As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch Middle East and The Précis, a quarterly space law and policy report produced by Space Law & Policy Solutions, run by the prominent space lawyer and friend of SpaceWatch Middle East, Michael J. Listner, SpaceWatch Middle East is occasionally publishing select articles from The Précis. Reproduced here are Michael’s analysis of Chinas Tiangong-1 situation from a Special Issue XX of The Précis from October 30, 2017. Details of how to subscribe to The Précis are provided at the end of this commentary.

As part of the partnership between SpaceWatch Middle East and The Précis, a quarterly space law and policy report produced by Space Law & Policy Solutions, run by the prominent space lawyer and friend of SpaceWatch Middle East, Michael J. Listner, SpaceWatch Middle East is occasionally publishing select articles from The Précis. Reproduced here are Michael’s analysis of Chinas Tiangong-1 situation from a Special Issue XX of The Précis from October 30, 2017. Details of how to subscribe to The Précis are provided at the end of this commentary.

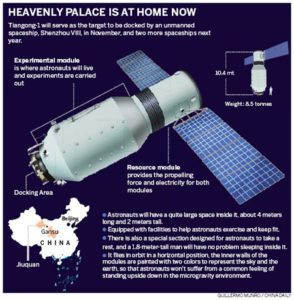

The pending reentry of China’s first large space station, Tiangong-1, is eliciting the usual hyperbole in the media and in some cases making alarmist claims about the threat the station poses. That is not to say the reentry of Tiangong-1 should be taken lightly as with a mass of ~8.5 metric tons, it is the largest space object to reenter the atmosphere uncontrolled since Skylab, which had a mass of ~100 tons and reentered on July 11, 1979. It is uncertain where and when the space lab will reenter and hence whether it will affect populated areas.

Chinese-centric media outlets quote Chinese officials stating the reentry of Tiangong-1 is not concerning; however, Beijing is likely mindful the uncontrolled reentry implicates liability and duties under international law, specifically if any remnants impact the territory of other sovereign states and cause damage. This Special Issue will examine the applicable legal instruments and the international legal obligations that could be implicated by Tiangong-1’s reentry as well as some of the potential legal and political outcomes of the station’s reentry.

Background

Tiangong-1 was launched on September 29, 2011 atop a Long March 2F launch vehicle.[1] The station is 10.4 meters long and has a main diameter of 3.35 meters. It had a liftoff mass of 8,506 Kilograms and provides 15 cubic meters of pressurized volume. The station is designed to accommodate a crew but also hosts a suite of instruments that operate independent of a crew.[2] Tiangong-1 was crewed twice by three taikonauts by Shenzhou-9 in June 2012 and Shenzhou-10 in June 2013. Tiangong-1 ended its service on March 21, 2016 and shortly after China admitted it had lost its telemetry link and the station was orbiting uncontrolled. Tiangong-1 is expected to reenter the atmosphere between October 2017 and April 2018, although a more firm time-frame will likely become available as the station’s orbit further deteriorates.

International Legal Obligations

The fundamental question surrounding Tiangong-1’s reentry is this: What happens if debris from the reentering space station survives and lands in territory of another sovereign nation? Connected to question is what happens if debris lands in the territory of another sovereign nation and causes damage in form or another? Underlying these two questions are two treaties, which China has ratified:[3] the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the Rescue Agreement) and the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the Liability Convention).

The Rescue Agreement

The first set of legal obligations should remnants of Tiangong-1land in the territory of another sovereign state would not rest only with China but with the sovereign state whose territory the vestiges landed. This is borne out in Article 5 of the Rescue Agreement[4], which lists out the following legal obligations for a Contracting Party.[5]

- A Contracting Party that discovers that a space object or its component parts has returned to Earth and landed in its must notify the launching authority and the Secretary-General of the United Nations.[6]

- The Contracting Party shall if requested by the of the launching authority and with their assistance take measures to recover the space object or its component parts.[7]

- Space objects or their component parts found beyond the territorial limits of the launching authority shall be returned to or held at the disposal of representatives of the launching authority. The launching authority must furnish identifying data prior to their return.[8]

- Any space object or its component parts that is believed to be hazardous or have a deleterious nature may notify the launching authority. The launching authority must immediately take steps, under the direction and control of the said Contracting Party, to eliminate possible danger of harm.[9]

- The launching authority must bear the expense incurred by the Contracting Authority under paragraph 2 and 3.[10]

Under the Rescue Agreement, if remnants of Tiangong-1 landed in the territory of a sovereign state, that state would have the responsibility to contact China through diplomatic channels and apprise them there is the likelihood “component parts” of Tiangong-1 have landed in their territory. Conversely, China would be obligated to supply identifying information at which point arrangements would be made to return those “component parts” to China.

