by Blaine Curcio and Jean Deville

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 19 – 25 July”.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch.Global and Orbital Gateway Consulting we have been granted permission to publish selected articles and texts. We are pleased to present “Dongfang Hour China Aerospace News Roundup 19 – 25 July”.

Hello and welcome to another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup! A special shout-out to our friends at GoTaikonauts!, and at SpaceWatch.Global, both excellent sources of space industry news. In particular, we suggest checking out GoTaikonauts! long-form China reporting, as well as the Space Cafe series from SpaceWatch.Global. Without further ado, the news update from the week of 19 – 25 July 2021.

1) China’s first space-based solar station experimental base begins construction in Bishan District, Chongqing

Jean’s Take

China kicked off the construction of its first space-based solar station experimental industry base in Bishan District of Chongqing. Chongqing is a city in southwest China, and is actually one of the four provincial-level municipalities of the country alongside Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin. According to a report by Chongqing Daily, 2.6 billion RMB (roughly 400 million USD) should be invested into this base, and will cover 200 acres/0.8 km2.

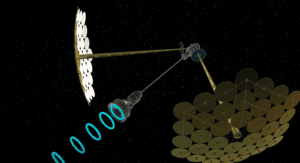

This experimental base will aim at demonstrating the feasibility of space-based solar harvesting, and notably technologies such as the space-to-ground transmission of energy through microwaves.

Let’s just give a recap on what space-based solar stations are about. The idea, which dates back to the 1970s, stems from the fact that solar stations on Earth are hampered by the presence of clouds, which can block sunlight and make solar panel effectiveness drop significantly. Even when there are no weather issues, there is always some level of atmospheric absorption, and more importantly, solar panels are only able to work during daytime, in other words 12 hours a day on average.

Let’s just give a recap on what space-based solar stations are about. The idea, which dates back to the 1970s, stems from the fact that solar stations on Earth are hampered by the presence of clouds, which can block sunlight and make solar panel effectiveness drop significantly. Even when there are no weather issues, there is always some level of atmospheric absorption, and more importantly, solar panels are only able to work during daytime, in other words 12 hours a day on average.

Now if we put this solar station in space, all these problems are lifted: the solar station benefits from a continuous 24/24 amount of sunlight, without the attenuation from clouds or atmospheric effects.

Of course, things are never that easy, new problems arise:

First of all, solar stations are heavy if you’re planning to generate enough power to be significant on the ground (say to power a district for example, …). You need huge surfaces of solar arrays, and powerful microwave transmission systems (SSPA, TWTA, …) to transmit this energy.

China plans to send a MW-level experimental space-based solar station in 2030, and according to a researcher from CAST in 2020, a MW-level solar station would weigh 200 tons. That is unimaginably heavy, and inaccessible for currently operational launch vehicles.

On a more positive note, China is developing the Long March 9 and Long March 5DY for crewed lunar exploration, two new rockets with the ability to put up to 150t and 70t into LEO respectively, according to the latest iteration of the rockets presented by Long Lehao, the chief engineer of Long March rockets at CALT.

Fun fact, Long Lehao actually suggested during a speech at HKU in June 2021 that space-based solar stations could be one of the uses of China’s lunar rockets. He showed notably a table with estimations of solar station masses and corresponding number of launches:

- We can see that a MW level station with a lifespan of 15 years would weigh 660t, and would require 17 Long March 9 launches to be assembled, and this plans to be done in 2030.

- Then there would be the GW-level station with a lifespan of 30 years at 10 000 tons, and would require 143 launches of Long March 9 to be assembled!

Definitely sounds like science fiction in 2021, but hey, the GW level station is planned for 2050, in 30 years. Perhaps rocket reusability will have made progress to enable launch prices to go down sufficiently to make such a project economically viable.

Also, this sort of technology could be very interesting for space exploration, for power generation on a Moon or Mars base for example.

