by Michelle Hanlon of For All Moonkind

For All Moonkind is a young organization already having considerable impact on the discussion about how we preserve our heritage in space. Just recently, it was named one of the most innovative companies in space by Fast50. The mission behind what this group of lawyers, scientists, archaeologists, communications executives and policymakers is trying to achieve seems simple: “Ensure the six Apollo Lunar Landing and similar sites in outer space are recognized for their outstanding value to humanity and consequently preserved and protected for posterity as part of our common human heritage.” However, there are many hurdles to clear, as Michelle Hanlon, Space Lawyer and Co-Founder of For All Moonkind, explains.

For All Moonkind is a young organization already having considerable impact on the discussion about how we preserve our heritage in space. Just recently, it was named one of the most innovative companies in space by Fast50. The mission behind what this group of lawyers, scientists, archaeologists, communications executives and policymakers is trying to achieve seems simple: “Ensure the six Apollo Lunar Landing and similar sites in outer space are recognized for their outstanding value to humanity and consequently preserved and protected for posterity as part of our common human heritage.” However, there are many hurdles to clear, as Michelle Hanlon, Space Lawyer and Co-Founder of For All Moonkind, explains.

It was described as an agonising dilemma. In April 1959, the Egyptian Minister of Culture contacted the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Egypt needed help. In order to promote and accelerate its industrialisation and the modernisation of its economy, it needed to harness the power of the Nile River. Unfortunately, the plan to build what is now known as the Aswan High Dam would result in the creation of a vast lake. A lake which would assure the obliteration of 3,000 year-old temples and monuments – footprints of an ancient civilisation known as Nubia. In October of that same year, the Sudan sent a similar plea to UNESCO. Neither country had the money or the capability to protect these historic sites.

The response was swift. UNESCO spearheaded a global international effort to rescue the Nubian heritage that its Director- General knew humanity could not afford to lose.

It became the greatest archaeological rescue operation of all time. Even as humans waged a bitterly Cold War, raced to the Moon and fought for civil rights, the call to preserve our history was not ignored. More than US$80 million was raised from 50 UNESCO-member nations and a number of private entities from around the globe. International panels of experts from five continents convened to develop and then implement strategies to save 22 temples and architectural complexes – some of them relocated brick by brick. In short, the international community came together to save treasures they recognised belonged, not just to Egypt or the Sudan, but to humanity as a whole. In the words of UNESCO Director-General Amadou-Mahter M’Bow, the International Rescue Nubia Campaign “will be numbered among the few major attempts made in our lifetime by the nations to assume their common responsibility towards the past so as to move forward in a spirit of brotherhood towards the future.”

And it didn’t end there. Other campaigns to save monuments of universal value followed including, among others, Venice and its Lagoon in Italy, the Archaeological Ruins of Moenjodaro in Pakistan and the Borobodur Temple Compounds in Indonesia. More important, the Nubia Campaign created the foundation for an international convention on world heritage – a convention that builds and strengthens what the Honorable Russell E. Train, who has been called the “father of World Heritage,” identified as “a sense of kinship with one another as part of a single, global community.”

The World Heritage Convention has been a tremendous success, with 193 member States. That’s 193 nations who understand we need to preserve our history and our humanity so that we may learn from past mistakes, build upon past success, and, most importantly, recognise our human unity.

As humankind stretches its reach into space, we must assure these values accompany our technology. Our future depends on it. We submit that now is the Nubia moment for human heritage in outer space.

The parallels are intuitive.

Humans – including, no doubt, the ancient Nubians – have marveled at the heavens for centuries. The first human object to break the bonds and circle the Earth was Sputnik, launched on October 4, 1957. And the first human incursion on the Moon came in the form of Luna 2, which made a hard lunar landing in 1959. It took another ten years and many robots before Neil Armstrong placed humanity’s first off-world footprint in the jagged and sharp dust that covers the Moon’s surface. Those first human steps were made by one, but for all (hu)mankind.

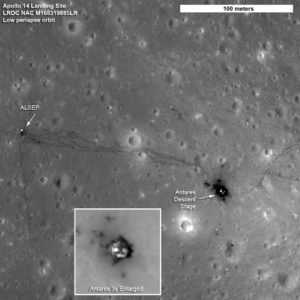

Like the Nubian heritage sites, the first landing sites on the Moon are treasures that are universally significant and valuable. These were humanity’s first steps off our Earth. They represent the dawn of our evolution into a space-faring species. They could even be considered the cradle of a soon-to-come Moon community. The sites memorialise achievements unparalleled in history; built on the backs of centuries of science from all corners of the world.

What’s more, the landing sites, the crewed Apollo sites as well as the robotic sites that preceded and followed, are an archaeologist’s dream. They extend and confirm humans as an exploratory, migratory species. They are the first archaeological sites with human activity that are not on Earth, and they bear witness to some of the most important technological developments in human history. Moreover, they are frozen in time, preserved by the vacuum of space – and by the fact that no human, and only a handful of rovers, has returned to the Moon since 1972.

Thankfully, that’s about to change. Just as the waters were headed to the Nubian sites, humans are headed back to the Moon. While a working human outpost on the Moon may be decades away, a number of countries and private companies, like PTScientists and Astrobotic, plan to send robots to the Moon as early as 2018 and humans as early as 2030. Of course, unlike the Aswan High Dam project which could not help but flood the Nubian sites, there is no deliberate intent to bring harm to any of the historic sites on the Moon. Nevertheless, we cannot allow a perceived lack of urgency to lull us into complacency. We can no longer afford to ignore the fact that no enforceable laws exist to prevent or even inhibit defilement or vandalism. Even the most well-intended visitors may be unaware of the damage they are doing while roaming near a site. What’s worse are those who would take a “piece of history” for themselves. And worse still, those who would plunder simply for profit.

