How should India approach Chinese efforts to develop antisatellite (ASAT) weapons and its ambition to establish space superiority? In a talk given to the Observer Research Foundation’s Space Security conference in New Delhi on 16 February, 2018, ThorGroup’s Dr. John B. Sheldon offers a few suggestions.

For those who have just emerged from living under a rock for the past five years or so, Geopolitics – with a capital ‘G’ – is back.

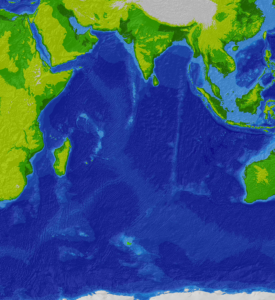

The return of multipolar Great Power competition across the Eurasian supercontinent, for dominance over the Indian and Western Pacific Oceans and their littorals, and access to the Northern waters of a receding Arctic, are also spurring competition among Great Powers and their commercial proxies in Earth’s orbits, and even beyond.

These geographical flash points and areas of contestation are exacerbated and given a patina of complexity with the emerging geoeconomic competition that is taking place across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) between China, India, and Japan, and to a lesser extent South Korea, Turkey, Iran, Russia, European Union, and the United States. This geoeconomic competition is manifested primarily through infrastructure across the Eurasian landmass and the IOR, not just in terms of highways, railroads, pipelines, ports, and electrical grids, but also submarine and fiber-optic cabling, routing and data centres, and satellites and significant space programmes involving everything ranging from human spaceflight and space stations, to placing scientific probes on the Moon and Mars, and even human colonies.

In both the classical geopolitical competition between the Great Powers (United States, China, Russia, India, Japan, and the European Union) and the geoeconomic-infrastructure competition, space power – the ability in peace, crisis, and war to exert prompt influence to, in, and from space – is both a critical enabler, source of competition, and possibly a domain in which warfare might be conducted.

Space power is now a tool of geopolitical and geoeconomic competition much like navies and merchant marines, and given the expense and engineering sophistication involved, space power is also representative of the economic and political models that wield it, whether it be the free market liberal model of the United States and Europe, the state-owned enterprise model of China and Russia, or the hybrid approaches preferred by India and Japan.

In that sense, it might be said that the Great Power able to field and sustain a full panoply of space power (space launch, satellite communications, Earth observation, environmental monitoring, and positioning, navigation, and timing) along with significant achievements in space exploration in the face of its competitors, has the superior economic and political model that other countries would want to emulate.

India finds itself – geographically, diplomatically, economically, and militarily – at the centre of this geopolitical and geoeconomic competition, and while it must deploy and sustain its traditional instruments of power to a satisfactory – albeit challenging – level of strategic performance, Indian space power could provide it with a critical competitive edge in terms of both hard and soft power. I’ll return to this theme later.

China, perhaps India’s greatest and most dangerous geopolitical and geoeconomic rival, also uses space power to great strategic effect, primarily aimed at countering the United States, still the world’s preeminent space power for the foreseeable future. For China, space power is not only important in terms of satellites, launch, and space exploration, but also as a means for projecting power into its periphery (on which India finds itself) and to deny the United States military access to the Western Pacific.

In this sense, Chinese space power plays a critical role in the kill chain of its ballistic and cruise missile capabilities, naval and amphibious forces, and for the command and control and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support for its expanding long-range air power. Much like in the United States and its closest allies, Chinese strategic thinking also posits that its space power can only function adequately in crisis and war if it is able to, at the very least, deny its adversaries the ability to use the space domain for their own ends. It is for this purpose that China is developing its counterspace capabilities, posing a threat not just to U.S. space power, but also to the space power of India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, and others across the region, in the event of war.

China’s desire to keep the United States out of the Western Pacific, solidify its claims over the South and East China Seas, deny India supremacy over the Indian Ocean as well as develop the means to access the Indian Ocean from Pakistan and potentially Myanmar, as well as balance Russia and be able to access the receding Arctic waters to the North, all create potential flash points with a range of countries that could well involve warfare in space.

This counterspace threat, while real, should also be put into a wider strategic perspective. China’s economic and military reliance on space grown with each passing year, making space warfare a costly prospect for Chinese strategic planners and businesses. China’s economy and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) all require growing space-based connectivity, geospatial data, and positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) services that would all come under imminent threat from U.S. and allied counterspace capabilities should war breakout.[i]

Indian strategic planners should take the prospect of space warfare with China seriously, and seek out – initially at least – the most effective passive protection technologies and tactics for Indian space power, such as hardening of satellites, disaggregated constellations, and smaller satellites that can be more readily replenished, as well as increased integration with terrestrial Indian military forces to dissuade Chinese planners from thinking that they can easily knock out Indian satellites without involving Indian land-, sea-, and air power.

