by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 15 – 21 Feb 2021”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 15 – 21 Feb 2021”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup! A special shout-out to our friends at GoTaikonauts!, and at SpaceWatch.Global, both excellent sources of space industry news. In particular, we suggest checking out GoTaikonauts! long-form China reporting, as well as the Space Cafe series from SpaceWatch.Global. Without further ado, the news update from the week of 15 – 21 February.

Russia and China close to signing an MoU on Lunar Exploration (according to SpaceNews/Andrew Jones)

Jean’s Take

According to Andrew Jones of Space News, Russia and China are close to signing an MoU on the “International Lunar Research Station” project (ILRS), a concept revealed by China in 2016.

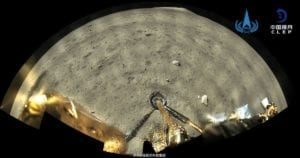

China has a very strong lunar exploration program known as the China Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP). The program was initiated by the orbiter Chang’e 1 in 2007, followed by Chang’e-2 (another orbiter), two lander/rover missions (Chang’e 3 and 4), and a sample/retrieve mission (Chang’e) 5 completed at the beginning of this year. CLEP also plans a second sample return mission in 2023 with Chang’e 6; little is known of the Chang’e 7 and 8 missions, which will focus on critical technologies such as ISRU.

For follow-up missions that would put us well into 2030, China has mentioned long-term robotic missions, as well as possibly crewed missions to the southern pole (which contains ice in permanently shadowed craters). It has been developing a super-heavy launch vehicle the Long March 9, which is planned for maiden flight in the early 2030s. It has also tested in 2020 its next-generation crewed spacecraft.

Foreign cooperation to now has been limited, with China often preferring to conduct missions on its own, but more recently there has been increasing eagerness to let international partners play a larger role in Chinese-led missions, with the most apparent examples being Chang’e-4/6 and the ILRS. While it is unclear what exactly the ILRS would consist of, it has been described as a “first sharing platform in the lunar south pole, supporting long-term, large-scale scientific exploration, technical experiments and development and utilization of lunar resources”. This echoes a bit of ESA’s Moon Village concept and has been met with interest by both Russia and Europe. Worth noting, on Chinese illustrations of the ILRS, a Russian Luna spacecraft is visible.

The ILRS could become a competing concept to the US-initiated Artemis accords, which aims to settle some basis in codifying space law and behaviour in space. While not binding, it sets a precedent as a multilateral agreement made outside of COPUOS (UN), and is controversial as well regarding certain points on “safety zones” and space mining. The absence of Russia and China from the accords could mean that the ILRS could bring different standards to space exploration.

Blaine’s Take

The MoU between China and Russia is not a surprising development, as the two countries have an alignment of interests on many things related to space. That said, I would point out that an MoU is not necessarily a binding agreement, it is simply a Memorandum of Understanding.

That said, China and Russia have had a collaboration in space for some time, for several reasons. First, Russia has historically bought the majority of its space imports from Europe or the United States, implicitly being priced in Euros or dollars. Russia’s economy, and in particular its currency, are strongly linked to the price of oil, which has meant a difficult past decade for the Russian government budget more generally.

The Russian space sector historically has seen problems in good times and in bad times, for example, during times of low oil prices, government budgets are constrained and spending on space projects gets cut. During times of high oil prices, executives at SOEs will pocket a bit of money for themselves, because they know that they need to have some money prepared for the bad times, and the good times might not last forever. As a result, Russia has been trying to 1) import fewer space products, and produce more domestically, and 2) when not possible to produce domestically, start to import from a broader variety of countries, and particularly countries that are willing to be flexible on financing (i.e. China).

Cooperation between Russia and China in space could potentially be highly synergistic. China would presumably be bringing bigger amounts of money, and Russia would be presumably be bringing specific technologies and “knowhow”. The two countries also have some degree of convergence on their views of the world, technology, and information flow, and Russia has bought a lot of Chinese equipment for its own telecommunications infrastructure. The two countries both have vague plans for things like an integrated telecoms, navigation, and EO constellation (Russia calls it “Sfera”, China calls it 通导遥一体化), and it’s conceivable that they would cooperate on those as well.