The Liability Convention

Another possible player in the reentry of Tiangong-1 is the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects otherwise known as the Liability Convention.[11] The Liability Convention expands upon the principles of liability for damage caused by space objects introduced in Article VII of the Outer Space Treaty.[12] The Liability Convention envisions two scenarios where damage could be caused by a space object. The first scenario envisions a space object that causes damage to the surface of the earth or an aircraft in flight. The second scenario envisions an event where a space object causes damage someplace other than the surface of the earth, i.e. outer space or another celestial body.

It is the first scenario that could implicate Tiangong-1. Article II of the Liability Convention stipulates…

“A launching State shall be absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its space object on the surface of the earth or to aircraft flight.”[13]

Article II creates a strict liability standard where a launching state[14] is considered strictly liable for any damage caused by a space object launched even in the face of circumstances of the damage caused are outside its control. The Liability Convention does not prevent a private citizen of the aggrieved state who was affected or damaged by the space object from seeking redress through the judicial system of the launching state.[15] However, it does prevent redress for the damage caused if a claim is “…being pursued in the courts or administrative tribunals or agencies of a launching State or under another international agreement which is binding on the States concerned.”[16].

What this means is if remnants of Tiangong-1 impact the territory of another sovereign state, China can be held strictly liable for any damages. The key to this; however, is the aggrieved state must present a claim under the Liability Convention through diplomatic channels and it must do within one-year of the occurrence of the damage or the discovery of damage.[17]

There is precedent for claims under Article II of the Liability Convention with the reentry and subsequent crash of Cosmos 954 on January 24, 1978, in the Northwest Territories of Canada.[18] The crash spread radioactive debris from the onboard nuclear reactor that powered Cosmos 954’s radar. The debris from Cosmos 954, which was registered to the then Soviet Union, was located by Canadian authorities and initially identified as coming from Cosmos 954. Canada’s Department of External Affairs issued a diplomatic communiqué invoking Article 5 of the Rescue Agreement, whereby the Canadian government informed the Soviet Union that per its obligation under that Agreement it discovered what it believed to be the remnants of Cosmos 954.[19] The purpose of Canada referencing the Rescue Agreement in this initial communiqué was not only to fulfill its obligations under that accord, but it also likely used it to reinforce that Canada identified the debris as coming from Cosmos 954 and as such belonged to the USSR in advance of its claim under the Liability Convention.

A formal claim against the USSR was made by Canada’s Department of External Affairs via Note FLA-268 on January 23, 1979. FLA-268 cites the legal rationale for Canada’s claim for damages, including its recitation of the Liability Convention. Note FLA-268 was followed on March 15, 1979 with Note FLA-813, which contained the revised costs of the Phase II cleanup of the debris from Cosmos 954 and the text of diplomatic communiqués concerning the incident between the Department of External Affairs and the Embassy of the USSR from February 8, 1978 to May 31, 1978.[20] The Canadian government claimed $6,041,174 (Canadian) but settled for $3,000,000 (Canadian) for the damage caused by Cosmos 954.[21] The Canadian government also reserved the right to be compensated for additional damages that may occur in the future because of the incident, any costs incurred should a claims commission[22] need be established under the Liability Convention and any awards made by the Claims Commission.[23]

Conversely, there is the reentry and scattering of debris from the aforementioned Skylab. The United States assured the international community at the time any debris from Skylab that survived reentry would likely fall in the Indian Ocean. Contrary to that assurance, several pieces of debris fell in the Australian town of Esperance, and authorities in Canberra were alerted. Shortly thereafter, officials from NASA arrived to inspect and collect samples of the debris. The citizens of Esperance were encouraged to bring pieces of debris to the officials for which they were given a commemorative plaque and a model of Skylab.[24] The officials from NASA did not collect all the debris, and in one case a piece of debris was turned over to the San Francisco Examiner, which was offering a $10,000 reward to the first person who could bring a piece of Skylab to the paper’s newsroom.[25] Aside from the plaques and models, there was no official compensation for the debris falling on the town; however, a ticket was issued a year later by the president of the town council against the United States and NASA in particular for littering, which the United States government has yet to pay.6