Back to feasibility considerations, beyond the massive payload weight, there are other problems of course with space-based solar stations, such as the efficiency of the transmission systems, the size of the receiving stations on the ground, and actually much more than that. If you’re interested in China’s space based solar stations, and just China’s funkier space projects, we have an episode dedicated to that, called “The Most Funky Space Projects in China”.

Blaine’s Take

This project is indeed fascinating. Perhaps to give a little more insight on the timeline that China has in mind:

- China has had space solar power systems on the roadmap since 2008 when the technology was added to a national-level preliminary research plan.

- The decision of having the first industrial base on this technology located in Chongqing was made in 2018, and construction has been underway since last month. Players involved are notably Chongqing University, Xidian University, and CAST’s Xi’an, with the project being under the leadership of Chinese academician Yang Shizhong.

- According to the recent report by the Chongqing Daily, the next step would be a first small scale prototype to be sent into the stratosphere (altitude of 10-50 km), which is above clouds and the most dense parts of the atmosphere. This would be achieved by 2025.

- The next steps are not detailed by the Chongqing Daily, but would be larger scale prototypes, and this brings us back to the MW-level station in 2030 and the GW-level station in 2050 mentioned by Long Lehao.

- Final point on this specific project–one of the most entertaining parlor games that space industry folks can have nowadays is the question of “what kind of new businesses or technologies will be enabled by a massive decrease in launch costs?” This could be anything from fleets of IoT cubesats for big companies (John Deere recently expressed interest at a low enough price point), space tourism for the world’s 1%, or indeed, space-based solar stations. While completely inconceivable with the rockets of today, much less several years ago, we may see space-based solar stations become a reality in part due to much lower launch costs.

Taking a bit of a step back, it’s probably worth noting the impressive space industry cluster that has developed in Chongqing over the past couple of years. In addition to the space-based solar power station project, Chongqing is also a major hub for CASC’s LEO broadband constellation efforts, including its subsidiary China MacroNet (东方红卫星移动通信有限公司), which announced an expansion of its efforts in Chongqing at the end of last year. More recently, we saw China SatNet leadership meet twice with the Chongqing Municipal leadership over the course of ~1 month, announcing somewhat vague collaboration agreements with the city.

Over the next several years, with an urban population of more than 10 million, a municipal population of more than 30 million, and a somewhat greater degree of autonomy due to being a Provincial-Level City, we may well see Chongqing continue to develop a bustling space cluster.

2) Chinese EO satellites to the rescue in the aftermath of Henan’s catastrophic floods

Jean’s Take

As most viewers and listeners are probably aware of, over the last week China’s central province of Henan encountered record-breaking amounts of rain, starting on July 17th, and considered to be once in 1,000 year-level of rain, triggering devastating floods.

Summer is generally the rainiest time of the year in Henan, but this time the concurrence of several additional climatic factors, including the massive moisture pushed onto the Mainland by typhoon In-fa, turned what could have been an unremarkable downpour into the perfect storm.

The epicenter was the city of Zhengzhou, which literally experienced the amount of an entire year’s worth of rainfall in a single day, on July the 20th. And the consequences were severe, we’ve all seen the images of the roads of Zhengzhou turned into river torrents, passengers trapped in the subway, as well as cars piled up as the water slowly withdrew.

The point of this episode is not really to discuss the consequences of Henan’s deadly floods, although Blaine and I definitely pay our respects to those that have been affected by the disaster.

Rather, I want to focus on how EO, and notably Chinese EO companies, are putting their resources and efforts into providing remote sensing data on Henan and turning it into intelligible analytics for the local government, insurance companies, and rescue teams:

Four Squares Technology for example ordered SAR imagery from China’s Gaofen-3 satellite, a satellite launched in 2016 and that is part of the state-sponsored program China High-definition Earth Observation System (CHEOS). SAR data is notably good at picking up still water (they appear dark on images because the radio waves are specularly reflected, meaning that they are reflected away from the radar sensor). This enables Four Squares Technology to clearly detect the amount of flooding and the areas that are most affected.

