On 22 April 2020 Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) successfully launched a small satellite – the Noor-1 (Farsi for ‘Light’) – on a previously unseen satellite launch vehicle called the Qased. Over the course of this week SpaceWatch.Global is running a series of perspectives on the strategic, political, and geopolitical implications of the launch for Iran, the Middle East region, Europe, and the United States. Today’s perspectives come courtesy of Fabian Hinz, Research Associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California, United States (below), and Tal Inbar, a leading Israeli expert on space and missile programmes (see here).

What are the strategic implications of the launch for European and US security?

In terms of the Noor reconnaissance satellite itself, the launch does not have major implications for European or US security. We still don’t know whether the satellite is fully functional and even if it is, it won’t offer real advantages over commercial satellite imagery available on the free market.

However, the Qased launcher, the way the launch was conducted and the institutional arrangement that developed the Qased seem to introduce a new dynamic to Iran’s space program. We can expect to see a gradual move towards SLV technology that is much more militarily viable than Iran’s previous launchers and thus poses a direct challenge to European and US security interests.

What can you tell us about the Qased launch vehicle?

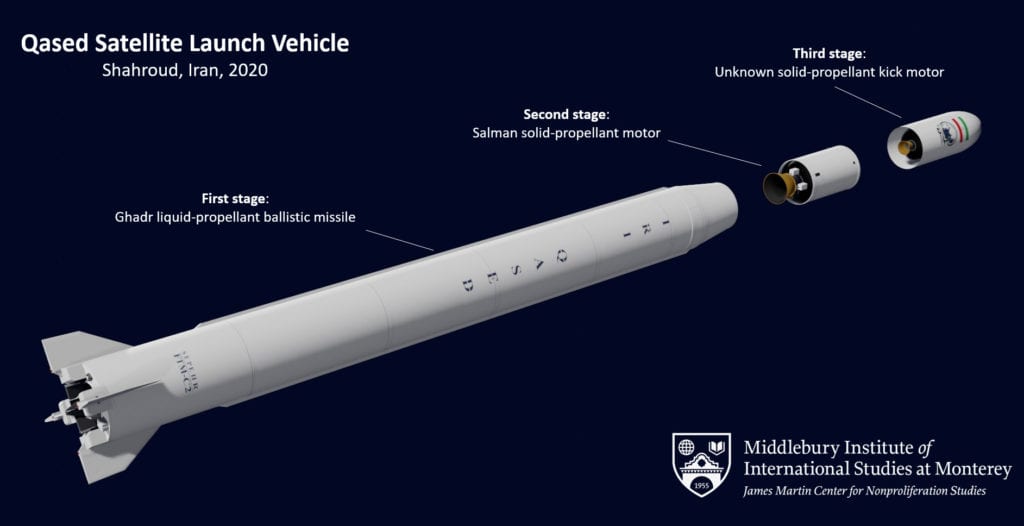

Iran’s Qased is a three stage system, using a well-known liquid-propellant ballistic missile called Ghadr, an upgraded version of the Shahab 3, which is Iran’s version of the North Korean Nodong.

The use of Nodong technology in itself is not too extraordinary, Iran’s previous SLVs, the Safir and the Simorgh, use the same technology for their first stages.

The second stage is where things get interesting. Both statements by Iranian officials and footage released show it uses the ‘Salman,’ a recently unveiled IRGC-developed solid motor. While the Salman is relatively small in dimension, it uses sophisticated technologies like a light-weight carbon fiber motor casing and a swivelling nozzle for thrust vector control. Of course, these technologies are also highly relevant to the development of longer range ballistic missiles.

Details about the third stage are a little hard to come by. Some statements indicate it might be small solid propellant motor, whether it is one of the previously unveiled Iranian systems or a new one developed the IRGC is not entirely clear.

The Qased itself, using old technology for its first stage and being quite limited in performance might not seem that worrisome at first. However, if one takes a closer look at the institutional setting of the program and statements by IRGC officials, it becomes clear that the Qased is not standalone system but rather the inauguration of an IRGC’s solid-propellant SLV program. IRGC Aerospace Commander Hajizadeh has declared that the use of a liquid-propellant Ghadr for the first stage was a mere testing arrangement and that future SLVs would be all solid-propellant. Satellite imagery of solid propellant motor testing at Shahroud indicates that work on larger diameter solid-fuel motors might already be well underway.

Are US allegations that the Iranian space programme is merely a cover for its ballistic missile programme fair, or does the US have a point?

Here one really has to differentiate between two branches of Iran’s space efforts. There is Iran’s overt program, which we have been observing for more than a decade now, with Iran’s first satellite launch in taking place in 2009. This program relies on Nodong technology and Soviet R-27 technology for upper stages, which has obvious limitations for long-range missile development. An ICBM developed from Iran’s Simorgh would simply be too large, immobile and would take too much time to fuel to be a viable weapon in a theatre dominated by the US air force.

So in short, the overt program might rely on tech derived from ballistic missiles and its launchers are built by the same organizations but missiles are more of a starting point rather than the end product of the program. There are still some military benefits to be gained from Safir and Simorgh launches, in terms of gaining experience with staging, telemetry etc., but these seem more like side effects than actual goals of the program,

Now the second track is the IRCG’s space development effort and here things look a little different. As mentioned before, the program focusses on solid-propellant technology which is much more viable for military applications. Add to this that the program ran in secrecy for about fifteen years and that IRGC officials have commented about “various dimensions of the program” and “an important deterrence role” of the project. Taken together, the IRGC’s space effort looks a lot like a hedging strategy to acquire technology usable in missiles with ranges beyond Iran’s voluntary 2000km limit.

Why do you think the IRGC has created its own Space Command?

Iran has both a regular army, the so-called Artesh, and the separate Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The IRGC not only serves as the Islamic Republic’s praetorian guard but has also amassed significant political and economic power within the country. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the IRGC would try to gain control over an asset as strategically important as space capabilities.

Judging from the statements of IRGC officials, their long-term goals in space are highly ambitious. The IRGC Aerospace Force Commander, as well as the Space Commander have both mentioned plans for further reconnaissance satellites, communication satellites and even navigation satellites. In practice, however, such plans will be constrained by formidable technical challenges, the time frame required for such programs and, above all, by the Islamic Republic’s massive economic problems.

In your opinion, how should the US and European countries respond, if at all, to the IRGC space programme?

When it comes to Iran’s missile program, the West is in danger of repeating the same mistakes it made with North Korea. For years, the US was obsessed with every short-range missile test the country conducted and with a North Korean space program that used the same technology as Iran’s Simorgh. In other words, they focused on present and visible capabilities instead of more destabilizing but abstract future capabilities. Then, in 2017, seemingly out of nowhere, North Korea tested two types of ICBMs it had been working on in secret for years.

Iran is about as likely to give up its short- and medium-range ballistic missile program as the US is to give up its Air Force. The country’s Safir and the Simorgh SLVs, as mentioned earlier, are of extremely limited military usefulness. Instead of beating dead horses, the West should put its focus on preventing the emergence of long-range missile technology. But then again, with the IRGC program now operating in the open, and US-Iranian relations in freefall, even retaining the 2000km range limit and preventing the use of militarily useful technology in spaceflight might be too ambitious of a goal at this point.

Fabian Hinz is a Research Associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. In his work he focuses on the use of Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) for analyzing Middle Eastern missile proliferation.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space