The challenge of the Nubia campaign was fixed and concrete. The international community had a finite period of time in which to unite in solidarity to protect and safeguard treasures humanity must cherish. Funds and minds had to meet, agree and employ Herculean efforts to move heritage landmarks.

In one significant way, the challenge of this new Nubia moment is decidedly simpler: no monuments need to be moved. We stand at an incredibly unique threshold in human evolution. We have the opportunity to recognise these sites of universal value and balance their preservation against the development, exploration and exploitation of the Moon and its resources before anything threatens them.

Of course, the path to preservation, whether for history or science is complicated. The UNESCO World Heritage Convention does not apply to these sites as they are not contained within any sovereign nation – indeed, the Outer Space Treaty explicitly prohibits the national appropriation of outer space, the Moon or any celestial bodies. Some detailed technical guidelines were promulgated by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration, but these are voluntary and pertain only to US sites.

The space treaties themselves are silent with respect to heritage. Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty speaks to ownership of objects, but is silent with respect to the sites themselves. Thus, items left in space remain under the jurisdiction and control of the nation responsible for putting them there. Article IX of that treaty requires all activities in outer space be conducted with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties,” which, arguably, suggests that States should not interfere with or otherwise despoil the objects of another. But what is “due regard” and what is a “corresponding interest?” The Liability Convention imposes fault-based liability on a State Party that damages the space object of another State. But how do you quantify damage to an artefact? Article V of the Return and Rescue Agreement is clear that any object removed from the Moon must be returned to the State of origin. But the research value of the landing sites requires that the objects within their bounds be observed and scrutinised in situ. Which raises a whole different slew of issues. Leaving the objects in situ essentially results in perpetual occupation of the surface upon which they rest. This runs afoul of the principle of non-appropriation encapsulated in Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. Thus, leaving the lunar landing sites untouched gives rise to the appearance that those sites belong to the United States, Russia, China or India, as the case may be.

They do not. They are the universal heritage of all humankind and should be celebrated and preserved accordingly. It is time to rise up to our own Nubia moment and fill the gaps in our international laws to assure the protection of these and future sites. International consensus on space history preservation will offer the added benefit of setting a needed global tone for future space exploration. Because, as the Honorable Russel Train recognised:

“World Heritage [is] something more than simply helping to assure protection and quality management for unique natural and cultural sites around the world –as critically important as that goal is. Above and beyond that goal, I see the programme as an opportunity to convey the idea of a common heritage among nations and peoples everywhere! I see it as a compelling idea that can help unite people rather than divide them. I see it as an idea that can help build a sense of community among people throughout the world. I see it as an idea whose time has truly come.”

For precisely these reasons, we, at For All Moonkind submit that the time to recognise universal heritage in outer space has come. We are an entirely volunteer not-for-profit organisation made up of lawyers, scientists, archaeologists, communications executives and policymakers from around the world. We are the only organisation in existence that is committed to developing the programmes necessary to manage the preservation of human heritage in outer space. In addition to raising awareness, our team is focused on developing a programme much like the World Heritage programme that allows for the identification and study or preservation of heritage sites while suitably addressing the unique issues left open by the Outer Space Treaty and its progeny.

For precisely these reasons, we, at For All Moonkind submit that the time to recognise universal heritage in outer space has come. We are an entirely volunteer not-for-profit organisation made up of lawyers, scientists, archaeologists, communications executives and policymakers from around the world. We are the only organisation in existence that is committed to developing the programmes necessary to manage the preservation of human heritage in outer space. In addition to raising awareness, our team is focused on developing a programme much like the World Heritage programme that allows for the identification and study or preservation of heritage sites while suitably addressing the unique issues left open by the Outer Space Treaty and its progeny.

As a direct result of our efforts thus far, the Draft Resolution on Space as a Driver of Sustainable Development considered by the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Scientific and Technical Subcommittee in February 2018 recommended the creation of “a universal space heritage sites programme . . . with a specific focus on sites of special relevance on the Moon and other celestial bodies.”

Unfortunately, the subcommittee meeting concluded without agreement on this matter. While perhaps understandable given the administrative and political framework of the United Nations, it is nevertheless unacceptable to leave our heritage in limbo. The fact is, our Nubia moment has arrived and our campaign For All Moonkind begins. And it is a campaign for Moonkind because this effort to preserve our history truly is for the benefit of our future, a future we are confident will include the expansion of our civilisation into space, starting with the Moon. Our Moonkind descendants will thank us for preserving the cradle of their community, the first footsteps of their forbears.

The UNESCO website proclaims that the Nubia Campaign “was a defining example of international solidarity when countries understood the universal nature of heritage and the universal importance of its conservation.”

We ask you to join us in solidarity and support our efforts to fill the gaps in our laws and develop a program the will effectively balance development and heritage preservation – without the need for a US$80 million rescue effort.

Learn more at www.forallmoonkind.org.

Michelle Hanlon is a space lawyer. She is a Co-Founder of For All Moonkind, Inc. and a founding partner of ABH Aerospace, LLC. She earned her J.D. magna cum laude from the Georgetown University Law Center and her B.A. in Political Science from Yale College.

Michelle has more than twenty-five years of corporate transaction experience. She earned her LL.M. in Air and Space Law from McGill University where the focus of her research was on commercial space and the intersection of commerce and public law.

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space

SpaceWatch.Global An independent perspective on space