SpaceWatch.Global asked its staff and contributors to review 2019 and provide an outlook into 2020. These personal reviews are being published during the holiday season. This is Dr. Malcolm Davis of The Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

By Dr. Malcolm Davis

With 2019 approaching its end, looking ahead to the 2020s, what might be the key developments – and risks – emerging in the space domain?

Focusing in on space in the 2020s, we’re starting off with the establishment of the U.S. Space Force on 20 December 2019. The Space Force will organize, train, and equip the U.S. military to promote space resilience and build deterrence capability to respond effectively against emerging counterspace threats. A key requirement will be to ensure the U.S. maintains freedom of operation in, from, and to space, while providing prompt and sustained space operations.

The focus of the U.S. Space Force is the ‘LEO to GEO’ environment – akin to the ‘brown water’ in the maritime domain. In the 2020s, with the return to the Moon by NASA under Project Artemis, and with the commercial space sector also eying a role on and around the Moon, the question of the relevance of Cislunar space – ‘the blue water’ – to U.S. national security will emerge as one of the most interesting debates in space policy.

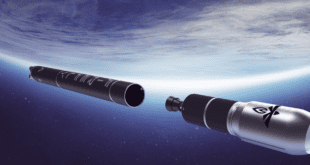

The U.S. Space Force is emerging while China and Russia continue development of a full suite of counterspace capabilities, including direct-ascent and co-orbital antisatellite (ASAT) systems, as well as ground based ‘soft kill’ capabilities. The US and its allies are taking the threat of these capabilities seriously, which is reflected in how key actors are re-organizing military structures with the prospect of warfighting in space in mind.

In looking at the possibility of U.S. and Chinese competition in space at the broader level of national space activity, there is currently no U.S.-China ‘space race’. Yet China’s space program has taken a big step forward with its successful launch of its Long March 5 heavy booster just after Christmas 2019. A Chinese lunar program, building on the establishment of its space station by 2022, and the Long March 9 booster, could coalesce by mid-decade. One scenario to consider might be this: If the Artemis project for a return of U.S. astronauts to the lunar surface by 2024 is delayed by funding shortfalls and in capability development related to the NASA Space Launch System (SLS) booster, how might Beijing react? Its space program has been ‘slow and steady’ so far. Were a chance to beat the U.S. back to the Moon emerge, it would have potentially huge geopolitical prestige for a rising world power intent on challenging U.S. strategic primacy, if it were successful. Would it quicken the pace?

Certainly, the 2020s will see a rapid expansion in the number of space powers, including a broader range of state as well as commercial actors. There are now opportunities for states that previously couldn’t afford their own space capabilities to consider a more ambitious approach to accessing and utilizing the high frontier with their own sovereign capability.

However, this acceleration and expansion of human space activity is occurring against the absence of contemporary international space regulation and space law. The potential for uncontrolled competition between states, or between commercial actors operating independently or on behalf of states, could generate new dynamics that heighten the risk that such competition slides into conflict. So, an increasingly urgent task for major powers is to update, or where necessary, create, new space law and space regulation that manages the prospect of competition, without stifling innovation and progress.

Considering the next decade from the vantage of Canberra, the future is looking rosy. Prospects are opening up for Australian companies to build and launch satellites on locally produced launch vehicles from Australian launch sites, supported by a vibrant but small Australian space agency. Australia’s space sector is surging ahead from the days of passive dependency on foreign providers of space capability, and this is opening up new opportunities for Australia’s defence forces to exploit sovereign space capabilities in the coming decade and to burden-share in orbit. Australia has demonstrated its desire to work with the U.S. on Artemis, signing an important cooperative agreement prior to the 2019 International Astronautical Congress (IAC) worth AUD$150 million to be invested into the Australian space industry sector.

What are the implications of these key developments at the end of the 2010s and going into the next decade? Firstly, in the 2020s, space will emerge as the new domain for strategic competition – it’s no longer just an adjunct to terrestrial geopolitical rivalry. Astropolitics matters. Secondly, space commercialization will open up the prospect for a fundamental shift in globalization as the cost of accessing and using space drops, and the potential for a space-based economy opens up. Thirdly the falling cost of accessing and utilizing space is seeing the rapid proliferation of state and commercial space actors that makes space a more complex, challenging, and dynamic domain in the next decade – that is, of course, much more interesting. It’s a good time to be a space analyst!

Malcolm Davis is a senior analyst at ASPI.