spark to ignite ambitious human prospects on space travel, which unleashed unlimited possibilities on the humankind’s expansion into outer space. The achieved milestones in space endeavors created a shift from a mere inspirational driver and curiosity feeder on existential questions [3] to a space race which grew from a bipolar race between the United States and the former Soviet Union to a different space race in which new actors, particularly private actors, have become essential players [4].

The most prominent ongoing transformation of the global space sector is the race to commercialize space driven by private enterprises and induced by governmental agencies who rewarded these enterprises billions of dollars in governmental space contracts. The evolution of space commercialization could be illustrated through the U.S. space economic emergence from the National Aeronautics and Space administration’s (NASA) monopoly to a more liberalized space sector. Such an emergence came as a consequence of NASA’s struggle to improve its military-based technologies to achieve cost-effective and safe space access [5] in addition to budget reductions and various costly accidents, which led NASA to outsource its spaceship manufacturing.

NASA’s outsourcing mechanisms were organized through public procurement contracts accorded through bidding mechanisms to a few private space giants. Under these procurement contracts, private entities undertook rockets and spaceships manufacturing supervised by NASA, who provided the launching facility. From 1982, private actors’ access to the space sector became less costly due to reduced entry barriers to the space sector [6].

Sparked by President Barak Obama’s policy in 2010, the space industry witnessed an unprecedented disruption characterized by decentralizing space activities from governmental entities to private sectors. As a consequence, the U.S. space sector has undergone a shift that impacted the global space sector. This shift was propelled by complex dynamics due to the interaction between various forces beyond simple market forces and driven by various factors. The combination of these factors, including the reduction of public entities’ involvement and the substantial private investment injection into the global space sector, created a diverse space sector [7]. The global space sector’s evolution created a revolutionary New Space market structure; thanks to its related complex geopolitics and complex forces, a new race started: the race to commercialize space.

In this New Space race, innovators and entrepreneurs burgeoned in the cradle of the New Space ecosystem, which included (1) space access firms specialized in payload launches into space (cargo and human), (2) remote sensing firms, (3) satellite data and analytics firms, (4) habitats and space station firms, (5) Low Earth Orbit (LEO) tourism, (6) beyond LEO firms, and research and investment firms [8].

The emerging new trends marked an unprecedented development, including the remarkable growth in launch service and ground equipment activities in the last five years [9] as well as the growth of more ambitious space endeavors [10], which was catalyzed by the private actors’ entry into the global space sector [11]. The diversified sector is characterized by different trends that vary from inter-sectoral interactions and dependencies and evolving national and international political and legal environments to a prominent socioeconomic impact that continues to justify public expenditures in the space sector [12].

Nonetheless, public investments continue to be one of the principal stimuli of the global space sector’s economic growth, driven by various funding programs aiming to achieve competitive advantages over other states‘ space capabilities amidst geopolitical tensions, support national security objectives, advance scientific and technological capabilities, and foster institutional governance [13].

The global space sector’s public funding has been increasing since 2008. Based on the Organization For Economic Co-operation And Development (OECD)‘s report “The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy,” the global space sector’s public funding has increased from USD 52 billion in 2008 to USD 75 billion in 2017. The latter was dedicated to Research and Development (R&D), public procurement, and various commercial space endeavors [14].

