Since a very young age, Michaela Musilova dreamt of exploring space and eventually becoming an astrobiologist to find the answers to the ultimate question: is there life out there? Today, as Chair of the Slovak Organisation for Space Activities, Musilova has tirelessly pursued her dream and, from the 8-year old girl that found herself inspired by a trip to the NASA Goddard Flight Center she has become a successful astrobiologist in her own right, teaching young people in her native Slovakia and inspiring the next generation of space scientists and engineers. Musilova has a fascinating story to tell and I was fortunate enough to sit down and speak with her. I am sure you will be inspired as much as I was.

Can you begin by telling us more about yourself and your background? Where does your interest in space come from?

My interest in space started when I was about 8 years old. My parents took me to visit NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and I was able to put on this makeshift space suit. I still have a picture from that time which hangs on my parents’ refrigerator door and it reminds me of this childhood dream I had of becoming an astronaut. That dream pushed me forward to do something in space but my family is not from a scientific background. My mother is an archaeologist and my father is a diplomat, so I was more disposed to study languages, history and culture. Then, at 15, I watched James Cameron’s Aliens of the Deep, which is a documentary where scientists and astronauts dive into the depths of oceans and find all of these amazing creatures, which kind of look like aliens. It was that film that reminded me of my passion for space and for trying to find other life out there. I realised that I would never really be happy if I did not go after my childhood dreams – astrobiology..

It was difficult to pursue at that time because astrobiology didn’t really exist as a science or something you could study at university. So, I found the best universities in the UK and the U.S. where I could study something similar, such as planetary science or astrophysics. I started to work during my high school years, to earn money to be able to get into these schools. I got a number of scholarships and I ended up getting into University College London where I studied Planetary Science but even then the fees were too much for me so I ended up with three part time jobs to fund me – it was very difficult!

The good thing about it was that it pushed me to get the best possible grades and the best scholarships, and all of this led to me getting selected in my second year to be one of two students from England to study at the California Institute of Technology. It’s there that I was able to take on some more biology-related subjects including environmental science, microbiology and so on. I found out that there was someone doing astrobiology research at NASA JPL. I contacted him as I wanted to get involved in some way but at that time foreign students couldn’t work for NASA. So, we had to find another way and ultimately, I got a grant to work at NASA JPL as a visiting researcher and I spent some time there in the Planetary Protection Division. We were trying to find ways of minimising the amount of microbes that you could accidentally transport on something like the Curiosity Rover to another planet. They were preparing Curiosity at the time so I even got to put my signature in it, which is now on Mars, a little bit as a reward for the work I did there.

After that, I returned to the UK and proposed a Masters project on astrobiology looking at radiation resistant microbes that we find in places such as Antarctica, which could be analogues for potential life on Mars. My PhD research at the University of Bristol was continued down these lines looking at life in very cold environments as analogues to life elsewhere, even on Europa for example.

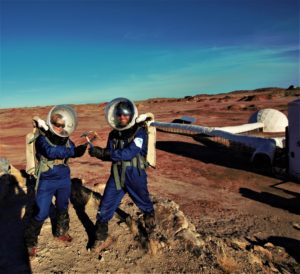

It was that research that got me to go to various extreme expeditions and after studying these extreme lifeforms, I found that some are actually capable of producing a lot of organic matter that could potentially fertilise soils. That’s when I thought of a project that could involve terraforming Mars, where this technique could be used to potentially fertilise Martian soil. This was one of my projects that got selected to be performed at the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah, which is a simulation facility run by the Mars Society. I was also selected as part of a crew of “marsonauts” at the time. I was the GreenHab officer and I was in charge of various research projects during the mission. That was my first experience (in 2014) of going into a simulated mission to Mars, as part of Crew 134. In 2016, I was selected as Commander of another international mission to go back to the Martian facility in 2017. All of the Crew 173 were alumni of the International Space University (ISU). We brought various experiments with us including a lot of research projects from Slovakia and some student experiments – we ran a competition in Slovakia, called “Misia Mars” to select the best projects to take with me.

After finishing my PhD, I started working for Mission Control Space Services, which is a Canadian New Space company. I am still a senior research advisor for them and I also spent time at the ISU, where I now teach.

Can you tell us more about the NASA HI-SEAS mission in Hawaii that you will shortly participate in? How was the selection process and what will the mission focus be?

The HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) mission is requested by NASA, funded by NASA and run in collaboration with the University of Hawaii. This is the sixth mission of its kind. The most recent mission was eight months long and that happened last year. This mission, which will begin in February and run for eight months, is very much focused on crew psychology and how to choose the right crew that will be able to survive all the difficult conditions on a mission to Mars.

There was a worldwide call put out in August 2016, where anyone could apply to participate and then there were multiple rounds where they slowly eliminated people. I am not sure how many people initially applied, but I think there was around a thousand or more. Eventually they chose six of us for the final crew. It took around 14 months for us to find out the final results and then the interviews were varied from filling in online questionnaires to actually doing timed tests and online interviews. It was pretty challenging and there was a lot of waiting involved. Now we are getting ready. I’m planning on taking some experiments from Slovakia with me to the mission and one of them includes a Slovak rover. There is a team from the university where I work preparing a rover to assist me with my research.

