by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 9 – 15 August 2021”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 9 – 15 August 2021”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup! A special shout-out to our friends at GoTaikonauts!, and at SpaceWatch.Global, both excellent sources of space industry news. In particular, we suggest checking out GoTaikonauts! long-form China reporting, as well as the Space Cafe series from SpaceWatch.Global. Without further ado, the news update from the week of 9-15 August 2021.

1) Space Transportation Completes RMB300M Series A round of funding, gives more insights on hypersonic vehicle roadmap

Jean’s Take

Chinese hypersonic spacecraft and rocket company Space Transportation announced an 300M RMB Series A funding round on August 9th. Before I let Blaine get into the identity of the investors involved in this new round of funding, I want to discuss a little bit the very nature of Space Transportation’s range of products, which seems to have evolved quite a bit with this announcement.

Space Transportation is a Beijing-based company founded in August 2018, and was known up to now as an aspiring suborbital and orbital rocket manufacturer, one among the 15-20+ commercial launch companies that have surfaced over the past 7 years.

It is not necessarily the most well-funded, the most advanced, or generally the most high-profile company, but it stood out regarding its reusable rocket technology choices: exploiting lift generated by a lifting surface. This was in absolute contradiction with the general consensus in the Chinese commercial launch sector that reusability would be achieved by a SpaceX Falcon 9-style retropropulsive landing.

The CEO is Wang Yudong, a Tsinghua University graduate who has a long experience at CALT including positions as a chief designer and director.

As spaceplane activities on both sides of the Pacific increasingly attracted attention due to the potential dual-use of such technologies, Space Transportation came into the spotlight as it performed a number of suborbital tests with clear lifting surfaces visible on pictures. This notably consisted into two suborbital launches of the Tianxing-1 rocket:

- In April 2019, the first test flight of the Tianxing-1 rocket (in collab. with Xiamen Uni)

- Again in December 2019, a second Tianxing-1 test flight

Let’s take a closer look at Space Transportation’s aspiring-family of products, the Tianxing rockets, which have changed quite a bit over time.

We know that Space Transportation is or has been at some point keen on 4 types of products:

- Suborbital hypersonic test vehicles

- orbital launch vehicles (putting a payload into orbit)

- Point-to-point space transportation

- Suborbital space tourism.

Let’s break these down and see which ones Space Transportation will actually develop in the future.

- Suborbital, hypersonic test vehicles

This type of product will 100% be in Space Transportation’s product portfolio because it already is: the Tianxing-1 is exactly that. The idea is to have a suborbital spacecraft speed up sufficiently to high Mach regimes (>Mach 5) to enable various customers to test their systems at hypersonic speeds.

This may seem like an expensive way to test things, and indeed aerodynamicists tend to prefer to use wind tunnel testing for experiments whenever possible. The issue is high mach number wind tunnels are very hard to manufacture, and expensive. Beyond a certain Mach regime it becomes necessary to use another technique (for reasons linked to the physics of fluids that won’t be discussed here), called the expansion tunnel, which can reach very high Mach numbers but only for a very short time.

For these extreme conditions, it becomes possible that actual tests (such as on-board the Tianxing-1 rocket) become more attractive, in terms of complexity, realism, and maybe even in price, as the Tianxing-1 is reusable, performing horizontal landing like an airplane thanks to the delta-shaped wings on each side.

The Tianxing-2, currently under development, will also be a hypersonic test vehicle, able to reach Mach 10. - Orbital Launch Vehicles

Orbital launch vehicles refer to rockets that are able to carry a payload (such as a satellite) and put it into orbit, with significant deltaV for the latter to stay in space. Basically, the launch vehicles that we are familiar with.

This would potentially be the Tianxing-3, and we’ve seen mock-ups on previous Space Transportation marketing material showing a two-stage rocket: a first stage spaceplane which would carry what looks like a solid-fueled second stage. The first stage would be able to glide back and land on Earth, leveraging reusability to lower costs.

Unfortunately for spaceplane fans, in the diagram shown in this week’s round of funding announcement, the orbital spaceplane configuration is no longer apparent. - Point-to-point space transportation

Point-to-point space transportation is another one, with the idea of sending people or cargo across the globe in a rocket, which could cut down long-distance travel by a factor of 10-15x. Most people are probably familiar with this idea coming from SpaceX’s ambition to do this with Starship, and with a fancy video published in 2017 of what this would look like.

