Dr. Beth O’Leary is a foremost expert and pioneer of space archaeology and has been involved in the development of the science for the last 20 years. Inspired by a question raised by a grad student, O’Leary has tirelessly worked to promote the protection of humanity’s heritage sites in space. Here, she speaks to Helen Jameson, Editor-in-Chief, SpaceWatch.Global about her inspiration, the progress of the field and the future as humanity plans a return to the Moon.

Can you begin by telling me how you initially found yourself getting involved in space archaeology? What was the attraction?

I always wanted to be an astronaut and I was in high school when they landed on the Moon. I was an exchange student in Bergen, Norway and I remember those grainy images and how exciting it was because everyone around me was speaking Norwegian and at the time I didn’t, and to hear that deep Texas accent say ‘The Eagle has landed’ made me want to be an astronaut.

Unfortunately, there weren’t any female astronauts at that time, and my journey to space archaeology and heritage began because of a very good question from a New Mexico State University Anthropology grad student, Ralph Gibson. He asked me: “does federal preservation law apply on the Moon”. I had been teaching a seminar on the US Federal law and I thought it was a great question. So we decided to find some money so that we could go and do some research and luckily, here at NMSU, they have what is called the New Mexico Space Grant Consortium. That’s an educational outreach programme of NASA that gives funding to researchers working on projects about space. When we proposed this in 2000, it was the first time a humanities scholar had ever asked this question and the director, Pat Hynes, believed in the project. So, myself, two students, and my colleague, Dr. Jon Hunner were awarded the money to research two questions: 1. Does federal preservation law apply on the Moon and 2. What’s up there? We started that journey and we realised that we obviously couldn’t go back to the Moon and because there were so many lunar sites we would have to focus on one site. That was the Apollo 11 Tranquility Base site the first human lunar landing. So the reason why I am here has spiralled from that question.

This is an emerging field in itself but has it become more prominent and is it receiving more attention?

Yes I think so. When you approach people and say space archaeology is the study of the relationships between patterns of material culture and human behaviour that happened in space, people get that. They also get that these artefacts and these sites are important to all of humanity. I have never had someone say to me that this is not a significant area to study. I think consciousness has been raised.

I have noticed recently that the Google XPrize has been discontinued. I find that interesting and challenging because that began that the same year as we did. I assume there are certain groups that will continue to try to get there. What discourages me is that it also shows after so many years, we are still in a very grey legal area about how to preserve and safeguard the cultural resources on the Moon and in outer space. Today, with Neil Armstrong passing away in 2012, 50% of the Apollo astronauts are now gone and people all of sudden say it must be a historic era if the known figures from that event are no longer around. That 50 year rule is both psychological and a part of the U.S. Federal Preservation Law in that sites less than 50 years have to be exceptionally significant to be listed. So, I think that as we approach the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing there will be another spike of interest in what’s on the Moon and how to save it.

We have heard much about the requirement for a legal framework that can be applied to sites on the Moon and Mars and the complexities this throws up. These are different celestial entities. What about the issue of ‘ownership’ of sites on the Moon? Should this be regarded as common heritage for all of humanity? Can you tell us about the legal and policy challenges that are so critical to the future of these sites? How are they being addressed?

I am a firm believer that the lunar sites are the common heritage of humanity. Yes, the US got people there. The former Soviet Union was the first to get to the Moon and has many robotic sites up there and there are many other nations that have cultural artefacts there, too. But it is the common shared knowledge and brilliance of humanity that allowed us to leave the Earth so, in a sense, it is a commons.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, Article 8, says that those nations or states that put artefacts or personnel on the lunar surface retain ownership so in effect, NASA is a Federal Agency of the US and it retains ownership. What seems to need to happen is that an agreement should be put in place around the world that states that these sites are places that everyone has a common interest in preserving – even if the other space treaties state that the US owns the artefacts at these sites. It’s really important that the international community buys into it.

When I started this project, I wrote to NASA and said let’s make the Apollo 11 site a national historic landmark and I knew bad news was coming when I got a letter from their lawyer saying that the US would be perceived as claiming sovereignty over the lunar surface. Here’s the trick. NASA owns the artefacts. They don’t own the surface, or the footprints.

There have been various ideas put forth over the years. UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention is a wonderful way for signatories to say yes, these sites are important and exceptional to all of humanity – Pyramids of Giza, Stonehenge – but it’s never been tried off the Earth. There’s nothing in the convention to say that this applies to space heritage and again, these agreements were written in 1966 and 1972, when the space programme was in full force and no one was thinking about heritage at that time.

There have been various symbolic efforts and two of those came out of California and New Mexico to put the artefacts and structures at the Tranquility base site on the State Registers because the site is relevant to the history of those particular states in terms of space exploration. Again, those are symbolic and neither California nor New Mexico are claiming that site on the Moon. There were two congresswomen from Texas and Maryland that wanted to make a national park on the Moon in 2013, but that was flawed because the Park Service doesn’t have jurisdiction on the Moon. So really when I look at ways in which to go, it’s multilateral or some kind of new treaty that allows those space faring nations to buy in and say, yes, these lunar sites are important.