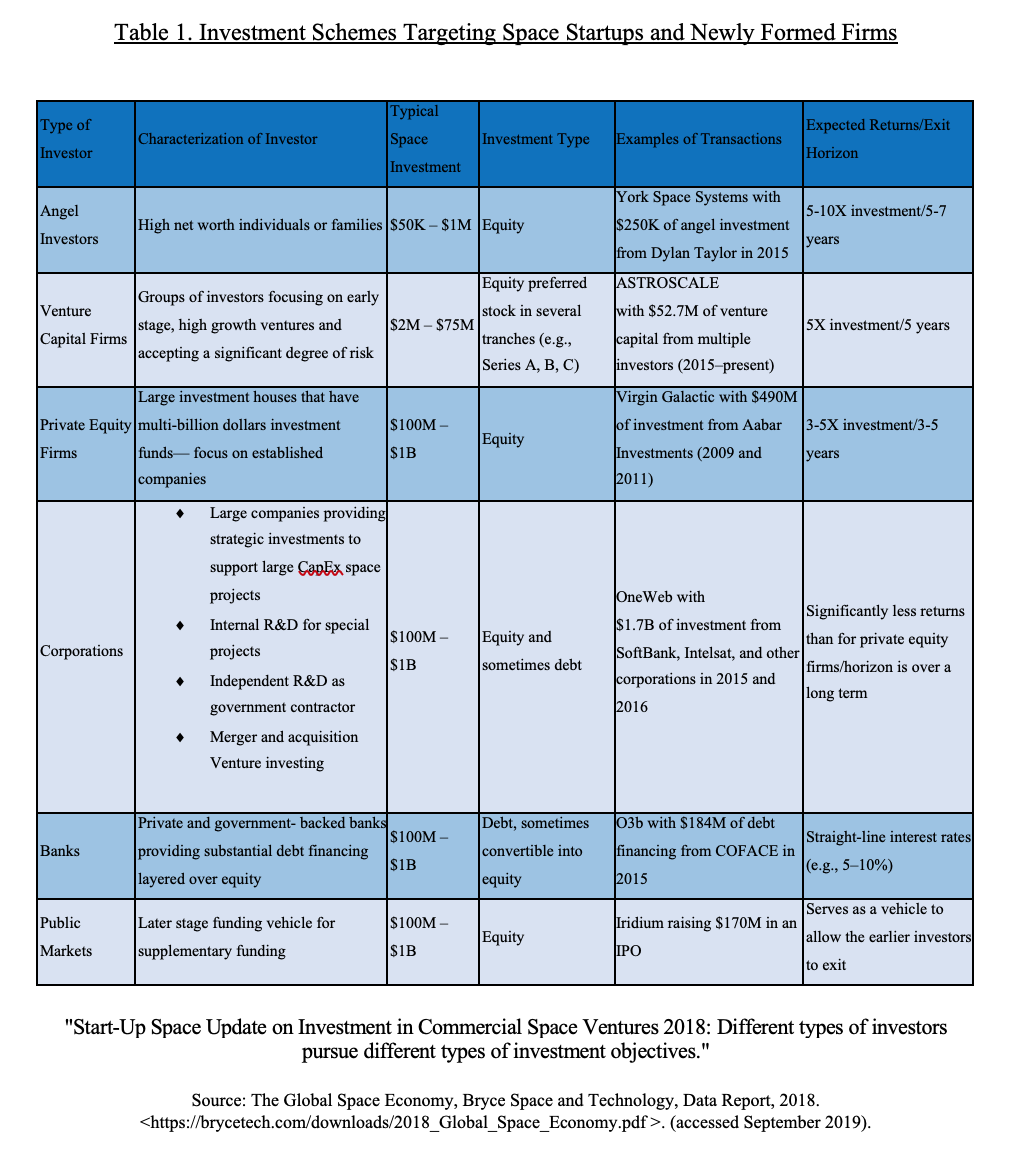

That being said, it is critical to state that the New Space sector has been witnessing new investment trends, which emerged to catalyze private space ventures [15]. The new investment trends that emerged to boost New Space activities have revolutionized the space landscape with Venture and Angel Capital Investments in space start-ups and billionaires’ investments in private space firms [16]. Table 1 in Annex 1 highlights the various investment schemes injected into major space start-ups and newly formed corporations since the New Space emergence.