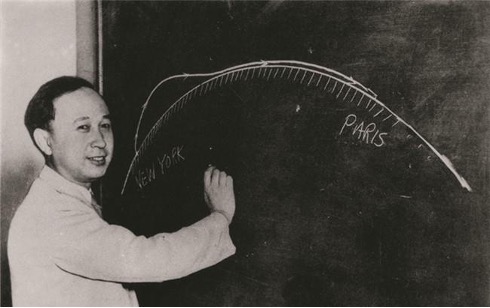

The idea of point to point space travel is actually much older than that, and can be traced back all the way back to the 1940s and to the works of engineers like Eugen Sänger. We can also mention Qian Xuesen, the father of Chinese space, who at the time was working at Caltech in the US.

We don’t have much information on what Space Transportation’s point-to-point transportation space vehicle would look like, but they do show such a vehicle in their most recent funding round announcement, and this is something that their CEO Wang Yudong has discussed at length, notably in a keynote presentation as early as 2019.

- Space Tourism

Last but not least, and definitely a very topical subject in 2021, is space tourism. This has been a constant in Space Transportation’s plans, with various mock-ups showing up in their presentations over the past years.

Early presentation of the Tianxing rocket family

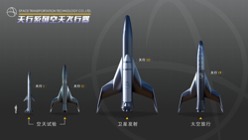

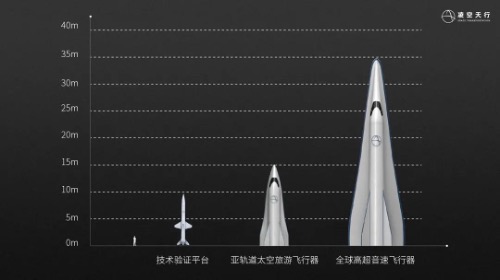

Space Transportation rocket family shown in this week’s announcement

How likely is any of this to materialize? If I was to do a little bit of speculation here: I would say the suborbital hypersonic test vehicles for sure (composed of the already operational Tianxing-1 rocket and the Tianxing-2, under development). Orbital launch vehicles also seem quite probable, if a second stage to the current Tianxing rockets was to be developed, although this type of product is not mentioned in the recent funding round announcement.

However I am not sold on point-to-point space transportation, due to safety issues and the very sophisticated propulsion technology that needs to be developed. But then, Wang Yudong does seem strongly driven by this activity if you watch his keynote from 2019.

As for space tourism… I don’t know. It may seem a bit less demanding from a technology point of view compared to point-to-point travel, but there’s the question of: is there an actual market for this activity in China? Especially in a society that could be perceived as a bit more risk-averse and with a current political environment where the rich tend to lay low.

Let’s remind ourselves that Space Transportation is still a very young company (founded in 2018!), and we’ll have to wait and see which path it will take, but I have a feeling that when you are a commercial company, sooner or later it’s the market that will drive your business decisions.

Blaine, any speculation for your side on which activities will actually materialize?

Blaine’s Take

You covered it well, and I learned a new word: aerodynamicists. And indeed, what a very appropriate (though perhaps not so creative) name for a space transportation company, Space Transportation.

That said, some points to add from my side on the commercial/financing side of things. First, interesting to note that in a 2019 interview, Wang Yudong mentioned that the cost for the Tianxing-1 would be not more than 5 million RMB, which is to say, like US$800K. Not cheap, but also probably a lot cheaper than building an expansion tunnel, and indeed, probably cheaper than a 2-bedroom apartment in urban Beijing or Shanghai. In the same interview, Wang noted that the Tianxing-1 could be reused at least 3 to 4 times, and that the cost for a Tianxing-1 can be recovered after only 2 launches, indicating an apparent manufacturing cost of <10 million RMB, or two Shanghai apartments. There is apparently demand for the services, with the company having announced in 2019 that there were 4 customers onboard the two test flights it had completed at that time.

A couple of other small points on Space Transportation before we dive into funding. An excellent article from 2019 describes CEO Wang’s starting the company. Apparently he left his previous job at CALT, and claims to have designed the Tianxing-1 on paper in about 2 months (though frankly, due to the enormous complexities involved with developing such a rocket, it’s unlikely that any one person could design a hypersonic rocket like this to any significant degree of completion in a 2-month span). Soon after, he met Li Liang, a former CASC engineer, who told him that he could turn the paper Tianxing into reality in….three months. Again, tough sell, but it makes a good story, and I have no proof of otherwise.

Li noted that in traditional space companies, the same task was measured in years. Li also noted that in the traditional space program, certain sensors had fixed suppliers and the parts cost in the range of 20,000 RMB, whereas you could buy comparable sensors on Taobao for a few dozen RMB. Slightly better deal, and a great example of the scrappiness and resourcefulness of Chinese commercial space (also the magic of Taobao). It’s also perhaps no wonder that a flight on the Tianxing-1 can be procured for the low, low cost of 1 urban Shanghai apartment.

