By John B. Sheldon

More than fifty years after the first Apollo Moon landings, we are witnessing the rise of Lunapolitics, where the Moon’s topography – or ‘Lunography’ – from below its surface through to Cislunar space intersects with Earthly political and economic interests.

If we manage Lunapolitics sensibly then our eventual permanent presence on and around the Moon – as well as our exploitation of its resources – will be relatively benign, peaceful, and even sustainable. If we get Lunapolitics right, people can benefit from new economic opportunities, advances in scientific knowledge, and the opening of a space exploration and commercial gateway to the rest of the Solar System.

If we get it wrong, however, it is likely that instead of managing stable and predictable, if occasionally challenging, Lunapolitics we will likely have to endure an intolerable Lunapolitik, an off-world approximation of Karl Haushofer’s Geopolitik which inspired Nazi Germany’s violent geopolitical expansionism.

Until now, Lunapolitics has literally been the stuff of science fiction as depicted in novels by, for example, Robert Heinlein and Ian McDonald, or movies such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and the more recent Ad Astra. Even during the height of the Cold War, when the United States landed Apollo astronauts on the Moon the locus of the strategic competition for ideological supremacy with the Soviet Union remained back here on Earth, even though the rivalry extended to space.

Today, Lunapolitics is rising because the Moon is the object of growing international and commercial competition, rather than being just the incidental location of a war of ideas as it was in the past.

In fact, a number of developments to do with our presence on and around the Moon are in play today. If they are even moderately successful, they will make Lunapolitics – the lunar corollary of geopolitics – a permanent reality by the end of this decade.

These developments include a converging competition for the Moon primarily between the United States and China, with both countries trying to woo other space powers to their side. These other powers include Russia, Europe (through the European Space Agency), India, and Japan, among others.

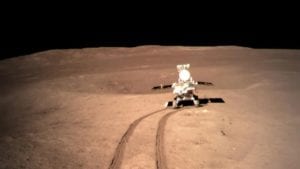

China’s impressive Chang’e lunar exploration programme – which includes contributions from European and Middle Eastern space powers – is expected to be completed with a Chinese crew making a landing at the Moon’s South Pole, where scientists expect to find some of the biggest deposits of ice, which could then be harvested for water, oxygen, and fuel. Additionally, China’s Queqiao (‘Magpie Bridge’) communications relay satellite is in a halo orbit around the Earth-Moon Lagrange point L2 – a potential strategic chokepoint in Lunpolitics.

For its part, the United States has, of course, already landed a dozen human beings on the lunar surface, one of the greatest and most inspiring human achievements in history. But it is not content to end things there. Instead, the US has set itself the ambitious goal of returning Americans to the Moon by 2024.

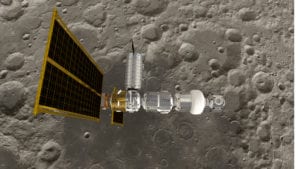

The US is also leading a multi-billion dollar international effort involving the European Space Agency, Canada, and Japan to build the Lunar Gateway space station that will be placed in a halo orbit around the Moon and its Lagrange points, which are potential strategic chokepoints in Lunapolitics. Additionally, the US military is commissioning studies from commercial vendors on how to conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations in Cislunar space and on the Moon’s surface.

Lunapolitics is not just about great power competition, cooperation, and positioning over the Moon and its strategic chokepoints. It is also an economic competition – Lunaeconomics played out over the Moon’s resources, involving private and state-backed corporations.

After the demise of Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries over the past several years, a second generation of companies is vying to exploit resources on the Moon and other celestial bodies such as comets and asteroids.

Unlike the first generation of space resources companies that were exclusively American, this second generation includes a larger number of firms from other countries, such as China, Japan, Australia, Germany, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, as well as the United States.

This international field is, in turn, exerting influence on their respective governments and their longstanding policy assumptions regarding the legal and diplomatic status of the Moon and space resource extraction in general.