- Jiahe Info, a remote sensing data analytics company based in the neighboring province of Hubei, in Wuhan, adopted a similar strategy, going for Gaofen-3 SAR data. They have notably been processing the images using their data analytics algorithms to extract useful information for agriculture insurance, enabling farmers to quantify the damage and claim compensation.

The way this is done is, radar signals are reflected differently depending on the wetness of the soil, the consequence of this is that SAR can determine farmlands that have been soaked to an extent where the crops are no longer able to survive.

Interestingly, Jiahe Info has decided to provide this service for free for all disaster-stricken areas of Henan, something that will definitely be appreciated by the local farmers. - Xinde Zhitu (信德智图), another data analytics company based in Beijing, is also doing a similar thing with GF3 data and for crop insurance in Henan, also for free.

Perhaps more interestingly, they posted a table of EO satellites that would be used for the disaster. There’s the Gaofen 3 SAR satellite, but also other Chinese leading optical satellites: the Gaofen 1, 2,and 6, 21AT’s Beijing-2 optical satellites, China Siwei’s SuperView satellites, Charming Globe’s Jilin-1 EO constellation, and…US-based company Planet’s EO constellation data. It’s interesting to see that California-based company Planet’s images are being used for disaster relief on the other side of the planet (no pun intended).

Blaine’s Take

Great word–specularly. 20cm in 1 hour

Another satellite that was very helpful for monitoring the evolution of the situation in Henan was China’s Fengyun-4 meteorological satellites. Situated in geostationary orbit, they are able to take images at a high frequency due to their permanent position above China, as opposed to other satellites in SSO which have a revisit periodicity of once every 12 hours. High frequency images are notably useful for monitoring the evolution of violent climatic phenomena like typhoons. For a more in-depth deep-dive of Fengyun, check out the Dongfang Hour Episode 36 from last month, when we do a deep dive into all things GEO meteorology satellites in observance of the recent launch of Fengyun-4B.

In addition to the various EO satellites that played a role in helping the people of Henan, we saw a number of articles published by China’s satellite telecom companies (ChinaSat and APT Satellite, primarily) discussing the role that they played in flood response. This included providing critical communications to places that had lost their connection with the outside world. As we noted a few months ago on the DFHour, China has a major emergency communications conference and exhibition every year. At this year’s edition, we saw a number of satellite equipment manufacturers release satcom products designed for emergency comms, for example new Ka-band terminals to connect emergency vehicles. For a more detailed look at the involvement of China’s satcom companies, be sure to check out the DFHour Newsletter from this week.

Moving forward, it will be interesting to see whether the events of this week’s flooding in Henan lead to even more emphasis on emergency response by China’s satcom industry, or potentially the government more generally.

3) A Long March-2C Launches a handful of satellites

Blaine’s Take

On 19 July, a Long March-2C rocket launched the latest trio of Yaogan SIGINT satellites, along with the Tianqi-15 satellite from Guodian Gaoke. This is but the latest Yaogan launch of 2021, with China having sent a whopping 19x Yaogan satellites into orbit this year (7 launches, of which 6 were triplets and 1 was a single Yaogan satellite).

Worth noting, a parachute system was added to the first stage of the Long March 2C, as a way to perform a controlled reentry. The launch took place from the Xichang launchpad in the landlocked province of Sichuan, Western China. This generally means that the first stages come crashing down into rural but possibly inhabited areas of China. While the launch teams generally make calculations on the potential landing area and evacuate the populations in those areas, there is still a fair amount of uncertainty, which is where first stage parachutes can play a role to reduce the landing zone ellipse.

As is becoming quite normal, the TT&C services, at least for the Tianqi satellite, were provided by Satellite Herd. The company has done very well to build out a global network of TT&C stations, including recent deals announced with Azerbaijan and Argentina, and they now provide TT&C services to a significant percentage of the commercial satellites launched by China. Also of note is that unlike most Chinese commercial space companies, which tend to be in CAPEX-heavy industries with long R&D development time (takes a long time to develop a rocket), Satellite Herd is in a less CAPEX-intensive industry, with a far shorter development timeline. This means that they are currently revenue-producing, and may even be profitable (though their rapid expansion internationally likely means that a lot of their revenues are being plowed back into building out their network).