Back to the current funding round–this funding round was led by Matrix Partners China and Shanghai Guosheng Investment Fund. In a related press release, lead investor Matrix Partners noted that “The product of Space Transportation is high-speed aircraft. Imagine flying from the Eastern to the Western Hemisphere in less than 2 hours. This may be the next generation of aircraft”. As Jean mentioned earlier, this may or may not be realistic, but overall a very bold statement.

In the announcement for this round of funding, Space Transportation noted that they plan to conduct technology verification testing until 2022, achieve a suborbital space tourism prototype flight in 2023, and conduct the first manned test flight of a suborbital space tourism vehicle in 2025. They plan for their first “global hypersonic vehicle flight” in 2028, and then the first “full-scale global hypersonic vehicle flight” in 2030.

Overall, a big update from Space Transportation, and for China’s hypersonic spaceplane sector more generally. The company has moved remarkably quickly thus far, and appears to have pulled together a great founding team with a lot of entrepreneurial drive and street smarts to round things out. Very much looking forward to seeing what comes from Space Transportation in the coming years.

2) Further hints that China is working on a lunar lander

Jean’s Take

A Chinese local space media Dianfeng Gaodi pointed out something interesting over the past week, the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics of Xiamen University published a highly interesting WeChat post on July 5th that almost went unnoticed, and that covers the visit of some high-level officials from CAST to the university. So what’s so unusual about that?

While in appearance quite unremarkable, the post actually nominatively refers to the visitors as high-profile Chinese lunar lander project leadership, namely:

- Yang Lei – chief commander of the crewed lunar spacecraft (载人登月飞行器系统总指挥)

- Li Yan – deputy chief commander of the lander module of the crewed lunar spacecraft (载人登月飞行器系统着陆器副总指挥)

- Fan Songtao – deputy chief designer of China’s next generation crewed vehicle (新一代载人飞船副总师)

This story is of interest because the lander is one of the missing pieces of China’s crewed lunar projects. That’s because so far, most of our knowledge on China’s lunar program covers:

- The overall roadmap, which was unveiled this year and called the ILRS, with 3 distinctive phases (Reconnaissance, Construction, Utilization), spread over 15 years (2021-2036+). We also know that potentially China could also attempt crewed lunar missions outside of the context of the ILRS.

- The lunar rockets: notably the Long March 5DY and the superheavy Long March 9, which will likely both be human-rated and be able to launch taikonauts to the lunar orbit

- A deep space capable crewed capsule: so far called the Next Generation Crewed Vehicle (新一代载人飞船). The NGCV will be capable of carrying a crew of up to 6-7 taikonauts. A small-scale prototype and full scale prototype were launched respectively in 2016 and 2020.

We are still missing tangible information on the remaining essential piece: the lander and ascent vehicle, which will bring taikonauts down to the lunar surface and back up to lunar orbit. It is publicly known information that China is working on the lander: on April 23 2018, Zhou Jianping announced a competition requesting proposals for a lunar lander architecture (full detail on lander characteristics available on CMSEO’s website). And also, at the China Space Conference in September 2020, some detail was shown on a lunar lander proposal, as can be seen on the screenshot. There was even some mention of a lunar surface vehicle and lunar space suits.

So far, China’s first crewed lunar mission could look somewhat like this: using the Long March 5DY lunar launch vehicle (see Dongfang Hour episode 39 for more info on the launch vehicles), 2 separate launches would put the NGCV and the lunar lander module into translunar injection, and which would then dock together once in lunar orbit. At some point, the new NGCV-lander assembly would lower its orbit, and the lander/ascent vehicle would then undock, perform an autonomous landing, and once the lunar mission is complete, the ascent vehicle would bring the taikonauts back to lunar orbit to dock with the NGCV.

So while the lunar lander is not yet official, it’s undoubtedly there and under development, meaning that it could be potentially revealed in the near future (maybe China Space Day 2022? 100% speculation).

Blaine’s Take

We should make a betting pool on which city will host the 2022 China Space Day. If I were to bet, I would say Tianjin or Guangzhou. Also jealous of the CAST crew to have been able to make the trip to Xiamen, I can only hope they took the time to visit Gulangyu, and ideally had some 沙茶面. Last admin point, check out DFHour episode 39 for more info on the LM-5DY.