I wish that the emphasis was on what’s up there because there’s over 200 metric tonnes of cultural material on the Moon, some of which is missing – it’s there but we don’t know where it is. So we have to be cognisant not just of Apollo, but of the earliest Soviet sites which really set the tone for going to the Moon. The Chinese created a site up there and that’s part of cultural heritage. Even recently when the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was launched and part of the rocket crashed into the South Pole, there’s another archaeological site. So I look at the Moon as a place that we have an abundance of opportunity to see what’s there. We have amazing documentation though you would be surprised what’s fallen through the cracks when engineers took drawings home for example, but we have an absolutely extraordinary amount of visual documentation of what’s on the Moon and so we need to manage all of this as a cultural resource.

What are your thoughts on the private missions such as PTScientists going back to the Moon? How excited are you about this prospect? What are you hoping they will be able to discover and what does this mean to your scientific community?

The NASA guidelines of 2011 were something that I helped work on with one other humanity scholar, Roger Launius, who at the time was at Smithsonian. The rest of the group were NASA scientists. Those guidelines, which don’t carry legal force, single out the Apollo 11 and 17 sites as they were first and last and are two of the most interesting places that people have visited, and need protection. I think that it’s important that whoever decides to go, respects those guidelines. https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/library/reports/lunar-artifacts.html

Archaeology sometimes works the best when people don’t go back. When they avoid impacting places that they know are significant until they really have a very robust and good data recovery plan so that the questions that are asked can be answered by a visit to the site and that most of the site is still preserved. Archaeology really is scientifically organised and documented destruction of what people did in the past, so as archaeologists we say avoid this place and go around it. Don’t touch it until there really has to be an impact and until we are aware of what the important questions are to ask at the site and how can we best answer those questions while destroying some of the qualities that make that cultural heritage important. We gain the information by scientific recording and documentation. I always approach archaeological data recovery with trepidation; I do this on Earth too. Why do we want to go back and what are we going to learn?

Looking at the effects of the lunar environment on these sites is really important. Archaeologists look at site formation processes all the time. How did micro meteorite impacts affect the material there such as rovers and footprints, etc? How do we understand how a site changes through time? It’s like taking a life history of a site. And again, archaeologists would love to see a total picture and look at all the Apollo sites as a total sum and everything that’s there and ask what do we sample? Where do we choose? How do we go back and approach these sites to answer some very interesting archaeological and scientific questions? When I was working on the NASA guidelines there was a guy there who was a geologist and he said if only Harrison Schmidt had collected a few more samples in the Taurus-Littrow valley. There are so many more questions. There is more science to be done as well as trying to preserve those values that make it part of our space heritage.

How far do you think we are in terms of getting to a point of agreement? As you say, it will be multilateral. How far away are we form something that is workable?

I don’t know. I am not a legal scholar or a lawyer. My understanding is that things that happen at an international level are glacial. They proceed slowly but at the same time, UNESCO has a marine archaeology act for looking at cultural resources underneath the ocean, which is a remote place that happens to be on Earth. Then there’s Antarctica, which again is a commons, and has designated certain ‘explorer’s areas’ as important. Interestingly enough, Antarctica is visited by something like 40,000 tourists a year who have picked up souvenirs and walked away or damaged things. So those treaty countries in Antarctica have got together to agree on how to manage these cultural resources. I think the time is right. I’ve waited 18 years and that’s a long time but maybe in the next ten it will accelerate and people will see that we need to have agreements about cultural resources on the Moon. There are groups like For All Moonkind working towards this goal.

If you think about all the work that ESA is putting into the Moon Village and how we are actively talking about building Moon bases, asteroid mining and using the Moon as a springboard to other planets so surely something will emerge soon?

One can only hope and as we develop space, people will go back to the Moon, I’m convinced of it. We have a chance to step back and breathe and say ok, how can we plan for this? We know what’s worked on earth, although imperfectly. We have ways of evaluating sites, we have the World Heritage Convention, we have the Burra Charter in Australia, the National Register of Historic Places in the US. We have some mechanisms and frameworks that we know are feasible, but the challenge is how we get people to agree on preservation.

Obviously, there are multiple needs and multiple ways that people need to interact but cultural resources have been on the back burner. It’s a ‘been there, done that’ attitude. I think that, unless there is a commitment made by many nations to say I agree that my artefacts AND your artefacts are important and your sites are important as well, that’s when change really happens and takes incredible effort and leadership to get that. But it’s necessary. People ask me, what’s the threat now? I don’t know. Google just cancelled their XPrize. Does that mean that’s it? No one will go back? I don’t think so. We’ll be going back to the Moon.

A lot of the planning in missions for different satellites etc, is end of mission agreements. They say, at the end of the mission, certain things must happen for safety reasons, and so that the information is preserved. Not necessarily the artefact, but the information. To me and my colleagues, Low Earth Orbit has a lot of cultural debris.

