By Dr. Deganit Paikowsky

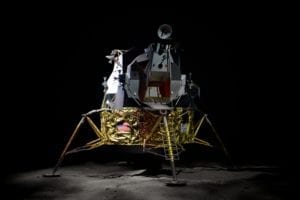

Last week, NASA released “The Artemis Accords: Principles for a Safe, Peaceful and Prosperous Future.” The aim of the Artemis program, according to NASA, is to “[L]and the first woman and the next man on the Moon by 2024, heralding in a new era for space exploration and utilization”. I read the short, concise document that NASA published with a great deal of interest, and a number of thoughts about international technology, economics, and politics came to mind.

But first, in a nutshell, the Artemis Accords: “While NASA is leading the Artemis program, international partnerships will play a key role in achieving a sustainable and robust presence on the Moon while preparing to conduct a historic crewed mission to Mars. With numerous countries and private sector players conducting missions and operations in cislunar space, it’s critical to establish a common set of principles to govern the civil exploration and use of outer space. International space agencies that join NASA in the Artemis program will do so by executing bilateral Artemis Accords agreements, which will describe a shared vision for principles, grounded in the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, to create a safe and transparent environment which facilitates exploration, science, and commercial activities for all of humanity to enjoy.”

The Artemis Accords are meant to provide an overall shared perspective and structure for activities on the moon. Where germane, the Accords rely on existing treaties, agreements and conventions. It’s important to mention that the Moon Agreement, i.e. Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, which the U.S. has not signed, is not mentioned in the Accords at all. In fact, the Artemis Accords constitute a replacement arrangement, to bypass the Moon Agreement. The Accords include ten principles guiding the program, which serve as the basis for the activities that the partnerships will carry out under its umbrella:

- All activities will be conducted for Peaceful Purposes.

- Transparency regarding space plans and policies.

- Interoperability of operating systems; in utilizing open international standards; and in developing new standards.

- Emergency Assistance.

- Registration of Space Objects.

- Public Release of Scientific Data acquired during the program.

- Protecting historic sites and artifacts.

- Extracting and utilizing Space Resources will be permitted.

- Deconfliction of Space Activities, by creating safety zones.

- Preventing and dealing with Orbital Debris and Spacecraft Disposal, pursuant to the principles of the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the UN-COPUOS.

Below are some of my thoughts on several of these principles.

The US is Fortifying its Status as “The Club’s Gatekeeper” – Space programs are very expensive and complex projects, with a high degree of risk. Furthermore, crewed spaceflights, like the historic Apollo flights, and now the Artemis program, do not provide direct economic or security benefits. Thus, the investment in them is not self-evident. Nor is exploration at the top of any country’s agenda. So how can an investment of this magnitude be explained? The key to understanding these processes is in identifying the political incentive.

The moon has always held an important place in human culture. But it was the conflict between the superpowers during the Cold War that turned the moon into a significant political objective, in terms of power, status and influence. Even today, countries that see themselves as world powers aim for the moon. China, Russia, India, Europe and other countries are trying to reach the moon, either with crewed flights or with technological missions. The Artemis program makes the moon a political objective. In this context, the Artemis Accords are meant to send a clear message that the Americans are leading in the race for world technological-political superiority.

“It’s the economy, stupid” – From a political, technological and scientific perspective, establishing a base on the moon and exploiting its resources are touted as a stepping-stone to sending a crewed flight to Mars at some future date. But turning the moon into a source of resources has its own weighty economic significance and value, which the Artemis Accords seeks to maximize. As early as 2015, the US began to pass laws permitting the extraction of material from space resources. Luxembourg followed suit in 2018. The present process is designed to establish regulation of such licenses. There’s a message here for the private sector, and for all the entrepreneurs who dream of partaking in the growing space economy: deepen the knowledge and technology required to fulfill that dream.

Regulation isn’t a dirty word – Following this last point, the message to the private space sector in the US is that the government views having a strong private space sector as very important to the country’s future power and world leadership, and is willing to help promote private initiatives. In the tapestry of interwoven relationships between the government and the private sector, one of the government’s important roles is to promote an ecosystem of innovation and leadership. In order to do so, it provides a structure of clear and transparent rules and regulations, which enables the private market to plan, operate and cooperate. Publishing the Artemis Accords is another stage in the process of creating a regulatory framework for developing a complete ecosystem of products and services, based on agreed-upon standards. This step provides an advantage to American companies: the government’s backing will help them attract investors to a developing field which carries high risk and entails many uncertainties.

