by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 10 – 16 January 2022 ”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 10 – 16 January 2022 ”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Space News Roundup! I’m Jean Deville, joined as always by my co-host Blaine Curcio. This week, we discuss a retrospective research article on Chinese commercial space funding rounds in 2021, but first let’s get into the details of how the Chinese space station manages risks of collision with space debris, and the safety of taikonauts.

1) How does China manage the risk of orbital debris for the Chinese Space Station?

Jean’s Take

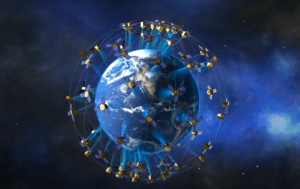

The Earth’s orbit is littered with space debris, consisting notably of rocket upper stages and of decommissioned satellites, and this poses increasing risks for satellites in operation, and perhaps even more to astronauts working on space stations in LEO. The topic has grown even hotter recently,  with Indian and Russian ASAT tests in recent years, as well as two Starlink satellite maneuvers that have allegedly forced China to take collision avoidance control to avoid any risk of collisions.

with Indian and Russian ASAT tests in recent years, as well as two Starlink satellite maneuvers that have allegedly forced China to take collision avoidance control to avoid any risk of collisions.

This is a good opportunity to talk about China’s collision avoidance strategy on the Chinese Space Station, and this is based on details revealed last week by Hou Yongchun, the deputy chief engineer of the Chinese Space Station’s systems (and notably life support systems).

The Chinese Space Station has a 4-level approach to protect its taikonauts against catastrophic collisions, called 防躲堵逃 or: protection, avoidance, repair, and escape:

- The first two strategies are fairly classical stuff: for very small debris or micrometeorites, the Chinese space station is designed to resist the impact, with notably the walls of the different modules being strongly reinforced. This is 防.

For larger debris or other satellites, the Chinese Space Station adopts avoidance maneuvers to change orbits and avoid collision trajectories, and this is typically what was done vis-à-vis two Starlink satellites a couple of weeks ago. This is 躲.

Where it gets interesting are the next two:

- Let’s say the Chinese Space Station gets hit by debris which manages to dent and to punch a tiny hole in the space station. The Chinese Space Station is fitted with acoustic sensors all over the walls, and it uses the acoustic waves emitted by the impacts to roughly locate the leak, convey the information to the taikonauts, which then use hand-held (acoustic) instruments to locate the leak more precisely. And finally, once this is done, the taikonauts are provided with a number of patches that they apply on the holes, and are able to mitigate holes up to 20 mm in diameter. This is 堵.

- Beyond that, if the damage is too serious, then the last solution is to escape, or 逃. As the pressure in the space station drops due to the leak, the station is equipped with emergency pump systems which drive the pressure back up sufficiently to buy enough time for the taikonauts to make it to the Shenzhou spacecraft, abandon the station and return to Earth.

Another interesting story on the evacuation of the Chinese space station that most people aren’t necessarily aware of, is that there is an emergency Long March 2F carrying a spare Shenzhou spacecraft, at the Jiuquan Launch Center, on standby. The idea is that if the Shenzhou spacecraft docked to the space station has an issue of any kind, the spare Long March 2F will launch to deliver an operational Shenzhou to the taikonauts in space.

Overall, debris is becoming an increasing problem for satellites in LEO and for human spaceflight. There is a need for more regulation to keep things from worsening in the coming years, and there may be a need to clean the orbit of some of the existing space waste. There are some commercial companies that believe that there is a business case for debris removal services, such as Japan-based company Astroscale, and we are starting to see a similar phenomenon in China. A young Chinese startup called Origin Space (起源太空), founded in 2019, is planning to develop orbital debris removal services, among other things, and launched one such demonstrator in April 2021, the NEO-1 satellite.

And speaking of a young ambitious startup, this is a nice segue to the topic of how Chinese startups have been doing for the past year. Blaine, do you want to fill us in on that?

2) Qichacha Publishes Chinese Commercial Space 2021 Review

Blaine’s Take

This week, Chinese company database Qichacha published a review of Chinese commercial space funding in 2021. Before digging into the report, a little bit of context. The report was published as part of a series from Qichacha Data Research Institute (企查查数据研究院) that was done in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China, basically looking at different industries that have flourished in recent years (including space), and loosely tying their economic success to the party.

That being the case, it is perhaps unsurprising that the report starts with a timeline of China’s traditional space achievements, starting with the launch of the Dongfanghong-1 satellite (东方红一号)on 24 April, 1970 (China Space Day). Other events that made the cut on the timeline include the first Shenzhou mission (2003), the Chang’e missions, Tianwen, and the recent 400th launch of the Long March.

After the initial obligatory credit being given to the traditional space sector, the Qichacha report digs into the aerospace and space sectors in a lot of detail. Definitionally, the report is quite broad: Qichacha notes that they currently count 95,000 aerospace companies in China, so we believe this would also count various aviation verticals, and could include startups in industries as diverse as drones, airplane engines, and advanced materials.

After the initial obligatory credit being given to the traditional space sector, the Qichacha report digs into the aerospace and space sectors in a lot of detail. Definitionally, the report is quite broad: Qichacha notes that they currently count 95,000 aerospace companies in China, so we believe this would also count various aviation verticals, and could include startups in industries as diverse as drones, airplane engines, and advanced materials.

That being said, in terms of statistics for commercial space specifically, Qichacha reported 35 funding rounds for Chinese commercial space companies in 2021, totaling RMB 6.45B. This was down from last year’s absolutely huge 42 funding rounds and RMB 9.76B of funding, but remains by far the 2nd-largest year in Chinese commercial space in terms of funding, with >2x the 3rd-best year (2018). 2021’s average round size was RMB 184M, down from around RMB 232M in 2020, but still second-best of any year by far. Of the 35 rounds, 19 were seed, angel, or A rounds, accounting for 54% of funding, with this a change from the past couple of years, when most funding rounds were relatively later stage. Last point is that as recently as 2013, funding was zero, and even as recently as 2015, funding was only RMB 60M, or about US$9M.

When we compare these high-level figures to the Euroconsult China Space Industry Quarterly, Q4, which totals all 2021 funding rounds, we find that the Euroconsult study tracks considerably more funding rounds (50 in 2021), but a roughly comparable figure for funds raised, indicating (probably) more conservative estimates by Euroconsult compared to Qichacha.

The article concludes with a table of commercial space funding rounds in 2021. We’re happy to say that we’ve reported on the majority of the rounds included, but we also note that their list is not exhaustive–for example, they include a May 2021 funding round from maritime satcom service provider Sky Sea World, but do not include a November 2021 funding round from maritime satcom service provider Ningbo Ditel. We also note the apparent absence of a July 2021 funding round from satcom terminal manufacturer Starwin. Either way, a solid representation of Chinese commercial space funding rounds in 2021, and a really interesting historical perspective on some of the data.

One of the fun things about these articles is that you inevitably find out about a few Chinese commercial space companies that you’d never heard of, and this year was no exception. Among others, we out 小眼探索, a maker of chips focused on edge computing, 微动时空, a company focused on solar array drive assemblies, and 星空动力, building hall-effect thrusters. Last point: these three companies (among others) are but the latest instance of the increasing number of subsystems-level satellite manufacturers, which we also discussed in last week’s Dongfang Hour when reporting on HiStarlink.

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space