Some countries, such as Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States, have already created legal, regulatory, and policy instruments that essentially recognise the Moon as a place for economic – and, implicitly, political – competition.

For example, on 6 April 2020, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order on ‘Encouraging International Support for the Recovery and Use of Space Resources’ that calls for a significant US diplomatic effort to create a community of like-minded countries to establish the necessary norms and governance for exploiting space resources on the Moon and elsewhere, as soon as it is technologically feasible to do so. The executive order also calls for a rejection of the 1979 Moon Agreement and the notion that space is a global commons.

The executive order has sparked a fierce international debate – much of it taking place here on SpaceWatch.Global – and it is an indication that the current diplomatic and legal arrangements governing commercial space activities relating to space resource extraction, as well as the status of the Moon and other celestial bodies, might yet be disrupted.

The fact that the executive order has sparked such a debate among diplomats and lawyers is itself an indication of the coming rise of Lunapolitics. If the issue were truly regarded as unimportant and irrelevant, then diplomats would not expend so much political capital, nor lawyers rack up so many expensive billable hours.

These developments are the foundation for the rise of Lunapolitics – but only if they are handled responsibly and in a self-enlightened manner by all involved.

This means that the primary players in the growing competition for the Moon, primarily the United States and China but also the other space powers, should engage immediately in good-faith discussions about the governance of all space resource extraction activities on the Moon (as well as elsewhere), with the aim of finding a compromise to end current controversies, such as the relevance of the 1979 Moon Agreement – an agreement that only 18 countries have signed and ratified.

These discussions should cover such issues as the right and freedom of passage through and on the Moon’s strategic chokepoints such as the lunar poles and the Lagrange points in Cislunar space, the recognition of claims, legal protections, and arbitration arrangements for lunar sites where resources are to be extracted, as well as long-term principles that ensure sustainable and responsible activity in, on, and around the Moon.

The recently announced Artemis Accords may provide the basis for such discussions, but this will depend not just on what these accords propose, but also on the international reaction to them. The US should use the Artemis Accords as just one basis for negotiation with other countries, and not use them as part of a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ agenda. Similarly, a rejection of the accords by other countries simply because they are a US idea, or because of a political aversion to President Trump, will be just as short-sighted.

Failure to engage in such discussions and to scorn good-faith compromise based on narrow ideological and short-term interests is to invite the worst-case scenario — the rise of Lunapolitik.

In Lunapolitik, rival countries adopt a zero-sum approach to their competition with each other, occupying and reoccupying instead of sharing strategic or economically valuable locations on and around the Moon. Such an eventuality will make the overt militarization of competition for the Moon all but inevitable.

Furthermore, a Lunapolitik scenario would encourage mercantilist competition for the Moon’s resources, that in turn could create the conditions for commercial raiding and private military contractors, and all of the political and economic costs and risks that would come with all that. Think of the Moon as depicted in the 2019 Brad Pitt movie Ad Astra, but on steroids.

A Lunapolitik scenario will be in the interests of no one, and so the current players in the rise of Lunapolitics have a stark choice in front of them. Create a diplomatic and governance framework that encourages healthy (and necessary) competition for the Moon and its resources, and allows all who can get there to participate in that competition, or, preside over a catastrophic, expensive, and zero-sum scrap that will make our first significant permanent foray into space a benighted one for all time.

The choice is ours. A Lunapolitik scenario does not have to be inevitable even if geopolitical realities today can make compromise difficult. If diplomats can keep their eyes on the future of the Moon and its potential for all humankind, as well as on the political and economic interests of their respective governments today, we might just come up with something workable and durable.

Lunapolitics doesn’t have to be pretty, it just has to do the job of maintaining stability and bounding competition. That is a worthwhile endeavour.

Dr. John B. Sheldon is the publisher of SpaceWatch.Global and Chairman and President of ThorGroup GmbH.