Only a couple of very small points from my side: first, interesting to note that the Chinese lunar plans, at least to now, seem to be aiming for a mission directly to the lunar surface, as opposed to the Artemis Program’s Gateway Lunar Space Station. That said, we did see a presentation from the 2020 China Space Conference in Fuzhou (not the one in Jiangxi) that noted “Lunar Orbital Space Station?”, as though to say that China is considering an orbital station, but has not yet confirmed. Second, this is but the latest instance of Xiamen University popping up in the space sector. The university has been active in recent months, with the Haisi-1 and Haisi-2 SAR EO satellites having been launched in December 2020 and June 2021, respectively. The two EO satellites appear to be part of a bigger constellation which has a maritime silk road component to it (Haisi would refer to maritime silk road, i.e. 海丝 being short for 21世纪海上丝绸之路/Shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lù). Finally, Xiamen University was also involved in the aforementioned April 2019 test flight of the Tianxing-1 with Space Transportation. Interesting stuff, and big thanks to Dianfeng Gaodi for pointing this out (excellent account btw).

Moving into our last major piece of news for episode 1, we have a couple of updates from in-flight connectivity and

3) China Eastern Begins Live TV In-Flight w/ Panasonic

Blaine’s Take

China Eastern Airlines will begin rolling out live TV on its widebody fleet of A330s, A350s, 777s, and 787s, including content from CCTV and CGTN, through IFC service provider Panasonic Avionics. The addition of live broadcast on flights is made possible partly by the bringing into service of Apstar-6D, a Ku-band HTS with considerably more capacity than any other Chinese-owned satellite in orbit today (~50 Gbps).

In related news, we also saw Panasonic Avionics launch what the company calls the “world’s first full cabin 4K in-flight entertainment system”, with Cathay Pacific on the airline’s A321neo fleet. Interestingly, the technology will also be bluetooth-enabled, which means that passengers can watch 4K content using their own bluetooth-enabled headsets (surely a win for sanitation in this age of Covid-19). The Cathay offering will involve an 11.6-inch personal screen in economy, with a 15.6-inch personal screen in business class. Notably, Cathay Pacific is arguably the hardest-hit airline in the world during the Covid-19 pandemic, with Hong Kong having zero domestic flights, and with international travel down literally 99% from pre-Covid levels. Whether 4K flights with bluetooth-enabled sound will help the airline rebound is anyone’s guess, but probably they would need the Hong Kong government to open the borders first.

Overall, a couple of interesting developments, moreso the China Eastern one in that IFC and IFE in China tend to be less straightforward from a regulatory perspective than Hong Kong. IFC in China remains badly underdeveloped, with aircraft penetration rates of ~5%. This is due to several factors: regulatory roadblocks, insufficient satellite capacity to make a decent business case, and very conservative state-owned airlines. I recall an interview with Air China Executive Chi Zhihang at Euroconsult World Satellite Business Week in 2019 where he said they are considering IFC for their North America routes….in five years.

That being said, these factors are starting to change. Regulations have become much clearer around IFC, and new capacity has entered the market in the form of Apstar-6D. Moving forward, state-owned satellite operator China Satcom has plans for 3x HTS across Eurasia + Pacific, all of which have a significant IFC component. At the same time, we have domestic equipment manufacturers and integrators starting to advance their technology to the point of being able to serve airlines, an important factor in a country that is emphasizing self-sufficiency. All this is to say, moving forward, we should probably expect more Chinese airlines to announce plans for IFC and IFE.

4) Conclusion on SAR story in Youtube comment

Jean’s Take

Also, a special thanks to the author of one of the comments on our past episode discussing competition among Chinese commercial SAR projects. Wb Young discusses how back in the 1980s, his university professor began working on one of China’s earliest SAR designs as a side project. His work gained the attention of the government and obtained several thousands of USD of subsidies to develop a technology verification demonstrator. The university in question was East China University of Science and Technology, and in the end the project included a collaboration with the “14th Institute” for their radar, and the demonstrator was attached and tested beneath the wing of a Ilyushin 14 aircraft.

Unfortunately we don’t have any photos, but it’s absolutely great to have such insights on early Chinese space/aerospace technology, this is something you seldom find on the internet or even in history books. Wb Young, thanks for sharing, 非常感谢!

Blaine’s Take

I can only imagine how far several thousand USD of subsidies would get you in China back in the 1980s. That being said, this is the end of episode 1 of the Dongfang Hour Space News Roundup for the week of 9-15 August. Stick around for episode 2 for China’s New Shepard, among other things. I’m Blaine Curcio, joined as always by my co-host, Jean Deville, and we will see you on the next episode.

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space