By Christophe Bosquillon

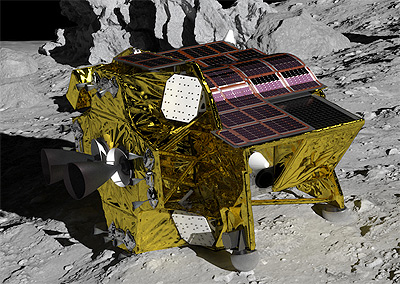

The JAXA SLIM (Smart Lander for Investigating Moon) mission soft-landed on the Moon on the night of Friday 18 to Saturday 19 January 2024 Japan Standard Time. JAXA would eventually confirm a successful precision landing for SLIM a few hours later. SLIM landed, but had an “attitude problem,” its position preventing its solar cells from receiving proper illumination. After completing operations from January 30th to 31st, SLIM entered a two-week dormancy period. Although SLIM was not designed for the cold lunar night, JAXA intends to try to operate again from mid-February, when the Sun will shine again on SLIM’s solar cells. Can we call the SLIM mission a success, or not?

SOFT LANDING?

JAXA provided a self-assessment of the mission immediately after the landing, and gave itself a 60% success rate. It wasn’t simply a technical assessment, it was a diplomatic dilemma: technically, SLIM did soft-land, which indeed made Japan the 5th country to do so on the Moon. This fact was internationally acclaimed. But in the moment, it felt more like an awkwardly silent achievement than your traditional mission control room cheerful explosion. Especially if you understand enough endless iterations of familiar Japanese expressions (such as “shibaraku o machi kudasaï” (please wait a moment) and “kakunin chū” (being in the process of confirming status)) to sense that something isn’t quite where it should be.

It’s up to human ingenuity to salvage a seemingly compromised mission.

This felt like déjà vu of the ispace Hakuto-R mission 1: it achieved self-charted “successes 1 to 8” but fell short of completing “success 9”, which was soft-landing. In that case, had success 9 been realized, it would have been followed by “success 10” to achieve successful deployment of payload on the lunar surface. Whereas JAXA SLIM, contrary to Hakuto-R mission 1, achieved soft and precise enough landing, and released small robots as planned, it encountered other problems.

It might be easier to understand where the “success” lies if we refer to JAXA’s own defined “success map”, together with the SLIM mission’s objectives and the criteria for such “success.”

SLIM is a JAXA project aiming to contribute to future lunar and planetary exploration by achieving the following two objectives:

- Objective A: demonstration of high-precision landing technology on the Moon, that aims at landing accuracy of 100 meters compared to several kilometres to tens of kilometres of conventional lunar landers. Key technology includes “Vision-based navigation” and “Navigation, guidance and control.”

- Objective B: realization of a lightweight lunar and planetary probe system to allow more frequent lunar and planetary exploration missions. A small, lightweight, and high-performance chemical propulsion system, combined with weight reduction of core elements in most spacecraft such as computers and power supply systems.

Based on the above objectives A and B, degrees of success and success criteria for the SLIM project are defined as follows.

Minimum success: to realize a soft landing on the Moon with a small and lightweight spacecraft, by accomplishing the following two items: conducting an actual lunar landing descent and verifying the vision-based navigation, which is essential for high-precision landing; developing a lightweight spacecraft system and check its operation in orbit.

Full success: to achieve high-precision landing within 100 meters accuracy. For that, the navigation system and the guidance rules must operate normally, and the achievement of landing accuracy must be confirmed by telemetry data after landing.

Extra success: continue activities on the lunar surface for a certain period of time until sunset. That includes carrying out missions that operate on the lunar surface to obtain knowledge for lunar and planetary surface exploration in the future.

Technically, SLIM did soft-land, which indeed made Japan the 5th country to do so on the Moon.