But while such preparations will be necessary to dissuade Chinese temptations to conduct preemptive warfare in space, they are hardly sufficient to channel Great Power competition between India and China in space into a less dangerous and potentially more productive direction.

As China seeks to expand its influence through the BRI, and its space-based equivalent, so India should look to do something similar through its Look East Policy, as well as through its nascent and unofficial Look West initiative. In many respects, India is already doing this through recent space cooperation agreements with ASEAN, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates among others, but it can do more along the following lines:

- Make space cooperation a cornerstone of its science and technology engagement strategy in India’s Look East Policy and its unofficial Look West analog. This space cooperation should utilize the soft and reputational power of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) as a vehicle for creating a community of like-minded space powers across the Indian Ocean Region from East Africa to Australasia and all points in between. This community of Indian-centric space powers can provide the basis for a norms-building effort in space, provide a form of collective security in space (thus complicating Chinese counterspace targeting), as well as provide a range of economic, social, and environmental benefits to all involved.

- Take on more of a leadership role in space diplomacy, especially in the effort to delegitimise Chinese military space doctrine, develop and encourage strong norms of behaviour in space among all users of the domain, and to shape a more transparent, substantive, and less cynical space arms control agenda in international forums, thus at least delaying Chinese counterspace development and deployments, and even perhaps denting it through diplomatic means.

- In partnership with the United States, Japan, and Australia, develop a fundamental space infrastructure that can be used by all like-minded space powers across the IOR. This infrastructure could include not only space launch and tracking and telemetry facilities, but also a space situational awareness (SSA) network that provides a measure of transparency on Chinese military space activities, as well as a space-based strategic early warning network and the protection of all partner PNT resources.

- In partnership with U.S., Japanese, and other friendly space agencies, lead and participate in space exploration and scientific missions that not only temporarily increase prestige, but build a soft power reputation over the long term that adds substantively to human knowledge and discovery. Being first in space certainly captures the headlines, but staying in space requires something more and produces greater benefits across the board. India is already doing this, but should perhaps emphasize this aspect of its space programme more in order to entice long term partners from across the IOR at the expense of China.

- Unleash Indian ingenuity, innovation, and entrepreneurship in space by empowering the Indian NewSpace sector. If Indian space has one weakness, it is its poor commercial track record in space to date due to over-regulation and a sclerotic approach to the commercialization of space. This can be changed without destroying what makes ISRO special and useful, primarily through a more rigorous policy definition of what it is ISRO must do for Indian national interests such as the provision of basic strategic space services, and then deregulate all other activities and ancillary sectors to empower India’s private sector. It is here that India could potentially wipe the floor with its Chinese competition, and force Beijing to devote more of its resources in this direction just in order to keep up.

Obviously, space is but one facet of Great Power geopolitical and geoeconomic competition, but in the 21st Century it is likely to become a critical factor in international politics as both a hard and soft power tool.

A country’s space power performance is a window into its political and economic system, hopes, and aspirations, and India’s space power has much to offer and potentially more. Engaging in an action-reaction, tit-for-tat, competition with the Chinese counterspace programme is likely a losing and futile proposition that will not play to Indian strengths nor do much to mitigate the security dilemma that Chinese counterspace poses. Any least for now, India should avoid deploying its own counterspace capabilities, and instead focus on more cost- and security-effective passive protection measures for its military space capabilities, along with more integration of space forces into its conventional military force structure.

Instead, the most strategically salient approach to deal with Chinese counterspace capabilities is to render them irrelevant to the space power competition by placing India at the heart of an IOR community of like-minded space powers that share a common infrastructure and space assets, that establish a viable and attractive set of norms of behaviour in space, and that raises the economic tide for India and its friends through a vibrant and prosperous NewSpace economy that showcases Indian innovation and entrepreneurship, and exposes the inadequacies of Chinese approaches to space power.

The challenge for Indian government and businesses will not be ideas or the will to compete, but to sustain a level of strategic performance viz-a-vis that of Chinese strategic performance over a long period of time, while demonstrating prudence and wisdom in its affairs of state in an increasingly dangerous world.

[i] It should be noted that if war broke out between nuclear-armed Great Powers, space warfare would be the least of our concerns.

Dr. John B. Sheldon is the Chairman and President of ThorGroup GmbH, and publisher of SpaceWatch.Global