The passage of the UK Space Industry Act 2018 into law has not, as yet, seen any further developments, however crucial questions in relation to liability, insurance and charging still need to be addressed. There has been a call for evidence to inform on these crucial regulatory aspects and once these questions are addressed, then there will be something of a clearer picture as to the regulatory environment of UK Space Activity.

The first question that needs to be addressed is that of liability. In line with the obligations under the Outer Space Treaty 1967 and the Liability Convention of 1972, s36 of the 2018 Act places a liability on an operator carrying on spaceflight activities to indemnify the Government against any claims brought against them for loss or damage caused by those activities. In section 12(2) of the 2018 Act there is provision for specifying a limit on an operator’s liability to indemnify the UK Government against claims in respect of damage or loss. S.34(5) allows for regulations to limit the amount of liability of an operator in respect of injury or damage to third parties. The UK Space Agency, when licensing under the Outer Space Act 1986 (OSA), currently limits liability for claims against Government to €60 million for standard missions launching overseas.

The consultation seeks to establish whether this is an appropriate limit for activities under the Space Industry Act. The consultation goes further and points to the provision within Schedule 1, Para 36, which allows for the inclusion of conditions within licences issued under the Act that could mandate the use in contracts of cross waivers of liability for injury or damage from carrying out the licensed activities. This could mean that all parties involved in a spaceflight activity would have to bear their own losses. The various options in respect of liability have been included in the consultation and a crucial for engendering confidence within the UK space sector.

The next area requiring further regulatory activity is that of insurance. Currently under the OSA a licensee is required to demonstrate that they hold third party liability insurance for the activities licensed under that Act before a licence is issued. These activities are where a UK entity procures a launch (purchases space on a launch vehicle for its satellite) and the in-orbit operation of a satellite. The requirement to obtain third party liability insurance for these activities carried out under both the OSA and the SIA will continue. Accordingly, s 38(1) provides for the introduction of regulations to require holders of licenses granted under the 2018 Act to obtain insurance in respect of specified risks and liabilities. The scope of the activities and the resulting insurance requirements is one of the key questions that needs to be addressed by the consultation. One of the most persistent criticisms levelled against UK space regulation is the availability and expense of third-party liability for UK launch. The call for evidence will also seek views on the ways this can be ameliorated whilst still putting in place appropriate securities and financial protection.

The final area of the consultation is on the cost to operators of any regulatory regime. Whilst the operators will, predictably, want this cost to be as low as possible, the regulatory process will still incur expense and, rather than this being borne by the UK taxpayer, an appropriately fair and equitable process needs to be determined. S.62 of the 2018 Act allows this to be determined by regulations and so the consultation process will feed into the creation of those regulations.

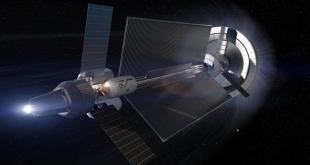

Aside from this consultation, the underlying purpose of the Space Industry Act is to provide the regulatory conditions for launches from the UK. To further this aim, the UK government has announced a package of grants designed, primarily to encourage established companies such as Lockheed Martin provide much needed technological and engineering know-how for UK launch efforts. A £2.5million grant was made to the Highlands and Islands Enterprise Agency to develop a spaceport in the A’Mhonie peninsula in Sutherland, Scotland. The UK government has also said Lockheed Martin would establish the launch operations in Scotland and develop “innovative technologies” with support from two UK Space Agency grants totaling £23.5 million. A further £2 million development fund for horizontal launch sites around the UK has also been announced.

What these grants say about UK space ambitions is an intriguing mixture of messages. First, any additional expenditure on space is welcome. This is recognition from the UK government that investment is space is needed to keep pace with the global space market. What it does show, however, is that government largess in this area is not limitless. A grant of £30million to develop the infrastructure for a spaceport does not, in the grand scheme of things, represent much of an investment. The government is, instead, hoping private investment will do much of the financial heavy lifting in respect of the spaceport infrastructure.

The UK political situation is still in a position of gridlock due to the difficulties in securing a transitional arrangement for leaving the European Union. This means that any significant policy or legislative arrangements must always be viewed through the lens of Brexit. This is as true of space activity as of any other area of government. The granting of £30 million for the development of space ports is dwarfed by the £100 million that has been set aside for exploring the prospect of developing a sovereign GNSS system to replace the UK involvement in the EU-led Galileo project. Politically, the provision of an independent, secure GNSS has become something of a totem for a government encountering significant difficulties in negotiating an appropriate settlement with the EU. Whether this pilot study will conclude that a sovereign GNSS is either affordable or practical is open for discussion. One thing is certain. Any commitment by the UK government to such a project must be treated with caution. The UK government does not have a particularly good track record at developing large infrastructure projects and it will be interesting to see if this will prove to be an exception.

Dr. Christopher Newman is Professor of Space Law and Policy at Northumbria University in the United Kingdom. The views expressed here are those of Dr. Newman and do not necessarily reflect the views of Northumbria University.

This analysis originally appeared in The Précis, Issue XXVII, 3rd Quarter 2018, pp. 25-27, and is gratefully republished here with the permission of its publisher, Michael J. Listner.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space