The schedule during the mission will all be based on astronaut schedules. We will be told when to wake up, when to go to sleep and we’ll have dedicated hours for various activities. Apparently there’s going to be an hour and a half of exercise every day, which I was thrilled about because I do that already. They have told us that we have been selected based upon astronaut criteria so again, this helps me towards my childhood dream of perhaps becoming an astronaut one day and that I still fulfil this criteria in the eyes of NASA.

Is that something you still want to pursue?

Yes definitely. One of the main problems is that I wouldn’t be able to apply if there was a call because Slovakia is not a member of ESA yet. However, I hope it may be possible if Slovakia could become a member in the near future, or if it becomes possible through the commercial space sector.

Tell us about current space activities in Slovakia and your role at SOSA?

In 2015, I got an offer from the Slovak Organisation for Space Activities (SOSA) asking whether I would be willing to go back home to Slovakia to help push the space sector forward. I decided to do that. My big dream was also to establish astrobiology in Slovakia, which did not exist at the time. So for the past two years, I have been back in Slovakia and I have become the Chair of SOSA. I was also elected as Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology of the Slovak University of Technology. There I have been establishing astrobiology and am helping to teach various subjects on space technology.

With SOSA, we have created an incubator at the University, where we are giving the opportunity to students to work on space-related projects. We provide them with facilities to work there, we provide mentoring and help them get involved in international space-related projects. We’ve also established another incubator at Faculty of Aeronautics of the Technical University of Kosicein Slovakia. On top of this we have a few ongoing projects of our own, such as performing scientific and technical experiments on stratospheric balloons and developing sub-orbital rockets called ARDEA. Those are our current big projects.

SOSA is also responsible for having pushed Slovakia to become a collaborating member with the European Space Agency, as it has been lobbying and doing outreach in Slovakia for almost 10 years trying to convince the public and politicians that it’s worth investing in the space sector, and to convince the ministries to find an agreement between Slovakia and ESA. We are working in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, which is in charge of space-related activities in Slovakia. This agreement was signed in 2015 and Slovakia entered the so-called PECS (Plan for European Cooperating States) programme with ESA in 2016. Potentially, by 2020 or 2021, we can either become an associate member state of ESA or a full one.

Another big SOSA project was to design and develop the first Slovak satellite – skCUBE – which was successfully launched into orbit on June 23 2017. This was a huge project for us because it was essentially achieved completely on a volunteer basis, as SOSA is a non-profit organisation. There were amateurs and students involved, as well as researchers and engineers. In the end, we had approximately 30 companies, three universities and people in and out of Slovakia who contributed to the project. We also gradually got some government funding to help finish the project and help with the cost of the launch. It was a big, inter-disciplinary effort involving everyone from the government and private companies to non-profit organisations. The project is still ongoing. We are still getting data from the satellite and that is being analysed at different universities in Slovakia.

SOSA is also helping to create spin-off companies and start-ups in the space sector. The approximately 30 companies that got involved in the satellite project are now all in some way involved in the space sector, as well and it is also growing thanks to this collaboration with ESA. The skCUBE project leader, Jakub Kapus and myself, we have recently founded a start-up company called Spacemanic. It is a small satellite mission integrator, focused on delivering innovative and reliable nanosatellite solutions, platforms and components. Our engineers are also very experienced in the field of radio communication, and ground station design and operations. Spacemanic was created based on the unique and now space flight proved technologies we developed for skCUBE.

Is there a good level of interest in space and space activities amongst the Slovak population?

Is it still emerging. In in the first few years of space-related activities in the country, people were very sceptical and were asking why should we get involved in space in Slovakia? What is it good for? Even nowadays we are met with these questions when we present at different events or do interviews. However, because we were successful with the satellite and my research and missions have been fairly well covered by the media, they know that we do have potential in this sector and that we should be more involved in it. Public opinion is changing but is still in this mid-stage where people are a bit sceptical about what the benefits are of being involved in the space sector.

In many countries, there is a shortage of scientists and engineers to work in the field of space. Is this also a problem in Slovakia and how does SOSA intend to inspire more young people, and more women, to explore space as a career?

We have a lot of really good scientists and engineers coming from Slovakia but the problem is that the opportunities tend to be much better outside of Slovakia. We probably have the biggest brain drain in all of Europe, in terms of percentage of population – possibly one of the highest in the world. Young and talented people tend to get into universities abroad in the UK or U.S. The Czech Republic is also a prime place for our brain drain too. So while we have a lot of talent, they don’t tend to stay.

At SOSA we are trying to create opportunities for these talented people to get involved in space activities in Slovakia, so they don’t feel that they have to run away elsewhere in order to be able to work in the space sector. Around 30 young engineers were involved in the skCUBE project and now, in SOSA, we have around 100 members of which the average age is around 25-30 years – young people who are very enthusiastic and working on a volunteering basis. That is one of the only ways of doing it unless they study astronomy and astrophysics at university. There’s very little space engineering going on and we’re now currently involved with the main providers through the incubators.