Otherwise, no formal claim was made by Canberra under the Liability Convention for the incident. One can only speculate as to Canberra’s rationale for not doing so, and it is noteworthy it seems the United States never officially identified the debris as coming from Skylab, and the fact the United States never collected all the debris seems to bear that out. In this instance, it is possible the lack of appreciable damage, politics alone or a combination of these factors figured into Canberra’s decision not to press a formal claim for compensation against a Cold War ally.

The Question of Tiangong-1.

This discussion circles back to the original premise: What happens if debris from the reentering space station survives and lands in territory of another sovereign state? Will the aggrieved state invoke the Rescue Agreement and/or the Liability Convention and will China honor its commitments under these two international treaties? The answer depends on whether any appreciable components reach the surface and whether compensable damage is caused. It also depends on politics and the effect and reach and relationship China might have with the state in question. In other words, China’s soft-power and economic influence over the state in question might be considerable so as to deter the state raising a claim for liability or even formally invoking Article 5 of the Rescue Agreement.

On the other hand, the aggrieved state could file a claim under Article 5 of the Rescue Agreement and make a claim under Article II of the Liability Convention against China through its diplomatic organs. A diplomatic dance would ensue with China either flatly ignoring the Article 5 notification and request or stalling the provision of identifying information to positively identify the components as part of Tiangong-1. This would have the effect of frustrating a potential claim for liability under Article II of the Liability Convention. Equally, China could cooperate with a notification under Article 5 and eventually admit liability for any damage that occurred to bolster its standing in the international community and add credence to the narrative it seeks cooperate with other nations. Surely, the soft-power reaped from such an action would fair outweigh any financial or political embarrassment that might otherwise be had from admitting liability.

There also lies the possibility China could preemptively take steps to recover any components from Tiangong-1 and settle any potential claims for damage before a state invoked Article 5 and Article II of the Rescue Agreement and Liability Convention respectively. Not only would this preempt the need for diplomatic haggling and the political embarrassment of eventually admitting liability, but it would also garner China greater soft-power influence and prestige among not only the state affected but also other states with whom it has relations or wishes to increase its influence to include the United Nations and in particular the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs.[26]

Conclusion

The legal and geopolitical outcome of Tiangong-1 will not play out until the question of when and if remnants of the station impact land within the territory of another sovereign power. It is premature to outright dismiss Tiangong-1 not affecting the surface of the earth as its orbit frequently carries it over many sovereign states, including the continental United States.[27] Until its final plunge from orbit can be better estimated, the media will continue to inquire of experts and hype the story. Subscribers are encouraged to take these reports in the context that the seriousness of the reentry should not be overstated but at the same time not understated. Once the reentry occurs, the following days and weeks will reveal whether there will be any ramifications and whether international space law and geopolitics will find themselves in the mix once more.

[1] Tiangong-1 is identified as NORAD 37820 and its COSPAR identifier is 2011-053A.

[2] See Tiangong 1 Spacecraft Overview, available at http://spaceflight101.com/spacecraft/tiangong-1/ for a general discussion of the specifications of Tiangong-1.

[3] The underlying presumption for the analysis under both the Rescue Agreement and the Liability Convention is all states involved have either ratified, acceded to or otherwise agree to be legally bound to both accords.

[4] Article 5 of the Rescue Agreement harmonizes and builds on Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty with regards to ownership of space objects. See Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. VIII, para. 2, 18 UST 2410, available at https://www.state.gov/t/isn/5181.htm.

[5] “Contracting Party” is not defined in the Rescue Agreement but it does relate to states who have either ratified, acceded to or agreed to be bound by the terms of the Agreement.

[6] See Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space 19 UST 7570, 672 UNTS 119, December 3, 1968, art. 5, para. 1.

[7] See Rescue Agreement, art. 5, para. 2.

[8] See Id. art. 5, para. 3.

[9] See Id. art. 5, para. 4.

[10] See Id. art. 5, para. 5.

