by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 31 January – 6 February 2022.

Welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Space Updates! I’m Jean Deville, joined as always by my co-host Blaine Curcio.

In this episode, we discuss China’s space ambitions through the lens of its latest Space White Paper, but first let’s talk about what looks like a Chinese version of Relativity Space.

1) Are we seeing the dawn of a Chinese version of Relativity Space?

Jean’s Take

As you know, Relativity Space is a US launch company based in California which is known to exploit additive manufacturing (aka 3D Printing) to build its rockets. While 3D Printing is now more and more common practice for making rocket parts, especially for complex rocket engine parts, Relativity Space is rather unique in the sense that they plan to fully 3D print their rockets.

This has advantages according to the company:

- Able to print complex parts that were otherwise either wasteful or impossible to manufacture

- The ability to have a much more simplified supply chain

- automating the manufacturing of a rocket (cut down on costs + production time)

- The ability to iterate and change rocket designs much more easily

So how is all of this related to China? Chinese launch companies, regardless of if we are talking about the state-owned Long March rockets or commercial launch companies (iSpace, Landspace, Galactic Energy, …) generally all use 3D Printing to some degree, but it’s for targeted parts. And this is also generally the case outside of China. Very rare are the launch companies that are all-in on 3D Printing like Relativity Space.

Very rare but… not non-existent. It seems that we may be witnessing yet another launch company seeing the day in China, and this time, the kid in town seems to be adopting a similar strategy to Relativity Space. We are talking about… SpaceTai (or 太瀚航天).

The company was founded in March 2021, and is one of the most recent Chinese commercial launch companies, adding to the very crowded pool of ~15-20 other domestic launch companies competing for the satellite launch market.

SpaceTai has announced that over 90% of its rockets will be 3D printed, and this includes the engines, but also the entire body of the rocket; The figure of 90% is similar to Relativity Space, which 3D prints its rockets up to 95%.

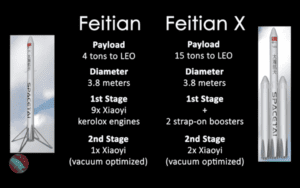

SpaceTai plans to design 2 rockets: the Feitian and the Feitian X:

-

Credits: Screenshot from the DFH show Feitian is a 2-stage medium-lift rocket, putting 4 tons into LEO, has a diameter of 3.80m, and will be powered on the first stage by 9 kerolox engines called Xiaoyi (“Small Ant”); while the upper stage has a single vacuumed optimized version of the same engine.

- Feitian X, which is a heavy lift rocket putting 15 tons into LEO. We don’t know that much about the architecture, but it seems like this will be a sort of Falcon Heavy architecture, with 2 side-boosters providing additional thrust, the rocket body will also be a bit more elongated, and the second stage will have an additional vacuum-optimized engine.

Both rockets would naturally be reusable, performing VTVL.

At the core of any 3D printing rocket company is the mastery and the design of sophisticated 3D printing machines that are able to satisfy spaceflight requirements; and the according software. This is the case for Relativity Space (Stargate, the largest 3D Printer in the world); and apparently, SpaceTai has developed a much more modest printer called the Xingchen S480, and has created a 3D printing rocket parts production line in Xi’an. They are also designing the Xingkong W450, which will be able to print pieces that are 4.5m x 4m. I think that’s below Relativity Space’s Stargate printer, which can print pieces up to ~11m tall, but still a good starting point to 3D print rocket bodies.

How likely is any of this to happen? It’s hard to confirm any of this, the company is very new. It is aiming for a maiden launch in 2024, which is probably a bit (too) ambitious when we look at the time that Relativity Space has taken to do the same (maiden launch is planned for 2022).

In terms of pricing, SpaceTai has said that each rocket should cost 10 million RMB, or roughly 1.5 million USD, for a rocket that puts 4t into LEO. I guess other costs beyond manufacturing haven’t been factored in at this point, but that sounds dirt cheap (375$/kg) but these are just theoretical figures, it will be interesting to see if they are able to maintain these prices once they complete their R&D process.

Also, I’m not sure if SpaceTai has raised any funds (I couldn’t find anything). They do say that they will need ~600 million RMB (100M USD) to reach their maiden launch, which seems like quite a small amount of funding.This can possibly be explained by the fact that they plan to start a rocket parts 3D printing business in 2023 to create an alternative stream of revenue.

Anyway, we will keep you updated on this interesting rocket company, and also very young.

2) China 2021 Space White Paper

Blaine’s Take

Significant piece of news rounding out last week, with the publication of the every five-year China Space White Paper, a document that summarizes the achievements of the previous five years, outlines major tasks for the next 5 years, and discusses the regulatory and policy support mechanisms in place to help achieve these major tasks.

