Katarina Miljkovic, Curtin University

We’ve all heard of earthquakes, but what about marsquakes?

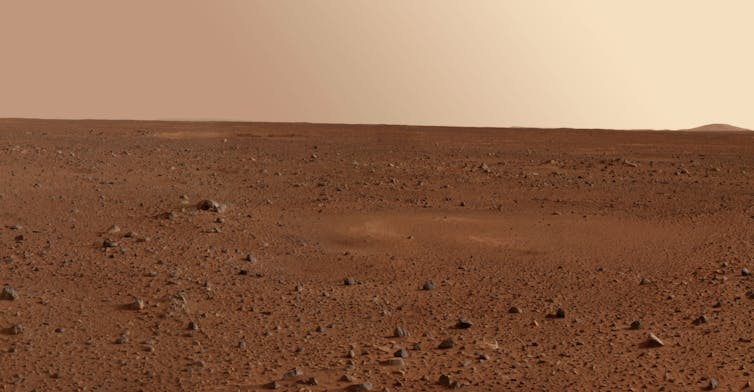

NASA’s InSight mission has, for the first time, recorded seismic activity coming from Mars’ interior. The observations, recorded in 2019 and published today, will help understand the red planet’s internal structure, composition and dynamics. It opens a new chapter in planetary geophysics and exploration.

The NASA InSight mission has been operating on Mars since November 27, 2018. Soon after its seismic instruments were deployed in February 2019, InSight began detecting quakes and shakes. By September 2019 the InSight team had detected 174 marsquakes, and the total number continues to grow on a daily basis.

What kind of quakes were detected on Mars?

The recorded quakes fall into two distinct categories: 150 small ones, with high-frequency vibrations that suggest they occurred within the planet’s crust, and 24 low-frequency events which probably took place at varying depths beneath the crust. Small events are more frequent than the large ones, which is also common for the Earth.

The two largest events probably originated from the Cerberus Fossae fracture system, a young tectonically active region about 1,600 kilometres east of the InSight lander’s position. These two largest events were between magnitudes 3 and 4. This means that if they had happened on Earth, they could have been big enough to cause minor damage to structures. About 30,000 earthquakes of this magnitude are typically detected on our planet each year.

Because the characteristics of marsquakes change according to the nature of the material through which they pass, we use these recordings to begin to learn about Mars’s interior structure. For example, the speed of seismic waves changes with the material density, hence it can be used to mark the boundary between a planet’s crust and the mantle beneath.

Quake-hunting heritage

The InSight mission has become the first to detect quakes coming from the interior of another planet. However, it wasn’t the first to spot quakes on an extraterrestrial world. The Moon hosted a network of seismic sensors, deployed over the course of three years, beginning with the Apollo 12 mission in 1969. The network successfully detected many moonquakes until it was switched off in 1977.

InSight mission is not NASA’s first attempt at recording marsquakes. In 1976, the Viking 1 and 2 spacecrafts landed on Mars, each carrying a seismometer. Unfortunately, the seismometer on Viking 1 failed to deploy. The seismometer on Viking 2, which remained on board the lander, failed to detect any marsquakes over the noise of the wind and the lander itself. Viking 2 was a valuable lesson for improving the concept of hunting quakes on Mars. Later still, the Russian Mars 96 mission was set to deliver a seismometer to the red planet. But the mission failed at takeoff.

The InSight lander and its instruments will remain on Mars indefinitely. Usually, a space mission objective is to last at least one Mars year (equivalent to roughly two Earth years). However, most Mars missions have been built to last, and have continued far beyond their primary mission end date. It would be fantastic if InSight followed in these illustrious footsteps, recording marsquakes for years to come.

Space exploration and planetary science are currently undergoing something of a renaissance that is yielding major discoveries. We are exploring the uncharted aspects of other planets, in the same way that historic maritime explorers and geographers mapped our own planet’s hidden secrets.![]()

Katarina Miljkovic, ARC DECRA fellow, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.