Following an early report in Nature JAXA did indeed confirm the good news: the telemetry data showed that SLIM did land within 100 metres of its target zone, thus pioneering its new image-based automatic navigation system. This is a big deal and indeed fulfils the above criteria for “full success” which was somewhat lost in translation due to the hiatus between the live landing and the ensuing press conference. Later, solar cells did catch some sun and SLIM managed to pursue operations before shutting off for the 2 weeks lunar night.

The lesson learned from JAXA is that there is a need to be much more specific and “segmented” in the way to define mission objectives, milestones, benchmarks, and criteria that sanction fullfilment. As government and private sector cooperation is on the rise, and as we see more commercial relationships, as in hosting third party payloads on a mission, there is a need to define such objectives and criteria for contractual and financial settlements.

For mission crews, there is an evident need to put on a brave face and a positive spin when the chain of events doesn’t unfold as planned. It is also a responsibility of leadership to be as transparent as possible while communicating the facts as they pop up, and to navigate the drama of attempts at saving the mission. Without a shadow of doubt, some missions will be setting a standard, or at least a strong precedent, in that domain.

GEOPOLITICAL SUCCESS

The US and the Former Soviet Union were the first countries to manage to get a lander on the Moon without damage, followed by the Apollo era during which the US only set the standards of Moon exploration. After, nothing happened for almost 40 years. Then 2013 arrived, and it changed everything: after sending a spacecraft to orbit the Moon in 2007 and again in 2010, China landed the Chang’e-3 spacecraft in 2013. In 2023, India successfully landed Chandrayaan-3, with perfect timing providing an entire nation and PM Modi with a triumphal moment at the BRICS summit (this together with an invitation to BRICS countries to join forces in space). In 2024 Japan became the 5th country to land “successfully” on the Moon. Indeed, 2013-2024 will have been a great decade for the Indo-Pacific region, and this is only the beginning. As for Japan, there is room for a new definition of geopolitical success by combining the strengths of government (JAXA) and the private sector (ispace et al.).

Japan’s JAXA SLIM mission exemplifies the challenges and complexities in lunar exploration, where even a seemingly successful landing can face unexpected issues. But perhaps one of the most compelling aspects is that everyone starts to slowly understand the nature of lunar exploration: there are many challenges, first to get there. Then to land there, and then to deploy. On the other hand, a mission that seems doomed can be salvaged to a certain extent. The sun does move around. Batteries can be reloaded. It’s up to human ingenuity to salvage a seemingly compromised mission that can still be made to succeed in crucial aspects. That bears consequences on all aspects of a mission, commercial, financial, and human.

This is what we humans do best: when challenged, we improvise, adapt, overcome, and move forward before the lunar night puts us to rest. Or at least this is what we’d like to believe. But if we didn’t believe, we wouldn’t, after all, be human.

Christophe Bosquillon has a diverse professional background, having operated globally with a focus on the Indo-Pacific region. His experiences in Japan, the Koreas, Taiwan, China, ASEAN, India, Russia, and Australia have given him a deep understanding of the multipolar realpolitik of our world under the Pax Americana. With a background in engineering, trade, and foreign direct investment in industries relevant to Space Resource Utilization (SRU), such as mining, transportation, energy, manufacturing, agrifood, environment, and digitalization, Chris is committed to developing SRU value chains that benefit the Earth. As an executive, owner, writer, and founder of Autonomous Space Futures Ltd, Chris has extensive experience in collaborative policy crafting and works to develop space business and governance models relevant to society. He is a member of NGOs that provide input to the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) legal subcommittee Working Group on Space Resources. Chris contributes to regulatory clarity on appropriation, priority, sustainability, and sharing in a way that balances national interests with civil society inclusion, provided a transparent due process is followed. When advocating for access to technology and space for the Global South, Chris believes that emerging space powers’ participation in space markets must be commensurate with their interest and involvement in international space politics. He believes that their ability to develop sovereign domestic capabilities with spillover potential is also essential. Chris is keen on ‘Peace Through Strength’ diplomacy and deterrence-based security as enablers of secure space access. He supports sovereign cislunar space situational awareness as mandatory for freedom of circulation in the space domain and deconflicted cooperation on the Moon