Notwithstanding the challenges to track the different sources of global private space funding, Space Angels has reached its highest record for the twelve months in 2019 with an estimation of USD 5.8 billion,[17] while Seraphim Capital has reached USD 4.4 billion for the same period [18]. Globally, the investment injected into the private space sector grew substantially in the six years-period from 200 investment deals in 2011 to over 1,400 deals in 2017 [19]. Furthermore, based on Bryce Space and Technology Report, over USD 21 billion were injected in space start-ups from 2000 to the end of 2019. As per the same report, during 2019, start-ups attracted USD 5.7 billion, breaking the previous year’s record of USD 3.5 billion. During the same year, investors poured capital into the biggest space start-ups. SpaceX, Blue Origin jointly attracted USD 5.7 billion, while OneWeb attracted USD 1.25 billion, and Virgin Galactic raised over USD 682 million [20].

New Space investments were directed toward New Space activities, including space access, remote sensing, satellite data and analytics, space stations and habitat, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) tourism, beyond Low Earth Orbit activities, research and science, mining, and space investment venture [21]. Nonetheless, the access to space market may be considered one of the most significant markets in the space sector to witness an unprecedented disruption. New trends have emerged within the access to space market, intending to reduce the cost through reusability, economies of scale by maximizing the craft’s modularity, heavy launcher developments to carry a heavier payload for the leading players, micro-launcher developments for New Space entrants, as well as the use of LOX/ Methane propellant. However, access to space and satellite ventures carried by private actors are the main commercial space activities to attract private investors.