This year’s edition of the White Paper took on a somewhat different tone than previous years, taking a more global perspective in general, and making some bolder claims about the role of space in the coming 5 years. The takeaways can be divided into three main areas: more commercialization and broadening sources of innovation, more international cooperation, and an expansion of the space sector more generally.

The first overarching topic of note was more commercialization, and an emphasis on innovation in the space sector. Historically, China’s space industry has been primarily comprised of a few huge SOEs (CASC, CASIC, etc.), and their subsidiaries, of which there are hundreds. Historically, these companies have produced a large percentage of the components that go into CASC’s missions–rockets require a lot of parts, lunar missions require a lot of parts, and building those parts requires specialization. In the early days of the Chinese space sector, all of that specialization was in the state/SOEs, and even as recently as 5-7 years ago, a huge amount of the supply chain was CASC and subsidiaries.

Since the last White Paper 2016, we have seen a lot more commercial companies enter the market, and several have made some major accomplishments. The White Paper specifically mentioned the Hyperbola-1 and Ceres-1 rockets of iSpace and Galactic Energy, respectively, alongside rockets from China Rocket and Expace. If we compare today with 2016, it’s astonishing to witness the number of commercial companies not only developing systems level products themselves, but developing subsystems-level products.

I think as recently as 2015, it would have been unthinkable to have a company like Jiuzhou Yunjian exist–they specialize in liquid methalox engines, and their main customer base is other commercial launch companies that want to integrate their engines into their rockets. Incredible. Digressing, a big part of the white paper was commercialization and the importance of innovation, whether done by SOEs or commercial players.

→this reflects importance of space sector

Second point is more international cooperation. The White Paper outlines a variety of international cooperation projects completed during the 2016-2021 period, including several successes on the Chang’e-4 mission.

Major international projects moving forward will include the Chinese Space Station and ILRS, Belt and Road Spatial Information Corridor-related projects, and rather specifically, priority funding for developing communication satellites for Pakistan, cooperating on the construction of the Pakistan Space Center, and Egypt’s Space City.

The White Paper also calls for “safeguarding the central role of the United Nations in managing outer space affairs”, which may or may not be a subtle way of saying that no single country can claim reign over outer space, not even the current global hegemon.

Finally, the White Paper makes repeated reference to developing applications using China’s space infrastructure. This has been a theme for a long time, but it’s worth repeating now, because as China launches more and more ambitious space infrastructure, the opportunities to develop applications using that space infrastructure increase markedly.

As noted in the conclusion of the White Paper, “the space industry around the world has entered a new stage of rapid development and profound transformation that will have a major and far-reaching impact on human society. At this new historical start towards a modern socialist country, China will accelerate work on its space industry”. Quite a lot to look forward to in the coming years!

And with that being said, this week saw the beginning of a New Year in China, and some New Years greetings from a diverse cast of characters in Chinas’ space program.

3) Conclusion (Chinese New Year)

Blaine’s Take

This week saw the arrival of the Year of the Tiger, with Lunar New Year celebrations taking place across China and elsewhere. In addition to the usual mass migration of people (made somewhat less mass by covid), the New Year’s Gala, and family gatherings, we saw this year some cosmic New Year’s Greetings sent from China, and the people and robots that make up its space infrastructure.

First, we saw some videos sent by the three taikonauts onboard the CSS conveying their Chinese New Year greetings. In addition to an impressive amount of red paper and other CNY essentials (it’s hard and expensive to launch all that into orbit!), we saw smiles and festivities from the surprisingly roomy-looking Chinese Space Station. The Shenzhou-13 crew, comprised of Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping, and Ye Guangfu, is a bit more than halfway through their ~6 month stay on the Chinese Space Station. Scheduled to come back to earth in around April 2022, before the Shenzhou-14 crew, and possibly before or after the Tianzhou-4 cargo mission, which will be launched in advance of the Shenzhou-14 crew.

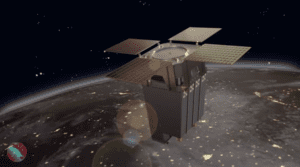

Second, we saw a message delivered from considerably further than low-earth orbit, namely some amazing selfies and videos taken by the Tianwen-1 spacecraft, currently orbiting around Mars and supporting the Zhurong rover there. The camera was supported on a narrow, 1.6m long (possibly robotic?!) arm that was attached to the Tianwen orbiter, and is normally used by the CNSA to monitor the health of Tianwen. The video itself is stunning, with some incredibly cool images of Tianwen-1, its prominent solar panels, and various instruments onboard the orbiter. Throughout the video, you can progressively see Mars getting closer and closer, before finally getting a pretty full-on view of the ice-covered north pole of Mars. Pretty amazing to watch the video and think that somewhere down there on that sparse planet is Zhurong, roving around sending signals back to earth via Tianwen (or in some cases the ESA Mars Express).

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.