[11] Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects 24 UST 2389; 961 UNTS 187, October 9, 1973, available at https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/media/Conv_International_Liab_Damage.pdf.

[12] See Outer Space Treaty art. VII, which states “[e]ach State Party to the Treaty that launches or procures the launching of an object into outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, and each State Party from whose territory or facility an object is launched, is internationally liable for damage to another State Party to the Treaty or to its natural or juridical persons by such object or its component parts on the Earth, in air space or in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies.”

[13] Liability Convention, art. II.

[14] “Launching state” is defined by the Liability Convention in Article I(c).

[15] See Id. at art. XI.

[16] In other words, an aggrieved state cannot seek redress by filing a claim under the Liability Convention if is seeking a remedy through another means. See Id.

[17] See Id., at art. X.

[18] Cosmos 954 (COSPAR ID: 1977-090A) was a Soviet Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite (RORSAT) powered by an on-board nuclear reactor. Its mission was to search for and track Unites States Naval tasks force. See Cosmos 954, National Space Science Data Center, available at http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraftDisplay.do?id=1977-090A.

[19] In its February 8, 1978 communiqué to the Embassy of the USSR, the Department of External Affairs per Article 5(4) of the Rescue Agreement asked the following questions to help it in its search for components of the satellite: 1) What is the nature and amount of fuel? 2) What is the chemical or alloy composition of the fuel? 3) What is the decaying characteristics of the reactor fuel? 4) What shielding was used? 5) Was there any other container which might have provided some protection? 6) If the satellite had come to earth in the Soviet Union what the Soviet authorities have looked for (type of material, energy level and spectrum of ionizing radiation)? Over what size of geographical area would it have been distributed. 7) Is the reactor the same or essentially similar to ‘ROMASKA’ reactor described in IAEA Atomic Energy Review, Vol. 9, Nr. 2, 1971 by Pushkarsky & Okhotik? See 18 I.L.M. 913-915.

[20] See 18 I.L.M. 889, 899, 910-930.

[21] The resulting agreement and compensation actually paid by the Soviet Union is seen more as a punitive measure for Cosmos 954 violating Canadian airspace than a means of compensation for the costs of cleanup and damages under the Liability Convention.

[22] The Liability Conventions allows for the creation of a Claims Commission should the parties not be able to reach agreement on compensation for damages. See Liability Convention art. XIV-XX.

[23] See Protocol on Settlement of Canada’s Claim for Damages Caused by “Cosmos 954,” Apr. 2, 1981, Can.-U.S.S.R., 20 I.L.M. 689 (1981) and available at http://www.spacelaw.olemiss.edu/library/space/International_Agreements/Bilateral/1981%20Canada-%20USSR%20Cosmos%20954.pdf.

[24] Stewart Taggert, “The Day Skylab Fell”, Wired, March 22, 2001, available at https://www.wired.com/2001/03/the-day-the-skylab-fell/.

[25] See Id.

[26] China’s influence with the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs appears to be considerable as evidenced notably by the Office removing China’s first notification to the Registry of Space Objects about the pending reentry of Tiangong-1 for no other explanation than “technical reasons” before reinstating it almost two months later. Also, the Director of UNOOSA during an interview implicitly endorsed China’s Belt and Road initiative despite the fact China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, which are contrary to UNCLOS, encompass that initiative. (Note: It appears all Chinese media links referencing the Director’s comments are no longer available, which garners scrutiny in of itself).

[27] NY20.com has a rudimentary tracking tool that displays the track of over 18,000 objects in orbit, including Tiangong-1, which can be found here: http://www.n2yo.com/satellite/?s=37820/

Disclaimer

The Précis is a product of Space Law & Policy Solutions. Opinion, commentary and analysis contained in The Précis is for informational purposes. The Précis is not legal advice nor is it a substitute for legal advice. Subscription to The Précis does not create an attorney/client relationship nor is information contained within protected by attorney/client privilege. The Précis may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including but not limited to photocopying, edits, website uploads or other electronic or mechanical methods, except for quotations with proper citation, without the express permission of the author.

SpaceWatch Middle East thanks Michael J. Listner for permission to republish his work.

To subscribe to The Précis please visit: http://www.spacelawsolutions.com/the-pr-cis-.html

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space