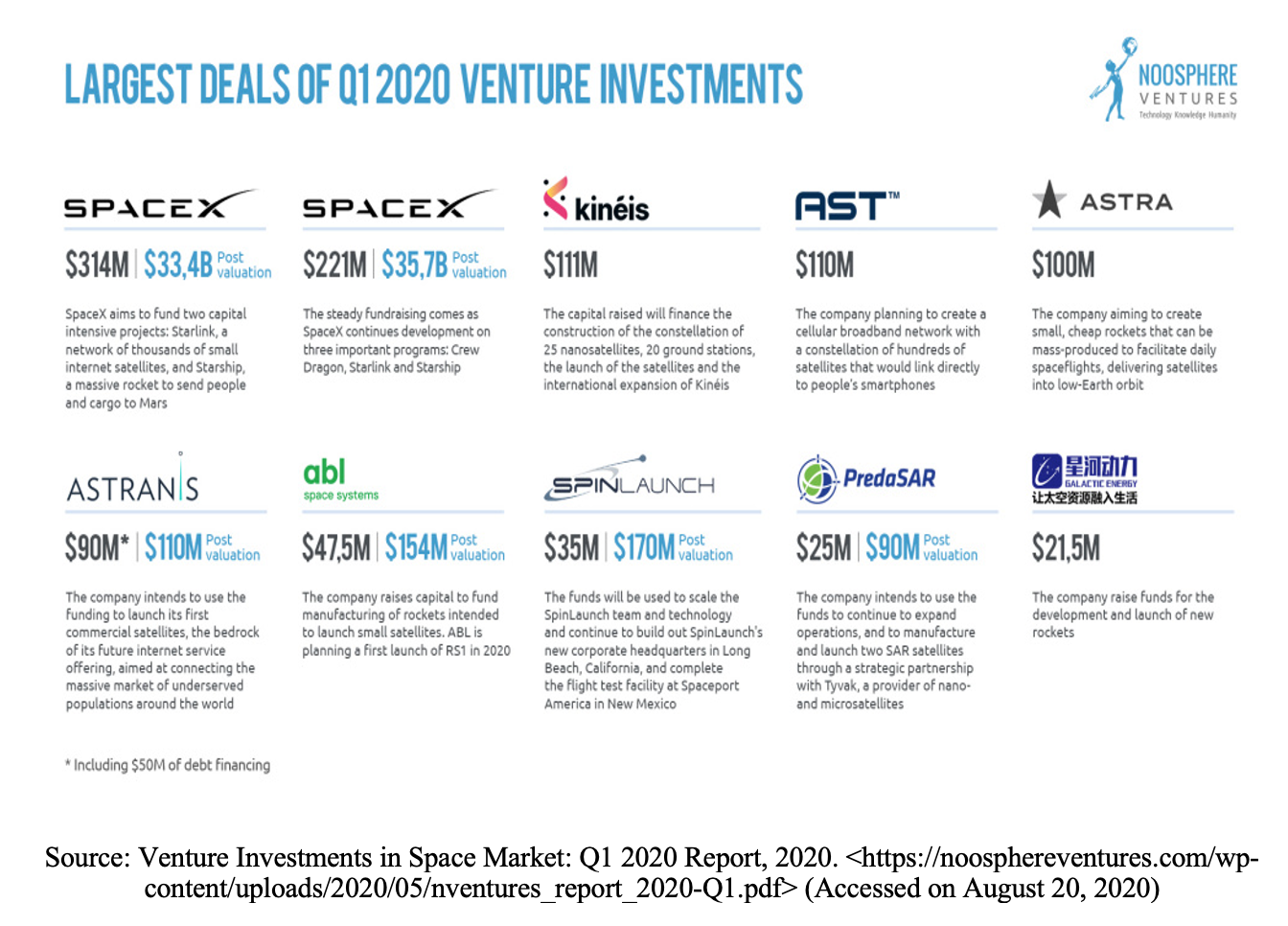

Taking private funding poured into access to space firms, the most substantial investments into such ventures in the first quarter of 2020 were made to SpaceX (ANNEX 2). The latter is the largest fundraiser with the two largest funding deals in the first quarter. The first announced funding deal was estimated at USD 314 million to fund SpaceX’s Starlink and Starship projects. Based on the same Report, the second SpaceX funding deal was estimated to be USD 221 million [22]. Recently, the unicorn which made most of the year’s media storylines completed a funding round to close the biggest fundraising operation of USD 1.9 billion [23].

SpaceX is now able to diversify its funding sources and reduce its reliance on governmental contracts, which were rewarded for inventing a space transport system to replace the retired NASA’s shuttle program. SpaceX’s unprecedented attraction to private investment came as a response to the firm’s successful cargo missions. Nonetheless, the most significant fundraising round was induced by the NASA’s astronauts’ successful mission, which will jumpstart routine crewed missions to the International Space Station (ISS). Additionally, the reliability of SpaceX, its technological disruption, and its vision attracted private investors. However, as the satellite industry remains the main lucrative space activity due to its market maturity, private actors continue to inject funds into this industry through classic financial schemes such as bank financing [24].

On balance, space has been witnessing an unprecedented paradigm shift due to the technological progress, increased funding, globalization, and digitalization. Investing in New Space has enabled New Space activities to flourish and has raised a plethora of new questions, in particular in the legal domain. How do we ensure that private space investments and assets are protected by international law and thus secure the flow of private money into space activities? The answer to this question will be addressed in a future article.

ANNEX I

ANNEX II

References

[1] Cousins, Norman, Philip Morrison, James Michener, Jacques Cousteau, Ray Bradbury, Why Man Explores, California Institute of Technology Symposium, Pasadena, July 2, 1976, California, NASA Educational Publication 123, Government Printing Office: Washington D. C., 1977.

[2] Patenaude, Monique, What Drives Humans To The Unknown?, Stewart Weaver Surveys Exploration Through the Ages, University of Rochester, 2015. <https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/journeys-into-the-unknown-91212/>. (Accessed on February 29, 2020).

[3] Nasa document

[4] Bockel, Jean Marie, The Future of The Space Industry, General Report of the Economic and Security Committee, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO Parliamentary Assembly, NATO Publishing, NATO, 2018, p 1.

[5] Slomon, Lewis D. The Privatization of Space Exploration: Business, Technology, Law and Policy, New York, 2017, Routledge, p 3.

[6] Jean Marie Bockel, The Future of The Space Industry, General Report of the Economic and Security Committee, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Nato Parliamentary Assemblee, NATO Publishing, NATO, 2018, pp 1-2.

