There is a new sector emerging within the space industry that could utterly revolutionise the satellite sector. On-orbit servicing could be the biggest advancement the industry has seen yet as it could bring with it the capabilities to tackle space debris, to repair operational satellites and even upgrade them, reducing the need for new satellites and addressing some of the industry’s greatest challenges. Here, BusinessCom Networks offers up its view on on-orbit servicing.

Taking on the mantel of a satellite operator is not something to be taken lightly. The satellite industry is a tough one. Once you’ve identified your market, you embark on a rigorous design process with a several critical reviews. Then, you build your satellite, which can take years depending on its size and complexity. You test, test, test. Then you must launch the satellite and, once launched, it has to remain in orbit and operational for around 15 years. It’s not for the fainthearted. It is fraught with risk and if something goes wrong, who do you call?

One of the questions frequently asked regarding broadband satellite is why it costs more than terrestrial services. The reason is pretty simple. When installing fibre in the ground, it only has to be performed once. The optical equipment along the path can be upgraded with relative ease, but the big cost, the infrastructure cost, is a one-time or infrequent event. Not so for satellites.

Satellites need fuel to remain in position. Most satellites are in geosynchronous orbit, thus they orbit the Earth at the same rate that the Earth spins, so they remain over a particular location all the time. However, they are still affected by gravity from the Moon, Sun and Earth to some extent, and this can cause the satellite to drift out of position. Propulsion is therefore required to keep them in position. Rather than constantly making small corrections in an attempt to keep the satellite fixed in position, the satellite is put into a small “figure 8” that keeps it locked into a tight position in space using minimal fuel to stay there. All is well for the 10 – 15 years that the fuel normally lasts. When the fuel is nearly depleted, the satellite is sometimes put into a larger “figure 8” referred to as an “inclined orbit,” which requires tracking antenna on the ground (capacity prices are reduced). Eventually the satellite uses up the fuel, but a small amount is saved to kick the satellite out of orbit, into a satellite graveyard, or to burn up in the atmosphere.

But what if the life of these satellites could be extended? And, if there is a problem with the satellite during its operations, what if you could call emergency assistance? This concept is advancing fast. On-orbit servicing could transform the satellite industry as we know it by dealing with refuelling, repairs, upgrades and the like, in space, rather than operators being forced to discard satellites. By extending the life of satellites, the perennial challenge of space debris could also be tackled. Rather than lofting more spacecraft, existing ones can continue their operational life or re-locate them rather than being condemned to the graveyard orbit. Could the savings made by operators through not having to build another satellite eventually make their way down the chain to the end user? It’s an interesting question.

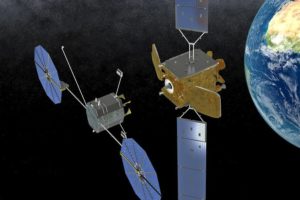

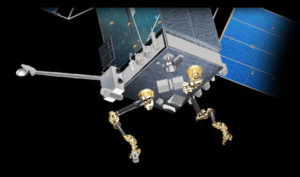

There are a few companies that are pursuing on-orbit servicing. In March of 2018, Orbital ATK announced plans for a next generation of “satellite life extension and in-space servicing products.” These are robotic systems that will bring new options for servicing and enhancing their customer’s satellites. Mission Extension Pods (MEPs) and Mission Robotic Vehicles (MRVs) are new products that will provide clients with the ability to extend the life of their valuable in-orbit satellites. The MEP refuels otherwise operational satellites for another five years, using an external propulsion module that attaches to fuel starved satellites. The primary role of the MRV is to transport MEPs, but it can also be used for some types of repairs. The MEP and MRV are designed to complement Orbital ATK’s first commercial vehicle to service satellites – the Mission Extension Vehicle, or MEV.

MEV-1 is expected to be launched in 2018, along with the Eutelsat 5WB satellite aboard an International Launch Services (ILS) Proton launch vehicle. It will begin providing mission-extension service for Intelsat, Orbital ATK’s first customer. The MEV-1 may be used to service multiple satellites with the same MEV vehicle. The MEV uses a low-risk docking system that attaches to a healthy satellite in need of fuel. It will attach using existing features on the customer’s satellite. Attaching a MEP to the satellite will provide it with another five years of fuel. The MEP will then take over propulsion and attitude control for the ageing satellite.

MEV-1 will also be able to perform inspections and take images that will be sent back for review. The platform will provide the ability to relocate satellites to different orbital slots or different orbits. The company plans to expand capabilities to provide a fleet of on-orbit servicing vehicles with ever expanding capabilities, including repairs, cargo delivery, in-orbit assembly of large space structures, and deep-space gateways in lunar orbit.

Another key company developing on-orbit servicing technology is Space Infrastructure Services (SIS). Set to become operational in 2021, SIS will provide servicing capabilities to GEO customers. The company has entered into a long-term agreement with MDA and SSL to design, build, test and operate the fleet. In terms of their offering, SIS expect to enhance the use of existing space assets through on-orbit inspection in high-resolution imagery, mono and bi-prop spacecraft refueling, repair for deployment malfunctions of antennas and solar panels, upgrade of modules or future plug-in spacecraft payloads, and relocation of satellites for de-orbiting or within the GEO arc. SIS also plans to offer partial assembly in orbit on existing satellites, replacing elements from modular satellites or constructing larger satellites. A single SIS vehicle will have the capability to service multiple satellites per year over multiple years and the servicing time is short and expected to be completed within days, allowing its spacecraft to respond to urgent needs and offering increased flexibility.

There’s no question that this is an exciting development, but it should be noted that some satellite operators are questioning whether it makes sense to give satellites longer lifespans, given the speed at which technology changes. For satellites focused on data communications, perhaps replacement makes more sense? On the other hand, if the primary purpose of the satellite is the basic task of beaming video to the ground, keeping it going as long as possible makes a lot of sense. The ability to provide refresh the technology on a satellite as well as refuelling, could be the real game-changer resulting in cost savings for consumers and more revenue for satellite operators from a valuable asset that sits there generating revenue – just like fibre.