Bringing it back to the story, I am interested to see how the cooperation between China and Russia develops, both in general and specifically in the context of lunar exploration.

Release of a new report on the Chinese space sector

Blaine’s Take

Earlier this week, we saw the release of a new report from the Secure World Foundation and the Caelus Foundation, “Lost Without Translation”. The report was built on research efforts by the SWF and Caelus to understand perceptions of the US/China relationship, specifically in the context of commercial space.

Primarily reporting from a US perspective, the report brings up some important findings. Some takeaways include:

- Information asymmetry. There is a lot more information available for Chinese actors about the activities of their US counterparts than vice versa. Put another way, today, the US space industry is largely in the dark about China’s activities, and they seem to acknowledge this.

- Desire by US companies and other actors to engage with their Chinese counterparts, but to do so in ways that are well-defined, in areas that allow for protection of IP, settlement of conflicts in neutral areas, and generally a “rule-based” system for space transactions.

- Many American respondents (nearly half) were “not sure” about the question of whether there are Chinese commercial space companies, with roughly ¼ each answering definitively yes or no.

Jean’s Take

I haven’t read the report extensively, but based on your takeaways I can say that the trend is very similar in Europe, from my experience with discussing with European (and notably French) space companies. And perhaps a slightly stronger willingness to develop the Chinese market, to avoid “putting all the eggs in the same basket” (US market). For Europeans however, there is always the question of to which extent working with one market could exclude the company from working with the other.

On another note, with the “Lost Without Translation” report, it’s fascinating to see a 3rd report on Chinese/Asian space being published in the space of 6 weeks, the other two being the ESPI NewSpace in Asia report published early in February (in which Dongfang Hour was a contributor to the CN part), and China’s Ambitions in Space: The Sky’s the Limit, by Marc Julienne, the head of China research at IFRI. The multitude of reports is but one indicator of the dynamism of China’s space sector, with another such example being the developments by major companies related to space…such as Geely.

The announcement by Geely about their satellite factory getting the “green light”

Blaine’s Take

On Thursday 18 February, Geely announced that it had been granted a license to begin commercial satellite manufacturing at its factory in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province. To review: Geely is one of China’s leading automakers, and likely its most famous fully private one. The company owns several overseas car manufacturers including Lotus, Volvo, and stakes in Proton (49%) and Daimler (<10%). The company’s CEO, Li Shufu, is one of several figures that somewhat resembles a “Chinese Elon Musk”. Li is worth around US$22B, a figure that has ~doubled in the past 12 months on the share performance of Geely.

Almost exactly 1 year ago, Geely announced its plans for a constellation of enhanced navigation satellites, as part of Li’s larger vision to transform Geely from an auto manufacturer into an autonomous mobility service provider. At the time, the company announced RMB 2 billion (US$325M) to be invested into the factory in Taizhou, with plans for manufacturing thousands of satellites for Geely’s planned constellation. This is clearly a major project and one that leads to several important questions in the Chinese context:

- Will Geely be able to compete with Hongyan/Hongyun/other state-owned constellation? Probably not, but, it probably isn’t trying to. While China’s state-owned broadband constellation plans are primarily aiming to provide, well, broadband, Geely’s constellation aims to provide enhanced navigation and vehicle-to-vehicle communications. This is particularly interesting because it basically implies that the biggest customer that Geely has in mind for the constellation is….Geely.

Jean’s Take

Another point of interest here is the scale of the production rate: 500 satellites per year, that’s either a very large constellation, potentially several thousand satellites, (which is likely to be operated by Qingdao Shanghe Aerospace Technology, as reported in episode 18), or potentially it could mean that Geely’s satellite manufacturing plant could serve other clients than Geely’s constellation project.

Either way, I think it’s also interesting to note that Geely, a company whose core business remains the automobile industry, is a great candidate to be a “NewSpace smallsat manufacturer”, in the sense that the automobile industry is an extremely competitive, mass-market industry, where the production rate, the optimization of the manufacturing process, and the pressure on lowering costs are critical. Geely produced nearly 1.4 million vehicles in 2019, making it one of the largest automobile manufacturers in China. This experience could serve the company well in its space ventures, to bring costs down and possibly to compete with a growing number of satellite super factories (Commsat, Galaxy Space, …).

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space