[7] Deloitte, Sky is not the Limit, Building Queensland’s Space Economy, Deloitte Access Economics, 2019, ACN: 149 633 116.

[8] Mattew Weinzierl, Space The Final Economic Activities. Journal of Economic Perspectives, JSTOR (JSTOR)32(2018), 173-192, p 8.

[9] Jean Marie Bockel, The Future of The Space Industry, General Report of the Economic and Security Committee, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Nato Parliamentary Assemblee, NATO Publishing, NATO, 2018, p 5.

[10] OECD, The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy 2019, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2019, p 26.

[11] Jean Marie Bockel, The Future of The Space Industry, General Report of the Economic and Security Committee, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Nato Parliamentary Assemblee, NATO Publishing, NATO, 2018, p 1.

[12] PWC France, Main Trends and Challenges in The Space Sector, PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2019. <https://www.pwc.fr/fr/assets/files/pdf/2019/06/fr-pwc-main-trends-and-challenges-in-the-space-sector.pdf>. (accessed on August 18, 2020).

[13] Iacomino, Clelia, Commercial Space Exploration: Potential Contributions of Private Actors to Space Exploration Programs, European Space Policy Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology Series, Vienna, 2019, Springer, p 3.

[14] OECD, The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy 2019, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2019, p 18-19.

[15] Jean Marie Bockel, The Future of The Space Industry, General Report of the Economic and Security Committee, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Nato Parliamentary Assemblee, NATO Publishing, NATO, 2018, pp 1-2.

[16] OECD, The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy 2019, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2019, p 26.

[17] Space Angels, Space Investment Quarterly Q4 2019, Space Angels, January 14, 2019. <https://www.spaceangels.com/post/space-investment-quarterly-q4-2019>. (Accessed on March 1, 2020).

[18] Seraphim Capital, Seraphim Space Index October 2018 to September 2019, Seraphim Capital, October 22, 2019.

<https://seraphimcapital.co.uk/insight/news/seraphim-space-index-october-2018-september-2019-37-year-year-growth-44bn>. (Accessed on March 1, 2002).

[19] OECD, The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy 2019, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2019, p 26.

[20] Start-up Space, Update on Investment in Commercial Space Ventures, Bryce Space and Technology, Data Report, 2020. < https://brycetech.com/reports/report-documents/Bryce_Start_Up_Space_2020.pdf>. (Accessed on August 24, 2020)

[21] Mattew Weinzierl, Space The Final Economic Activities. Journal of Economic Perspectives, JSTOR (JSTOR)32(2018), 173-192.

[22] Venture Investments in Space Market: Q1 2020 Report, 2020. <https://noosphereventures.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/nventures_report_2020-Q1.pdf>.(Accessed on August 20, 2020).

[23] Vengattil, Munsif, Elon Musk’s SpaceX raises $1.9 billion in funding, Reuters, August 18, 2020

<https://www.reuters.com/article/us-spacex-funding/elon-musks-spacex-raises-19-billion-in-funding-idUSKCN25E26E>. (Accessed on August 24, 2020).

[24] OECD, The Space Economy in Figures: How space Contributes to the Global Economy 2019, Paris, OECD Publishing, OECD, 2019, p 26.

Malak Trabelsi Loeb: Senior legal associate specializing in International Business Law and International Space Law, Adjudicator, International Commercial Arbitrator. Entrepreneur, futurist, and strategist. Mrs. Loeb is a Lecturer in International Relations and Diplomacy, a multidisciplinary academic researcher, a writer and public speaker, and a Ph.D. Candidate in International Space Law. She is advocating for Sustainable Space For Humanity, addressing the complex Space socioeconomic and environmental interrelated dimensions. She is a human rights activist and strives to combat human trafficking and gender inequality. Mrs. Loeb has received the title of Champion of Tolerance from the UAE Ministry of Tolerance in 2018.