by Luisa Low

During this week’s Space Café, SpaceWatch.Global publisher Torsten Kriening sat down with Professor of Science and Technology Policy at the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, Japan, Kazuto Suzuki.

Having received his PhD at the University of Sussex, Professor Suzuki has worked internationally as a strategic policy analyst and advisor in space and military space policy, with research positions at the University of Tsukuba and the Fondation pour la Recherche Strategique in Paris.

He has also served as an expert in the Panel of Experts for the Iranian Sanction Committee under the United Nations Security Council and contributed to the drafting of the Basic Space Law of Japan.

He now serves as a member of Sub-committees of industrial policy and space security policy of the National Space Policy Commission.

This week, he and Torsten discuss his home country’s place in the space race, and how as a late-starter like Germany, Japan has become a leading, spacefaring launch country whose ambitious plans for debris removal could change the fate of space for good.

Japan, space and their military: where they started

As you might expect from a modern, industrial, advanced manufacturing powerhouse, Japan – the world’s third-largest economy – is powering ahead with numerous space initiatives and policies.

But the country’s early forays into space weren’t so fruitful. In the years proceeding World War 2, like Germany, Japan’s access to early space technology was limited due to its dual-use nature. To make amends for World War 2, Japan also imposed self-restrictions, making the commitment to not develop offensive warfare such as missiles and defence carriers.

Japanese National Diet – Japan’s bicameral parliamentary system, which consists of a lower and upper house – unanimously decided that Japan should exclusively use space for peaceful purposes. This began to change in 1985, when it allowed the military access to commercially available space services.

But, when everyone else is doing it, is total abstention from martial space possible?

In response to the increased militarisation of space and tensions with China and North Korea increasing, in 2008 The Japanese National Diet introduced the “Basic Space Law”, which has allowed the military to use reconnaissance and communication satellites with their ally, the United States.

“Ever since then, Japan has invested in space – mostly in space situational awareness. We are building [these] capabilities under the Ministry of Defence, but there is only one dedicated satellite for the military, but the military doesn’t own or operate the reconnaissance satellite or any space assets, other than communication satellites. So, that is how it is in Japan.”

Where they’re going

Yesterday, G7 nations committed to the safe and sustainable use of space.

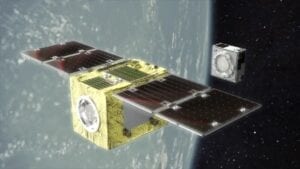

A central facet of space sustainability is the management and removal of space debris, using active debris removal (ADR). This is an area Japan is leading in, with Tokyo-based company AstroScale, through their Oxfordshire subsidiary, developing a technical demonstration of space debris removal.

But how is space debris removal profitable when space operators have skirted around the issue for so long? The way around it, Professor Suzuki says, is to hold nations and operators to account on an international stage, which would then encourage them use outfits like AstroScale, to clean up after them.

“But in the future, I think there’ll be a sort of an establishment of the understanding of what is responsible behaviour in space – this has been now led by the UK and adopted last year in the United Nations General Assembly.

“And I think this is the sort of a step forward for making this debris removal as the actual business case.”

Is ADR the dual-use “slippery slope”?

If ADR can take out debris from a satellite, can it also take out a satellite? And could this create a legislative conflict for Japan, whose military is legally bound by the Japanese National Diet to refrain from martial space activity?

Professor Suzuki believes AstroScale’s very advantage is operating as a commercial entity, rather than a government because it means they will be driven by corporate gains, rather than any political regime.

“If, for example, this technology was being developed by a big country, like, the United States military or the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, then people would immediately find a certain intent in developing such technology.”

“If AstroScale is doing something which is unusual and not authorized, and takes out debris or any satellite, that will be the end of the business.”

“So actually, in a way, that a private company is engaged in active debris removal is much better than if a national government was involved.”

“Because these activities are controlled and licensed by the Japanese government, [there is a] very strong focus on the transparency on this matter. Transparency, I think, is the key: you need to show what your intent is.”

Japan – space’s Northern Star?

With thousands of satellites being launched by private companies each year, the issue of space debris is gaining momentum with over 100 million shards rocketing around earth’s orbit.

Although there is progress on the issue, such as the UK’s initiative for responsible behaviour in space, Professor Suzuki says there have been few opportunities for international consensus, meaning real action on the issue is lagging.

Because of this, he believes countries like Japan must take action, by developing an urgent protocol for the management and removal of space debris, lest the problem spins out of control.

“I think this sort of precedent needs to be set. Japan will unilaterally approach to set the precedent, and set an example. Whether other countries follow or not – it’s up to other countries – but at least, it’s a starting point. We need to take an action, we need to do something in order to start turning things around.”

To listen to Professor Kazuto Suzuki’s insights into diversity in space, you can watch the full program here:

Space Cafe is broadcast live each Tuesday at 4 pm CEST. To subscribe and get the latest on the space industry from world-leading experts visit – click here.

Luisa Low is a freelance journalist and media adviser from Sydney, Australia. She currently manages Media and Public Relations for the University of Sydney’s Faculty of Engineering.