I’d like to ask you about orbital debris. Whilst the space industry is engaged in discussions about how we limit it and even remove it, some objects are of huge significance to the space archaeology community. Where do you start in terms of identifying what is worth preserving and how do you go about ensuring that it is respected?

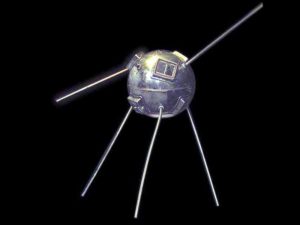

What bigger challenge is there than the challenge of orbital debris? There’s a lot of junk but there are important things up there too. It’s important to preserve what’s up there. I think JFCC tracks over 23,000 items of debris greater than 10cm and god knows how much up there is smaller than that. Some of the big things that I see that as important are the earlier space age satellites such as Vanguard which was launched in 1958. One of the things about preservation, and this is a slightly tricky concept, is that Vanguard is being preserved in fairly stable orbit and NASA believes it will be there for another 600 years. So to all intents and purposes, it’s in a kind of in a museum though it will eventually de-orbit. Telstar 1, which was the first active telecommunications satellite and the Syncom 3 satellite which was one of the first geostationary satellites are all still up there, so all of these are from an age when we were first figuring out how to get into space and how we use space. Those cultural resources are very important.

When you get into cubesats and small satellites, that’s a different matter and it raises the matter of safety. Some of the terrible crashes that have happened in orbit have occurred when some defunct satellite has come out of nowhere. Even personnel on the ISS has been prepared to be evacuated because of potential crashes with other orbital debris. Do I think that we need to capture Vanguard and bring it back and put it in a museum? No I don’t think so, but the fact is that we can pretty effectively track its orbit and as such, it is being preserved. Look at Mir. That was de-orbited. That was the first international space station held together with duck tape and wire and we’ve lost it. The cost to boost it to a Lagrange point and out it out of harm’s way was not considered and perhaps could not be at the time. I guess a lot of it is burned up and is in the Pacific Ocean near Australia, so we now have to think about the future for the Hubble, and the ISS. The ISS is a whole archaeological site in itself. Some of my colleagues are looking at that aspect.

Finally, what are your personal hopes and dreams as a space archaeologist? What would you like to see happen in the future and how would you ideally like to see the science evolve?

Well I hope that it will continue and there will be a new generation of archaeologists that will carry the ideas forward. One of the things in my archaeological career, and I started in 1970, is that I have watched technology revolutionise my field. We used to go out with compasses and triangulate but now you have GPS. For example, if only they had better resolution on the LRO mission, some of those archaeological sites would have been so much clearer. Using the remote sensing tools that we have to provide data will encourage archaeologists to look at these patterns of material culture, to study the relationships and find out what we can learn about human behaviour. We are not historians or physical scientists, we have a unique perspective so I am hoping that an archaeologist gets on the next team to the Moon. We had a geologist up there, but if an archaeologist could be a working member of the investigating team, that would be wonderful wherever we go – whether it’s back to Moon or Mars.

Professor Emerita, Department of Anthropology, New Mexico State University Ph.D., M.A. Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, B.A., Anthropology, Mount Holyoke College,

Dr. O’Leary had a teaching career at New Mexico State University in Anthropology. From 2003 to 2011, she was appointed by the Governor to the New Mexico Cultural Properties Review Committee. She served as an expert witness in federal court in multiple Archaeological Resources Protection Act cases and has broad experience in archaeology and cultural anthropology, concentrated in New Mexico, Texas, and Yukon, Canada.

For the last 18 years Dr. O’Leary has been involved with the cultural heritage of outer space and the Moon and is one of the creators of the field of Space Archaeology and Heritage. With a grant from the New Mexico Space Grant Consortium (NASA), she investigated the archaeological assemblage and the international heritage status of the Apollo 11 Tranquility Base site on the Moon. In 2010, she and colleagues successfully nominated objects and structures at the Tranquility Base site to the State Registers of Cultural Properties in both California and New Mexico. She was invited by NASA to work with a team of scientists to produce “NASA’s Recommendations to Space-Faring Entities: How to Protect and Preserve the Historic and Scientific Value of U.S. Government Lunar Artifacts” (2011). In 2012, she received an award from NASA for that work.

Dr. O’Leary has chaired five international symposia on Space Archaeology and Heritage. She is a member of the World Archaeological Congress Space Heritage Task Force. Her books include: (2017) The Final Mission: Preserving NASA’s Apollo Sites, (with co-authors L.Westwood and M.W. Donaldson, University Press of Florida.); (2015) The Archaeology and Heritage of the Human Movement into Space (with co-editor, P.J. Capelotti, Springer International Press); and

(2009) The Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology and Heritage (with co-editor A. Darrin, CRC Taylor and Francis Press).

A pioneer in this evolving field,she has been interviewed by national and international media, including among others: Smithsonian, National Geographic, New York Times, LA Times, NPR, Deutsche Radio, Sunlife (China), USA Today, Geo, Scientific American, Ars Techica, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She has written articles for BBC, Antiquity, and the Washington Post.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space