“I did it my way” – In the opening sentences of the Artemis Accords, NASA emphasizes that it is leading the program, and that its international partners have a key role to play in achieving the program’s goals. The traditional approach of the US to establishing a partnership in the field of civil space is reflected in these words; the US, via NASA, sets the dominant tone. Since the Artemis Accords were published, they’ve been subject to international criticism on this point: they express one-sided American management. That stands out, especially given the fact that the subject has been on the world’s agenda, with the aim of drawing up multi-lateral agreements. Thus, the Artemis Accords again emphasize the strength and ability of a superpower to impose its will by establishing the field of action, the rules of the game, and the agenda.

In light of the increasing tensions between the powers in recent years, it is unsurprising that the position of the United States engenders a great deal of opposition by Russia and China. In trying to evaluate how the present American policies will be received internationally, we should look at the natural partners of the U.S. in processes such as these. The US’s allies, primarily in Europe, see the American approach as a challenge.

Follow the money to 2024? – This is not the first time that the US has set a goal of reaching the moon, and from there, Mars. The George W. Bush Administration set similar objectives for the Constellation program. In the absence of sufficient appropriations, the financial crisis of 2008, and a new president, the program was cancelled. The message is that the budgets directed toward fulfilling the policies are no less important than statements and documents like the one before us. The first crewed mission of the Artemis program is planned to launch in 2024. Under present conditions it’s very doubtful that that schedule will be met.

The Israeli perspective– At the end of 2009, the Israeli space industry was in real crisis. The then President, the late Shimon Peres, established a task force of experts to propose ways of strengthening it. The task force was led by the Chair of the Israel Space Agency, Professor Isaac Ben-Israel; and the then General Director of the Ministry of Science, Menachem Greenblum. Representatives from all of the relevant R&D entities took part (full disclosure: I had the honor of staffing the task force, along with Ram Levy). The task force’s principal conclusions called for establishing a civilian space plan for Israel, with a fairly small annual budget of 300 million NIS for a period of five years. The Space Agency of the Ministry of Science and Technology is working to fulfill the recommendations. The fact that it only received part of the recommended budget limited its ability to completely implement the task force’s recommendations, and the results are therefore, not satisfactory. The State Comptroller’s report of 2018 refers to this at greater length.

The Israeli space industry and academia are among the world’s leaders in quality of outcomes. However, the small local market, the absence of a multi-year plan backed by appropriate financing, and an unstable regulatory structure, prevents the existing creative Israeli space community from blossoming. Last year, in an effort perceived as national, the non-governmental Beresheet mission reached the moon. Although the effort wasn’t completely successful, it achieved most of its objectives. Beresheet was seen as a trailblazing project for other private missions around the world, encouraging them to literally “aim for the moon” in the future.

The Israel Space Agency is taking part in the Artemis program. During the first stage, Israel is partnering with NASA and the DLR to test the vests developed by the Israeli StemRad company, which are designed to protect astronauts from radiation. Currently, Israel examines the possibilities for expanding its participation in Artemis.

At present, the Israel Space Agency is completing a strategic evaluation process regarding the maintenance and reinforcement of Israel’s civilian space capabilities and assets. I participated in that process as an external expert. Developing an ecosystem for the field of Israeli civilian space, including significant international cooperation, will enable the local space industry and academia to become part of the world’s spearhead in this field. Moreover, it will constitute a lever for innovation and technological leadership for all of Israel. Noteworthy, too, is that Israelis’ tremendous interest in the Beresheet mission proved that the Israeli public is thirsty for inspiring projects. Required to achieve this are: vision, resources, materials, and a conceptual framework to organize civilian and commercial space activities. We lack all of these components today, but that can be changed. International cooperation should be deepened and private companies nurtured. At the same time, Israel should move forward on promulgating clear and transparent regulations, by passing a Space Law that will provide the appropriate structure and standards, to enable private companies to actively function in the space market.

Dr. Deganit Paikowsky is a Non-resident Scholar at the Space Policy Institute, George Washington University, a VP at the International Astronautical Federation, and the Author of “The Power of the Space Club”, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space