The way we try to inspire young people is first of all to show them that they can do it in Slovakia or we show examples of people like myself who did go away to gain the relevant skills, but came back to try to spread the message about space in our home country. We work with a lot of young people who are at DLR or at NASA or ESA, who still actively collaborate with us, and come back to Slovakia and give presentations and talk about their opportunity abroad, and how they can contribute to Slovakia despite no longer living here. They inspire other young people. We do a lot of outreach. We’re involved in over 100 different workshops, activities and presentations every year and we are in the media on average about once a week at least through interviews and programmes.

Indeed there is a shortage of women in the space sector. I would say it is around 70% male dominated if not more. That’s a personal goal of mine. I feel it is vitally important to do outreach and to show that young women can achieve whatever they set their heart to. We should not have stereotypes in mind and think that space, and generally STEM subjects are only for men. Ever since I have been doing this, I have noticed that I get a lot of messages from young girls and women saying how I opened their eyes and inspire them. We also have a lot of young women active in SOSA. Education and communication are really key to changing the status quo.

Do you think that the NewSpace movement is going to help to Slovakian space industry? Space is becoming more accessible. Small satellites have advanced so much in their capabilities. Do you think it could be a catalyst for a country like Slovakia to come out as a space faring nation?

Yes, I think so and I am very grateful for the whole nanosatellite element. Thanks to this, we were able to build our own satellite. Before that, I couldn’t imagine raising enough funds to build a classic satellite. It would have taken many years and so much extra effort. We were able to build the satellite ourselves. It was built from design to the finished product all by our engineers. The satellite itself was a technological experiment because we came up with around 20 unique technologies within the satellite itself. A lot of the technologies that we demonstrated on the satellite are now being sold on the CubeSat market, such as sun sensors. I think this has really helped us in Slovakia to get involved in the space sector and it’s opening up more and more doors, not just here but all over the world in countries with limited resources. They can have access to space too.

Are there any plans for a new satellite?

Yes, actually. We definitely want to move forward and if all goes well it will be a CubeSat again but this time a 3U CubeSat with a very different experiment on board. There are two options on the table in terms of how to proceed with this. One is to go down the lines of skCUBE 2, which will mean to start again with the fundraising and visiting universities and companies – the same process. Considering the success of the first project, it might not take quite as long and we also have all the important knowhow on how to build the satellite and test all the equipment, so it will be quicker to build. The other option is to build a joint Czech and Slovak satellite. Colleagues from the Czech Republic are very interested in the expertise SOSA has and so the CubeSat could be built in conjunction with researchers and technicians from the Czech Republic. We’re not sure yet which way we will go, but we are evaluating it and we are on the path to getting started very soon.

Finally, what are your hopes and dreams for SOSA and for Slovakia in space?

One of my main hopes and dreams is that we will become a full member of ESA in the near future. In the meantime, I hope that in SOSA we will continue with all the knowhow and experience we have from the satellite development and to build new satellites. I would also love to see us involved in an astrobiology mission sometime in the future with astrobiologists here in Slovakia. I am hoping to mentor the next generation of astrobiologists here, so that’s one of my personal goals. Generally speaking, I hope that Slovakia will grow in the space sector from an academic and industrial perspective, and that it can become a strong ESA Member state.

Dr. Michaela Musilova is an astrobiologist with a research focus on life in extreme environments (extremophiles). Michaela has a PhD degree from the University of Bristol (UK) and she studied and conducted research at University College London (UK), the California Institute of Technology (USA), Chiba University (Japan) and others. She is also a graduate from the International Space University (ISU)’s Space Studies Program, 2015. Michaela’s astrobiology and space research experience includes: working on astrobiology and planetary protection research projects at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; simulating lunar and planetary surfaces through NASA’s and the UK Space Agency’s MoonLite project; searching for exoplanets at the University of London Observatory; and being an analogue astronaut at the Mars Desert Research Station, USA (2014 & 2017). She has also received numerous prizes and grants, including the Emerging Space Leaders Grant from the International Astronautical Federation (2016); Women in Aerospace – Europe Student & Young Professional Award (2016) and she was selected as one of the most promising 30 under 30 by Forbes Slovakia (2015). Michaela is actively involved in the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, as a patron of the programme in Slovakia and an Emerging Leader Representative for Europe, Mediterranean and Arab states. She is currently the Chair of the Slovak Organisation for Space Activities (SOSA), a visiting professor at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, a lecturer for ISU and the Masaryk University (Czech Republic), and a senior research adviser for Mission Control Space Services Inc.. Michaela also enjoys participating in STEAM outreach activities from teaching at schools, giving public presentations, to working with the media and more, as well as encouraging people to pursue their dreams.

SpaceWatch.Global thanks Michaela Musilova of Slovak Organisation for Space Activities for the interview.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space