Known as Dr. Space Junk, Dr. Alice Gorman is a world-renowned expert on space archaeology. Dr. Gorman takes particular interest in the field of orbital debris and is passionate about the preservation of key objects that orbit our planet for the sake of our cultural heritage in space. In this article, Dr. Gorman highlights why some orbital debris deserves protection and preservation.

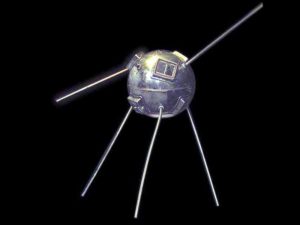

This year is the 60th anniversary of a very special piece of space junk. On March 17, 1958, the US launched a silver sphere of metal the size of a grapefruit into Low Earth Orbit. Vanguard 1 wasn’t the first satellite in orbit, or even the second – but despite coming third, it’s the only one which survives from the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958. The oldest human object in space is still orbiting silently at about 600 km above our heads.

And it’s far from alone. Among the roughly 3000 or so defunct spacecraft which no longer work are many others with their own unique stories. My favourites include Telstar 1, the first active telecommunications satellite launched in 1962, which I’m pretty sure influenced the design of the Doctor Who creatures called the Mechanoids. There’s also the Indonesian telecommunications satellite Palapa A1, launched in 1976, and seen as a symbol of uniting Indonesia’s 17,000 islands and 300 languages. TRAAC, an experimental satellite launched in 1961, carried the first poem into space. Among the stuff we now call space junk are satellites and rocket bodies which reflect visions of space from the Cold War to the cubesat.

But there’s a problem. Satellite technology came to maturity in the 1960s, at the same time as the growth of environmental consciousness. Indeed images of the Earth from space, such as those taken by the first weather satellite TIROS 1, were a big part of this. People were speculating about the impacts of leaving human litter in space from the 1960s, and by the 1990s it was clear that we could no longer ignore the high speed junk that space industry was creating. The risks of a space station or expensive satellite colliding with a bit of space junk and being damaged or even destroyed were just too great.

NASA made the first set of orbital debris mitigation guidelines in 1995, and other organisations followed. The solutions were all passive, designing missions to minimise the amount of new debris created. Actively removing the hazardous objects – ranging in size from fractions of a millimetre to thousands of kilograms – is still beyond our technological capacity. We can try to slow the rate at which space junk increases but we’re not anywhere near reducing the amount.

Because my professional background is working on the heritage components of Environmental Impact Studies on Earth, my first approach to space junk was thinking about how we would do this in space. Was there anything we should keep for future generations? Almost every nation on Earth has some intersection with satellites, even if they are not making or launching them. I started thinking about how to work out what had heritage significance, and what the consequences were for leaving culturally significant space junk in its natural setting.

As it turns out, space industry has already done a lot of the work. We have a catalogue of tracked pieces of space junk, so we know what it is and where it is. Every day, space organisations calculate the likelihood of a functioning spacecraft colliding with a bit of space debris, so we know what the risks are too. Let’s just say we had consensus that a satellite like Vanguard 1 was worth preserving. At the moment, we don’t have to do anything – but if a conjunction analysis showed that it was likely to collide with another spacecraft, then we could reconsider whether it is left in orbit or earmarked for removal – perhaps to a graveyard orbit, or to Earth.

There are other terrestrial heritage processes that work for Earth orbit. I’m not the first person to suggest that it might be a good idea to have some kind of orbital heritage register. Heritage registers are usually established by national heritage legislation, but this won’t work in space. Extending the national legislation could be interpreted as making a territorial claim, against the terms of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. However, an NGO like UNESCO or UNOOSA could be the custodian of an indicative list. It wouldn’t be legally binding, but it would have moral weight. The UN already keeps a register of launched objects so this would be a logical extension. If the heritage list was incorporated into the debris models that are used to calculate collision risks, then it would be possible to monitor the status of heritage-listed debris.

People are sometimes a little horrified that I want to save some space junk, assuming that all space junk is an equal risk to active space missions. Fortunately that’s not the case. On Earth, as a heritage manager, my job is to balance competing claims, for example, between a developer who wants to open a mine, and an Aboriginal group concerned about the places culturally significant to them in the mine footprint, and try and get a good outcome for all stakeholders. There’s no reason why this wouldn’t work perfectly well in space too.

To illustrate this, take the Envisat satellite, launched by ESA in 2002. In 2012, contact with the spacecraft was lost. It’s an orbiting junk time bomb. Firstly, it’s massive, at over 18,000 kg. It’s located in a high density orbit, and every year a couple of other bits of junk pass very close to it – so it’s only a matter of time before a collision occurs. At hypervelocity, this could cause Envisat to break up and dramatically increase the scale of the debris problem. No-one wants that outcome and it’s at the top of everyone’s hit list for removal, when we’re able to do that. Removal will probably mean finding a way to lower its orbit until the atmosphere drags it back in to a fiery death.

Envisat is a pretty interesting spacecraft, and you could argue that it has heritage value. But in this case, the impacts of collision outweigh the heritage significance. It doesn’t mean passively accepting death, however. Envisat might be sacrificed but some resources put towards documenting the technology and history of the satellite – what’s called an offset in environmental management.

It might be time to rethink what we call space junk, however. A widely used definition of space junk is an object in Earth orbit which does not now, or in the foreseeable future, serve a useful purpose. Vanguard 1 doesn’t serve a useful scientific or commercial purpose at the moment – but it does serve a cultural purpose. It’s a material representative of the early space age, demonstrating where contemporary space technology came from. This year people will be celebrating this technology in a way that would be very different if the physical satellite didn’t exist. So I’d argue that Vanguard 1 isn’t junk. Elon Musk’s red sports car, launched into space in February, also demonstrates this. It was never intended to have a scientific purpose: its function was purely symbolic and cultural. It can perform the function of being a fetish or talisman for a whole raft of hopes and desires about space as long as it exists. It will never be only space junk.

Dr. Alice Gorman is an internationally recognised leader in the emerging field of space archaeology. Her research on space exploration has been featured in National Geographic, the Monocle, and Archaeology magazine. She is a faculty member of the International Space University’s Southern Hemisphere Space Program in Adelaide.

She has worked extensively in Indigenous heritage management, providing advice for mining industry, urban development, government departments, local councils and Native Title groups in NSW, WA, SA and Queensland. She is also a specialist in stone tool analysis, and the Aboriginal use of bottle glass after European settlement.

Alice is a member of the Executive Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and a Councillor of the Anthropological Society of South Australia. She tweets as @drspacejunk.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space