While the Tianqi-15 nanosatellite was only the secondary payload here, it’s worth highlighting that this marks the completion of the first stage of the Tianqi Constellation. Let’s expand on this a little:

- Tianqi (also translated in Apocalypse) is a 38-nanosatellite IoT constellation project of Chinese commercial company Guodian Gaoke. The constellation plans to serve verticals such as smart agriculture, environment conservation, power grids, coal mining, container transportation and other such industries that need to deploy a plethora of sensors to monitor the state of various parameters.

- These applications are generally situated in remote areas, and don’t need high frequency updates. Guodian Gaoke claims to now have 14 operational satellites in orbit, enabling a fly-over every 1.5 hrs (and consequently an update of a given sensor’s status). This frequency is deemed sufficient for most applications of industry verticals targeted by the Chinese company, thus completing the “first phase” constellation deployment that enables the commercialization of the Tianqi satellite services.

In a second step, Guodian Gaoke aims at completing the entire 38-satellite constellation by the end of 2022, enabling more receivers on the ground to be connected as well as shorter revisit times. It is also interesting to note that at the moment, China does not have a state-owned global LEO narrowband constellation. In the west, we have had the Iridium constellation for some time, which provides narrowband communications for similar verticals to Guodian Gaoke. More recently, Iridium launched its NEXT generation of satellites, which provide somewhat higher bandwidth (though you still would not want to rely on Iridium for Netflix streaming). In China, the Xingyun constellation, being developed by CASIC, is conceptually quite similar to Iridium, and to some extent Guodian Gaoke, in that it plans to address narrowband communications.

In a comment about the speed of Chinese commercial space, we have now seen a couple of Xingyun satellites launched, and in the same timeframe, Guodian Gaoke has completed their first-phase constellation. Undoubtedly, part of this comes from the general speed of China’s commercial space companies. Another factor alluded to in the above-linked article is Guodian Gaoke’s cooperation with local/city governments. As the article notes, there was an event with the cities of Jiaxing (Zhejiang), Yan’an (Shaanxi), and Ruijin (Jiangxi), in collaboration with Guodian Gaoke. While the collaboration between these parties is a bit nebulous, generally speaking having city governments on your side in China is a good business practice. Looking forward to seeing more accomplishments from Guodian Gaoke!

Jean’s Take

I think this is exciting news because we are seeing China’s first commercial constellations to actually take shape and begin to commercialize (another such constellation would be Jilin-1 of CGSTL, …). There have been so many constellation projects in China, since 2014 I believe there have been at least 20 of them. Quite a few haven’t been able to materialize for funding reasons, others for regulatory reasons, and some were simply just PPT/slideware constellations. But it’s nice to see that there are also some solid projects out there, and Guodian Gaoke’s Tianqi constellation definitely seems to be one of them.

This has been another episode of the Dongfang Hour China Aero/Space News Roundup. If you’ve made it this far, we thank you for your kind attention, and look forward to seeing you next time! Until then, don’t forget to follow us on YouTube, Twitter, or LinkedIn, or your local podcast source.

Blaine Curcio has spent the past 10 years at the intersection of China and the space sector. Blaine has spent most of the past decade in China, including Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Beijing, working as a consultant and analyst covering the space/satcom sector for companies including Euroconsult and Orbital Gateway Consulting. When not talking about China space, Blaine can be found reading about economics/finance, exploring cities, and taking photos.

Jean Deville is a graduate from ISAE, where he studied aerospace engineering and specialized in fluid dynamics. A long-time aerospace enthusiast and China watcher, Jean was previously based in Toulouse and Shenzhen, and is currently working in the aviation industry between Paris and Shanghai. He also writes on a regular basis in the China Aerospace Blog. Hobbies include hiking, astrophotography, plane spotting, as well as a soft spot for Hakka food and (some) Ningxia wines.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space